What can emblems created hundreds of years ago tell us about how human society evolved? Quite a bit, actually—so much so that a small, energetic undergraduate student research project in the College of LAS focused on making emblems easier to study is drawing attention to not only the subject matter itself but how students can learn and help the study of humanities evolve.

In addition to the students’ contributions to the growing Emblematica Online project, which was initiated at U of I, they’ve developed their own abilities in the developing area of Digital Humanities, where the application of computing skills and dataanalysis to Renaissance texts and images are revealing new knowledge about our past.

Emblematica Online is a federally funded collaboration between the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, the University Library, and several other institutions in the U.S. and Europe to digitize, index, and build a new portal for rare and fragile emblem book collections in English, Latin, and the European languages. The University Library houses one of the world’s largestand most important Renaissance emblem book collections.

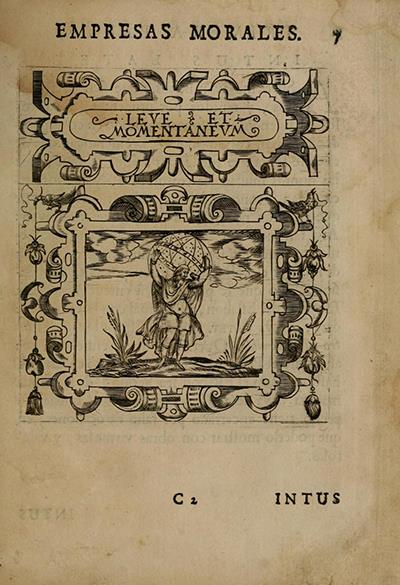

Emblem books were common in the Renaissance, consisting of mottos, images, and texts that scholars say reveal much about past culture and history. In two separate multi-year grant cycles, the National Endowment for the Humanities granted Emblematica Online the highest awards in its grant category for the study of emblems.

With funding from the School for Literature, Cultures, and Linguistics at U of I, Mara Wade, professor of German and principalinvestigator for Emblematica Online, established the Emblem Scholars program to teach students the craft of working with old and fragile books, as well as help advance Emblematica Online’s project goals.

Not only have the students learned much about languages and the historical period from about 1500 to 1750, but they’ve also learned how to make historical texts and images more accessible through indexing, how to digitize rare books, and how to work as a research team, among many other lessons that are increasingly vital to the humanities. They have transcribed all the mottos in almost a dozen books since the project began.

The Emblem Scholars have created a website of the scholarly research.

Heidi Heim, a senior majoring in art history with a minor in French, says the undergraduates have learned an “absurd” amount of skills during the past couple years, including, for her, transcribing data into spreadsheets, using the Arkyves (a popular database of historical images and texts) for learning Iconclass, a classification system for art, photographs, illustrations, and other images—including emblems—used by museums and other institutions around the world.

“In our learning assessments, we discussed what we learned with the class, and also how we’ve grown as individuals and students,” Heim says. “And this class—it’s not even a class to me anymore. It’s a huge thing within itself—it’s my research now.”

Wade, who advises the undergraduate researchers, says working with the students has been a rewarding experience.

“Initially I was skeptical about how I could possibly involve undergraduate researchers in a project that really requires a lot of knowledge of foreign languages, and especially archaic forms of the language,” she says. “But obviously, it has been so successful, and we will be very sad when they start graduating.”

The undergraduates’ numbers have already been trimmed a bit by graduation, and the group now includes Heim; Trish Fleming, a junior majoring in English; and Melina Zavala, a junior double majoring in psychology and English. As Wade describes it, they have served on the project longer than expected thanks to their own determination.

“We started off with six students in the first semester. I was hoping to get two or three, but 25 students were interested in it,” Wade says. “And then after the first semester was done, these three came back and kicked down my door and said, ‘We want to do this some more, will you please work with us?’ I hadn’t planned on doing it anymore...but I just couldn’t say no, and that’s how this keeps going.”

Their role as Emblem Scholars—and the work they’ve done for the project—has been intriguing to other researchers and scholars. Wade describes the interest at a Sixteenth Century Studies Conference 2014, where a presentation about the undergraduates’ research by Johannes Fröhlich, a graduate student in Germanic Languages and Literatures who assists the undergraduates, drew wide attention.

“Johannes presented a poster on the undergraduate research experience with Emblematica Online,” Wade says. “There was a line in front of that poster, and the poster session was supposed to be a couple hours, but he and I were there for about four hours, answering questions primarily about the undergraduate research experience.”

The students say the experience has been meaningful on several levels. Fleming’s role with Emblematica Online helped her gain acceptance in 2014 to the prestigious Andrew W. Mellon Summer Academy and Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship Program, at the Art Institute in Chicago, where she was so successful that the program contacted Wade and asked her to encourage more U of I students toapply.

Fleming describes how, once the books of emblems are scanned, the students prepare spreadsheets which members of the scholarlyresearch team then convert to digitally attach images to mottos—a process called stitching—ultimately to make them accessible and searchable online.

“We transcribe the motto in whatever language it is, because we all have experience working in different languages,” she says. “I’m studying Latin, and we can call help each other when I don’t know how to transcribe something in Spanish or French.”

Zavala wants to develop a career focused on the digitization of art, the archival process, and the restoration of books. She says that through her work with Emblematica Online, and with her background in psychology, she sees that the Renaissance still has relevancetoday. She wrote a research paper about the Emblemas Morales, a book of emblems by Sebastian De Covarrubias from the 17th century.

“It showed how he thought as a priest, and how it reflected how society as a whole thought of moral issues,” Zavala says. “This can also be applied to see how we have changed, and how the reflection of that type of thinking still exists or doesn’t exist anymore. Are we changing or not? It can be brought back to the modern day.”