Here's a pop quiz: Name one link between sedimentary rock, oil exploration, and potential indicators of extraterrestrial life. You guessed it—microbes.

If that one slipped past you, don't worry. It eluded scientists for years until researchers from the University of Illinois determined that microbes increase the growth rate of calcium carbonate, a widely used, ever-forming chemical compound that takes the form of chalk, limestone, marble, and other sedimentary rock composing about 4 percent of Earth's crust.

The discovery has stirred interest, as calcium carbonate growth has long been largely considered an inorganic process. Bruce Fouke, however, a professor of geology and molecular and cellular biology at the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, discovered that microbes more than double the ubiquitous compound's formation rate.

"This for the first time identifies calcium carbonate 'growth rate' as a result of microbial control," Fouke says. He adds that growth rate affects the shape and chemistry.

Fouke's research team spent a decade studying calcium carbonate formation in coral reefs and hot springs, but he says this discovery makes possible new quantitative, useful models of its growth.

For example, researchers can better predict the effect of global climate change on coral (formed from calcium carbonate), or better estimate the future shape of underground oil, gas, and drinking water supplies, which can be affected by calcium carbonate growth.

Because researchers can recognize the work of microbes in calcium carbonate, they can also examine rocks from other planets and judge whether they were affected by life, Fouke says.

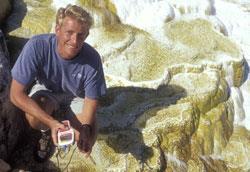

Fouke conducted experiments at Yellowstone National Park's Mammoth Hot Springs, an ideal spot. The park's travertine terraces, composed of calcium carbonate, grow five millimeters a day in the microbe-filled water. Ocean coral, by contrast, grows about one millimeter per year.

Fouke's research team filtered microbes from the water. The compound grew 2 ½ times faster with microbes in the water.

To determine why, Fouke is working with colleagues in chemistry, microbiology, animal sciences, mathematics and other fields. He's working with a proteomics expert at the U of I to identify microbial proteins that could reduce the energy required for calcium carbonate growth.

Fouke's discovery "expands the linkage between microbiology, geochemistry, and geology," Gill Geesey, a microbiologist at Montana State University, told ScienceNOW Daily News.

Calcium carbonate forms so abundantly that it provides a natural history of the planet by leaving a "chemical fingerprint" of past animals, plants, and bacteria, Fouke says. It forms key oil and gas reservoirs (as limestone), and the compound is also used as building materials, medical supplements, tints in glass, and antacids. It's also used in paper, plastic, paint, adhesives, lime, and animal feed, and can be found in numerous grocery items such as toothpaste and dough.