A promising new stem cell study on mice has researchers at the University of Illinois hopeful that they have turned an important corner in the battle against Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

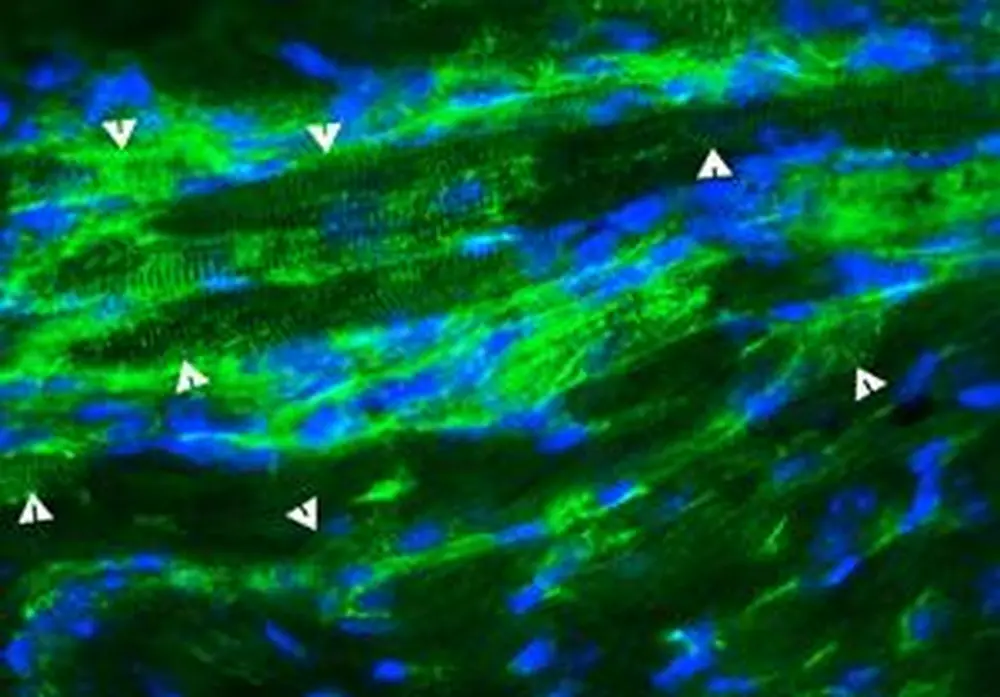

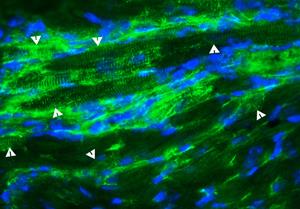

Researchers transplanted stem cells derived from normal mouse blood vessels into the hearts of mice afflicted with the genetic disorder. They found that the treatment prevented or delayed heart problems in mice that did not already show signs of the structural and functional defects associated with DMD, according to Suzanne Berry-Miller, professor of comparative biosciences and Neuroscience Program research affiliate.

DMD is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene for dystrophin, a protein that anchors muscle cells in place when they contract. Without dystrophin, muscle contractions tear cell membranes, leading to cell death.

“This is the only study so far where a functional benefit has been observed from stem cells in the dystrophin-deficient heart, or where endogenous stem cells in the heart have been observed to produce new muscle cells to replace those lost in DMD,” Berry-Miller says. “So I think it opens up a new area to focus on in pre-clinical studies for DMD.”

DMD is the most common muscular dystrophy, with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating that it affects one in every 3,500 males. The disease is more prevalent in males because the dystrophin mutation occurs on the X chromosome; males have one X and one Y chromosome, so a male with this mutation will have DMD, while females have two X chromosomes and must have the mutation on both of them to have the disease.

Females with the mutation in one X chromosome sometimes develop muscle weakness and heart problems as well, and may pass the mutation on to their children.

Although medical advances have extended the lifespans of DMD patients from their teens or 20s into their early 30s, disease-related damage to the heart and diaphragm still limits their lifespan. Drugs are able to prolong heart function, but they can’t yet replace lost or damaged cells.

Almost 100 percent of patients develop dilated cardiomyopathy, Berry-Miller says, in which a weakened heart cannot pump blood properly throughout the body.

Berry-Miller and her colleagues do not yet fully understand how the stem cell treatment delayed the onset of cardiomyopathy. They observed that some of the injected stem cells became new, healthy heart cells. The treatment also caused existing stem cells in the heart to divide and become new heart muscle cells, stimulating new blood vessels.

Their findings appear in the journal Stem Cells Translational Medicine. The Illinois Regenerative Medicine Institute supported the research.