Mosquito bites are an itchy and annoying drawback to the fact that warmer days are upon us. But for many this year, mosquitoes could prove to be more than a mild nuisance, but rather a serious health hazard.

In mid-January, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a travel alert for Mexico, Central America, South America and the Caribbean because of the outbreak of Zika virus in the areas. Zika is spread through the bites of mosquitoes, specifically the species referred to as Aedes aegypti, otherwise known as the yellow fever mosquito for its place in the ecosystem as the primary vector for the virus that causes that disease.

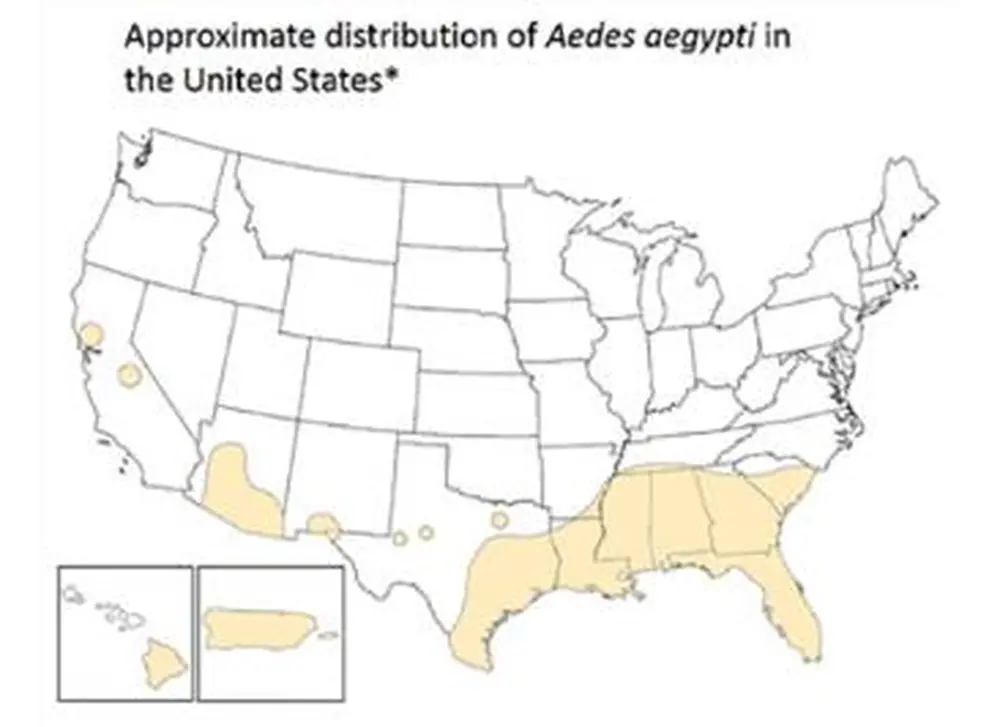

Aedes aegypti likes tropical and sub-tropical climates, with its northernmost range in the southern United States, according to the CDC. In February, the first U.S. case of Zika virus was reported in Houston. Since then, the disease has spread at an alarming rate—as of March 9, the CDC confirmed 193 reported cases of Zika in the United States. All cases have been travel-associated, though, meaning no one in the country has acquired the disease within U.S. borders by mosquito bite (there has been sexual transmission of Zika within the U.S.).

However, Puerto Rico has been afflicted with 159 locally acquired cases reported, so the travel-related distribution of Zika remains a pressing issue.

Brian Allan, an assistant professor in the Department of Entomology, has been following Zika since its outbreak and is currently working on research proposals to further explore causes and preventions of the virus. He is an expert in disease ecology and medical entomology.

“It’s definitely concerning,” Allan said. “The virus itself is generally a mild illness for most people, but there’s a lot of evidence that it can cause a very serious disease in a developing fetus.”

The symptoms that come with Zika are generally mild and flu-like, including fever, rash, joint pain and bloodshot eyes. Just one in five people infected with Zika experience symptoms, according to the CDC.

However, the real health concern arises when pregnant woman are exposed to Zika. The disease has been strongly connected to microcephaly, a birth defect that leads to smaller-than-normal head sizes for infants. This condition leads to abnormal brain development and is often life threatening.

In Brazil alone, 4,000 cases of microcephaly—20 times the country’s usual amount—have occurred since the first case of Zika in Brazil was reported in May 2015.

“For pregnant mothers and their developing children, it’s a very serious pathogen,” Allan said.

Because of the tropical and sub-tropical regions that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes thrive in, most U.S. cases of Zika have occurred in southern states—68 of the 193 cases were reported from Texas or Florida. However, 31 different states have had at least one case of Zika.

Since vaccine development could take years, prevention will be the key to limiting the transmission of Zika. According to Allan, simple measures such as turning over bird baths or draining storm-water drains could limit the sheer number of mosquitoes since they tend to breed in predominately aquatic environments.

Seven cases of Zika have been confirmed in Illinois, but Allan doesn’t believe Midwesterners should be any more afraid of mosquitoes as they usually are.

“People should take the threat very seriously but they should be informed as to what the threat is,” Allan said. “There’s a very low chance of extended transmission of Zika virus here in Illinois. We’re too far north for the current range of Aedes aegypti.”

While Zika is still confined to a relatively small part of the country, it may be a good idea to take some simple precautions against mosquito bites if you’re in range of Aedes aegypti. The CDC suggests wearing long sleeves or pants, using nets or screens to keep mosquitoes away as you sleep and using insect repellent as directed.