A giant tarantula, the size of a house, has been unleashed on an unsuspecting desert community, the result of an experiment gone awry. Researchers are trying to figure out how to stop the rampaging arthropod when the female scientist suddenly blurts out what May Berenbaum describes as one of the most cringe-inducing lines in cinematic history: “Science is science, but a girl’s got to get her hair done.”

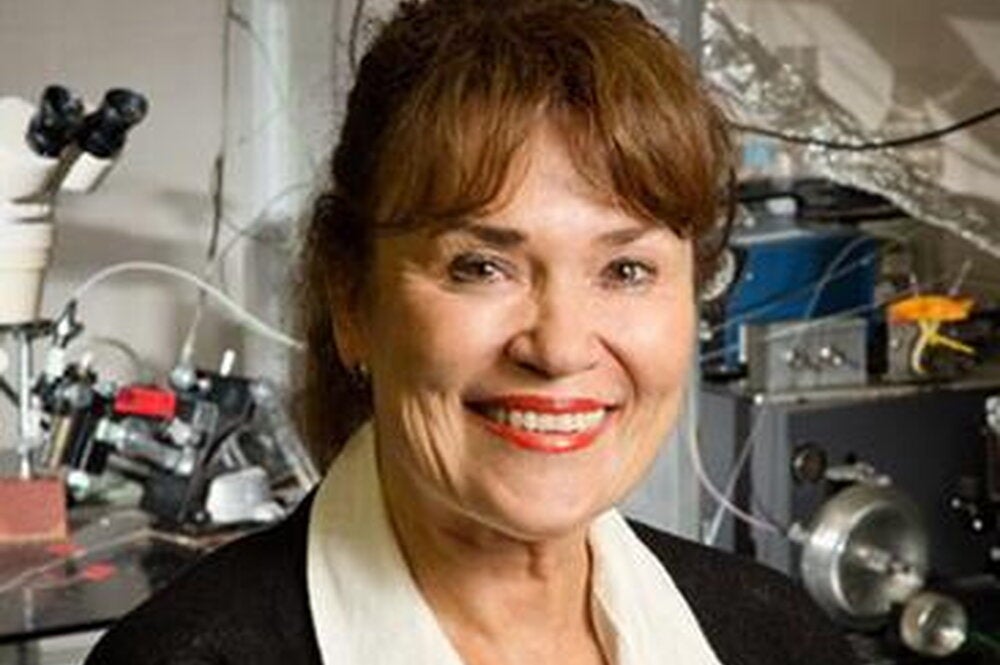

That line, from the 1955 movie Tarantula, “was a low point in the depiction of female scientists,” says Berenbaum, head of the LAS Department of Entomology. It was also one of several scenes selected by Berenbaum when she compiled some of the worst science movie moments in preparation for the kick-off symposium for the Science and Entertainment Exchange.

Berenbaum is on the steering committee of the National Academy of Sciences’ new Science and Entertainment Exchange, which opened an office in Los Angeles last November in an attempt to connect movie and television professionals with top scientists in the world. Jerry Zucker, director of such classic comedies as Airplane!, is vice-chair of the committee and a driving force behind the effort, along with his wife, Janet.

“The National Academy of Sciences has been trying to figure out a way to connect to Hollywood because movies and TV have a profound effect on American attitudes and American values. It’s an amazingly powerful industry for social and cultural transformation,” says Berenbaum, who spearheads the Insect Fear Film Festival, held annually on the University of Illinois campus for 25 years and counting.

Berenbaum and fellow U of I entomologist Gene Robinson were both involved with last fall’s symposium, which introduced the Science and Entertainment Exchange and drew a host of big names from entertainment and the sciences. Among them were director/writer Lawrence Kasdan, who wrote the screenplays for The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark; Nicholas Meyer, director of numerous hit movies, including Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan; and Steve Chu, President Obama’s choice for Secretary of Energy.

Seth McFarlane, creator of the hit cartoon Family Guy, hosted the event, which Berenbaum says turned out to be “one of the hottest tickets in Hollywood. It shocked the organizers. They thought the room would be half-empty.” But as it turned out, she says, a lot of people in Hollywood are “closet science nerds.”

The Science and Entertainment Exchange has been set up to make introductions, schedule briefings, and arrange for consultations with scientists for anyone developing science-based entertainment content. The goal is to help writers, directors, and producers grapple with science, but not to tell Hollywood how to make movies, Berenbaum says.

“That’s what they’re good at,” she explains. “The idea is to make information available so it can be used in different, more creative ways.”

As a scientist who keeps her finger on the pulse of popular culture, Berenbaum has been involved for a long time with efforts by the National Academy of Sciences to reach out to entertainment. As she puts it, “I’m glad all those hours in front of the television haven’t been wasted.”

Berenbaum says the increasing presence of science in entertainment, particularly on television, is heartening. One of the best examples is CSI, in which investigators use scientific methods to solve mysteries. However, she says she is heartbroken that the Gil Grissom character—a heroic entomologist with a stable of racing Madagascar cockroaches—is leaving the show.

Among the show’s strong points, she says, is that CSI depicts scientists working together, contrary to the classic movie stereotype of “a scientist as some guy sitting alone in a laboratory. The whole modern scientific enterprise rests on collaboration, interaction, and engagement with other scientists.”

CSI is also thorough with its science. For instance, Berenbaum was once contacted by a CSI fact-checker who was trying to find out if gunshot residues could be detected on maggots. (They can.) “CSI has done a brilliant job with its recurring emphasis on interpreting the evidence and not going beyond the evidence,” she adds. “It’s well acted and well scripted, and they do their homework in depicting the science.”

The Science and Entertainment Exchange will make that homework a little bit easier.