With the presidential campaign coming down to its final weeks, the national political environment is more tightly contested than it has been since the 1880s, according to a political science professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

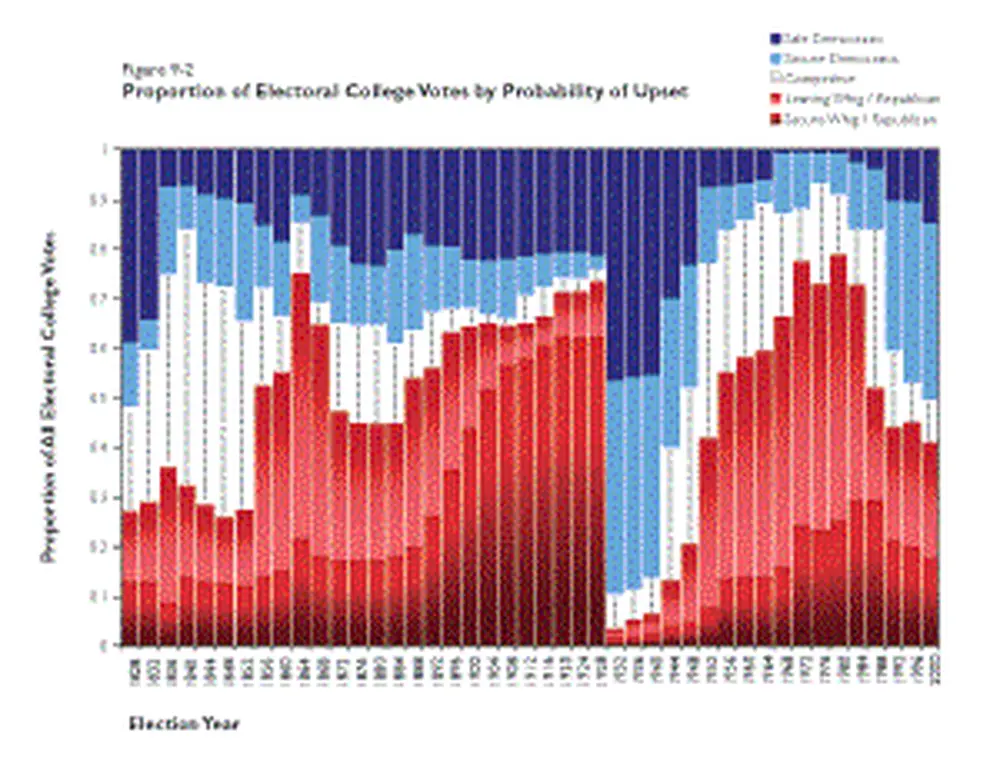

For the past few campaigns, Democratic and Republican parties have fought tight presidential races over an electoral map evenly divided between states that are considered either securely in their column or leaning their way. In the middle sits a relatively small number of battleground states—such as Ohio and Florida in today’s races—that could go either way.

Peter Nardulli, director and founder of the Cline Center for Democracy, spent 20 years studying electoral archives down to the county level and concluded the nation hasn’t been this equally divided over its political views since the days of Grover Cleveland. The electoral maps of most of the 20th century, he reveals, have either favored Democrats, as during the Great Depression and World War II, or Republicans, as during the 1960s and 1970s.

The difference between today and the 1880s, he says, is that in the 1880s party loyalties were stronger and parties were more decentralized. Ward heelers effectively doled out favors and patronage on the local level in return for votes. Today the election-to-election vote fluctuations are bigger—in other words, there are more swing voters.

“A lot of people [in the 1880s] never changed their votes throughout their entire life,” Nardulli says. “Today there’s more variability in voting.”

It creates an intense political environment where neither party can feel comfortable, he adds.

“They really have to concentrate on activating their bases and getting them out to vote, and that’s why you see so much concern particularly with the Republicans, because [John] McCain has not had a particularly good relationship with the Republican base,” Nardulli says. “So [Sarah] Palin comes in and she energizes the base, and she has to, because McCain has almost no margin of error.”

He feels that, in the absence of an incumbent, the deciding factor in this election will be constituents’ party loyalties and evaluations of how well the parties have performed. Even in such a tight environment, a landslide is still possible, Nardulli says.

“I think you’re looking at a really tight election that McCain wins, or a big Obama win, at least in the electoral college,” he says. “He may not win much more than 54 or 55 percent of the vote, but he could get 320, 340 electoral votes just by squeaking out wins in places like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida.”