Baseball was still a relatively young sport when roughly 20,000 people packed the small Oklahoma City stadium that was designed to hold less than 10,000. With the stands filled, a multitude lined the outfield foul lines, leading one reporter to wisecrack that “any guy ought to be able to pitch with 7,000 outfielders.”

What made the scene even more remarkable was that thousands of fans had come out to see an interracial baseball game, even though the year was 1934—over 10 years before Jackie Robinson broke the infamous “color line” by becoming major league baseball’s first African American player in the twentieth century.

What’s more, the fans were both black and white, wreaking “havoc with Jim Crow customs,” writes Timothy M. Gay in his book, Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert. “It was virtually unheard-of in the Oklahoma of that era for massive numbers of blacks and whites to interact on common ground. But thousands did that night, scrambling for balls that were hit into the outfield’s standing-room sections.”

LAS history professor Adrian Burgos used Timothy Gay’s book in his first “Sport and Society” course taught back in 2012. This fall he is offering the class once again, but this time the U of I course will touch on integration in boxing and collegiate sports in addition to baseball. Burgos sees his course as a way to examine integration in the broader society by looking through the lens of athletics.

In the Oklahoma City game of 1934, the crowds had come out to see St. Louis Cardinal superstars Dizzy Dean and his brother Daffy Dean. The two white pitchers had teamed up with local semi-pros to play a Negro League team, the Kansas City Monarchs. This was the barnstorming era of baseball, in which major leaguers and minor leaguers, as well as white players and Negro League players, crisscrossed the country in the off-season, playing exhibition games, says Burgos.

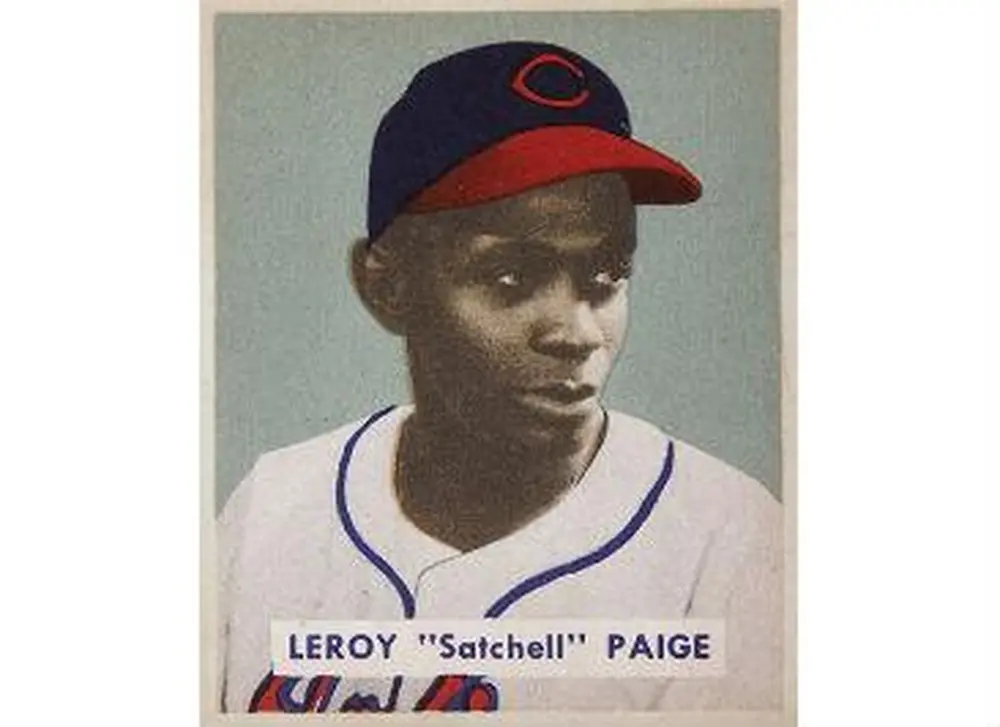

Although major league baseball remained segregated until 1947, the barnstorming tours of Dizzy and Daffy Dean featured an African American headliner—the legendary pitcher, Satchel Paige, perhaps the best Negro League pitcher of all time.

Black players such as Paige were obviously aware of the risks of barnstorming against white teams, so before they would venture south their contracts had to guarantee their safety. Paige drove his own car to barnstorming games so “he could escape potential dangers,” Burgos points out. “Paige didn’t have to wait on the bus. He could hop in the car and get going.”

Because Paige was so popular and because barnstorming brought the games to many cities without major league teams, Burgos says some people speculate that more fans may have seen him play live than Babe Ruth. As a headliner, Paige was the main attraction for both white and black fans, as were the Dean brothers and, later on, Hall of Fame-bound Bob Feller (nicknamed “Rapid Robert”).

“Barnstorming demonstrated that fans would come out to see an integrated game,” Burgos says. “The fans enjoyed it because unlike what was happening in the major leagues, you got to see the top players from across the racial spectrum right in front of you.”

In the first decade of the 1900s, well before the Deans, Paige, and Feller, many barnstorming teams were intact professional teams. For instance, the Cincinnati Reds would play Cuban teams during winter tours of the island.

“But the Cuban teams, which had some black Cuban players and African American players, played competitively and in some cases were equal to the major league teams,” Burgos says. “This weakened the case for segregation because part of the case was that these guys weren’t good enough.”

Embarrassed by the lack of dominance by white major league teams, American League Commissioner Ban Johnson declared that intact pro teams could no longer play black teams. From that point on, the white teams were all-star teams of sorts, consisting of a mixture of major and minor leaguers, such as the teams headlined by the Deans and Bob Feller.

As this fall’s Sport and Society course expands to include collegiate sports, Burgos says one of the new books he is using is the University of Illinois Press book, Benching Jim Crow, by Charles H. Martin. Benching Jim Crow includes the story of University of Alabama football coach Bear Bryant’s decision to recruit African American players so his team could remain competitive with schools that had integrated teams.

In the early to mid 20th century, Burgos says, there had been a “gentleman’s agreement” that northern schools would leave African American football players home whenever they played southern universities. But when northern schools began to ignore this unwritten agreement, segregation on southern teams, such as Alabama, began to fall apart as they scrambled to remain competitive.

“I designed this class so students could examine sports ultimately as both a mirror of society as well as a laboratory,” Burgos says. He points out that during the 1940s through the ’60s, when many sports began integrating, “Questions about integration and mutual opportunity were more easily explored on the field of competition than in the office. What I want students to draw from this class is that baseball can help us study hard questions.”

Society was willing to grapple with integration in sports, even before lunch counters were integrated, because people told themselves that “it’s just baseball,” Burgos says. “But Jackie Robinson and others who followed made sure it wouldn’t just be baseball.”

In the words of Satchel Paige, the integrated barnstorming games “put a little dent in Jim Crow.”