They were called “the Romans of the New World.” The Iroquois, a league of five (and later six) Native American nations in what is now upstate New York and southern Ontario and Quebec, were sometimes compared to Romans because of the scope of their influence and power. European writers from the 17th to the 19th centuries also compared Iroquoian and other Native American languages to Latin and Greek.

When Craig Williams learned of these comparisons, his interest was piqued because this University of Illinois classics professor specializes in ancient Roman culture and the Latin language. He also happens to be of Mohawk descent with three Native American great-grandparents (the Mohawks are one of the Iroquois nations). What’s more, two years ago he was ceremonially adopted as a child of the bear clan among the Zuni people of New Mexico.

Williams says that, as far as he knows, his ancestors never lived on a reservation, and over the generations his family lost touch with their Native American cultural heritage; but he adds that, as in many families like his, a process of reconnecting has begun.

Intrigued by the comparisons with ancient Rome, Williams began to explore the meeting point between Native American cultures and the ancient cultures of Rome and Greece. That’s when two U of I professors—Robert Warrior of the American Indian Studies Program and Robert Parker in the Department of English—led him to the Latin and Greek writings of three Indian students at Harvard.

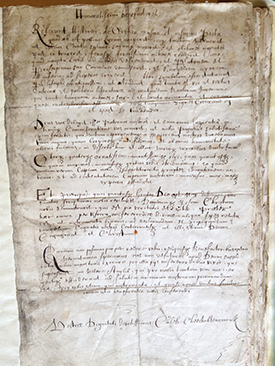

One of these students was the fascinating figure of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American to graduate from what was then called Harvard College. Cheeshahteaumuck, from the Wampanoag tribe, graduated from Harvard in 1665, and his portrait was put up on campus in 2010. Cheeshahteaumuck left behind only one piece of writing—a letter written in Latin—but it has become a starting point for Craig Williams’ research project on the encounters of Native Americans with classical European culture.

Williams sees the Cheeshahteaumuck letter as a type of “edge of the woods” encounter. The edge of the woods was neutral ground between the forest and the clearings where the Iroquois built their villages. At this edge—neutral territory—the Iroquois would conduct ceremonies introducing diplomatic encounters with Native Americans from other villages and later with European settler-colonists.

Cheeshahteaumuck wrote the letter to his English benefactors in Latin, which is also a kind of neutral ground, Williams says—like the edge of the woods.

“The edge of the woods is not the woods, and it’s not the village,” he says. Similarly, the Latin language is a kind of middle ground because it is not a Native American language, but it is also no longer a living European language. “Latin is nobody’s native language,” he points out.

“I think of this research project as a journey, and I’m not yet clear where I’ll end up,” adds Williams, who is fascinated by what those in his field call “the reception of classics”—how knowledge about ancient Rome and Greece and their languages are received and used by later cultures.

Another story that caught his attention is that of Eunice Williams, the daughter of a Protestant minister who was captured in a raid on a Massachusetts village in 1704 and taken to a Mohawk village in Canada, across the St. Lawrence River near Montreal. She was seven years old when she was captured, but as a grown woman she chose to remain in the village, where she was given a Mohawk name and married a Mohawk man.

This particular Mohawk village was Roman Catholic, so Eunice Williams converted to Catholicism and wrote to her father in English about reciting Latin prayers in a Mohawk community—another fascinating convergence.

A third story that Williams is exploring is that of Samson Occom, a member of the Mohegan nation in Connecticut who became a Protestant minister. Occom studied at the “Latin School” of Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock in 1743 and went on to become an important missionary to fellow Native Americans in New England.

Occom was mentored by Wheelock, who originally founded the school for Indians, but then later moved the school from Connecticut to New Hampshire, where it became what is now Dartmouth College. The school was opened up to white students, which Occom saw as a betrayal of its mission to Native Americans.

In a letter of protest to Wheelock, Occom uses a Latin pun, referring to the school as an “alba mater,” rather than “alma mater”—with “alba” being a Latin word for “white.”

“My project is less about how things have been brought to Native American people, and more about how Native Americans have used things from European culture,” Williams says. “I want to see how Indian people learned Latin and Greek, the prestige languages of European culture, and what they did with them. This is part of a larger story about adopting, adapting, and surviving.”