Biochemists at the University of Illinois have isolated a protein supercomplex from a bacterial membrane that, like a battery, generates a voltage across the bacterial membrane. The voltage is used to make ATP, a key energy currency of life.

The new findings, reported in the journal Nature, will inform future efforts to obtain the atomic structures of large membrane protein supercomplexes.

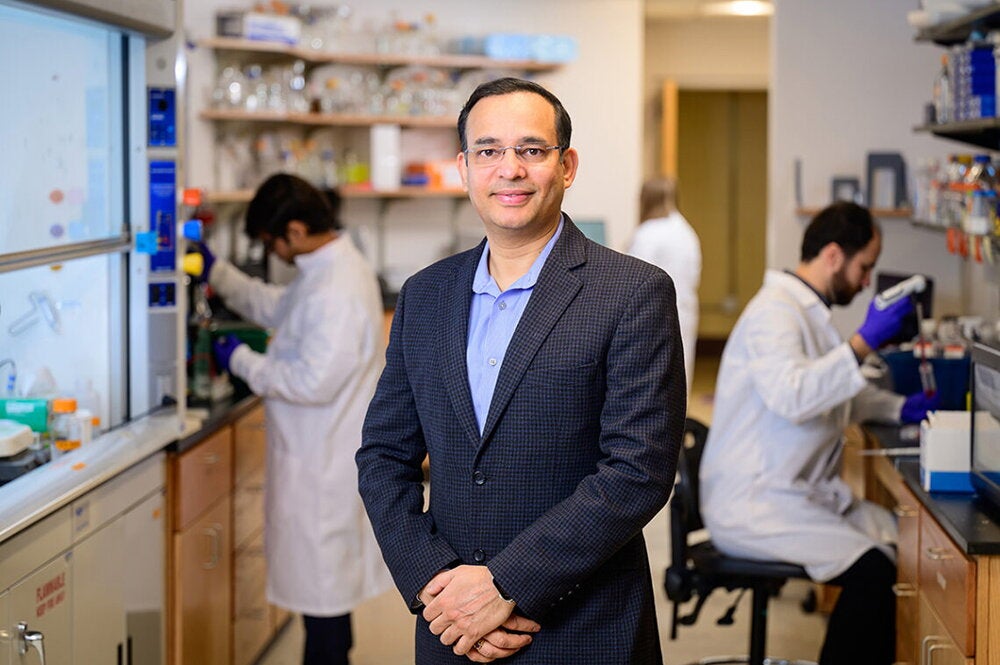

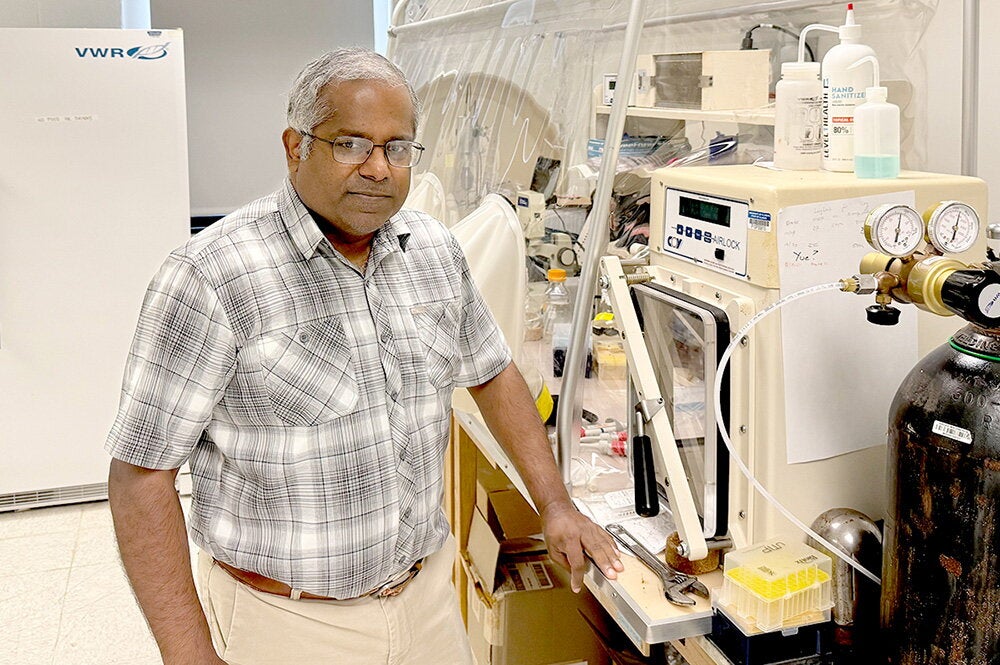

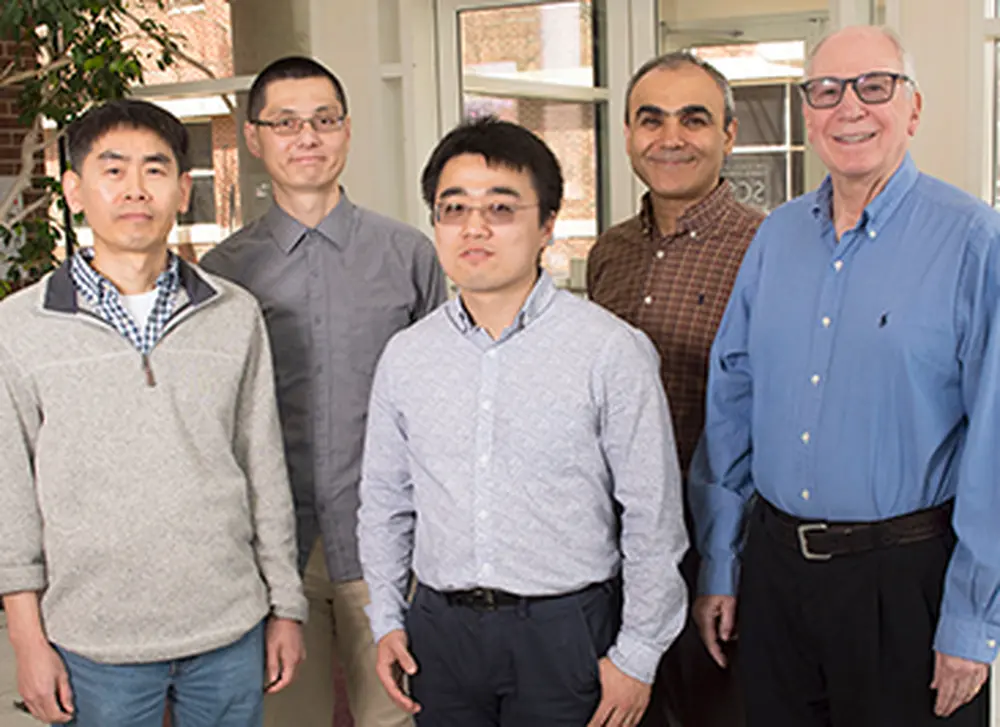

“With billions of years of evolutionary experience, bacteria are adept at surviving in changing environments,” said Robert Gennis, a University of Illinois professor emeritus of biochemistry in the School of Molecular and Cellular Biology who led the new research with Emad Tajkhorshid, J. Woodland Hastings Endowed Chair in Biochemistry. “Most have the ability to modify, replace or combine molecular tools to suit the new demands – sometimes within a single cell’s lifetime,” Gennis said. These tools include enzymes, which catalyze chemical reactions to perform specific tasks.

The research was initiated by Illinois alumna Padmaja Venkatakrishnan (PhD, '16, biochemistry), now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis.

The energy required by the bacterium is obtained by transporting electrons from high energy food molecules to oxygen, similar to what occurs in plant or animal cells, Gennis said. Electrons pass from one enzyme to another until finally reaching oxygen.

Typically, an enzyme passes an electron on during a random collision with another enzyme. The researchers showed that in some conditions, nature eliminates the need for random collisions by sticking the enzymes together to form a “supercomplex.” Each part of the supercomplex can generate a voltage, but all parts must function in sequence, Gennis said.

“It makes sense that they will function as a single unit to make sure the electron transport is rapid and the electrons end up where they belong,” he said. “Supercomplexes are probably important in all electron transport chains, but in most cases, attempts to isolate them fail because they fall apart. We were lucky to be studying an organism called a Flavobacterium, in which the supercomplex is stable.”

Rather than relying on detergents to extract the proteins from the membrane, as is typically done in such experiments, the team tried an industrial polymer – a kind that plastics are made from. Using this polymer, they extracted and isolated the supercomplex in a single, rapid step. The process embedded the supercomplex in a small disc of membrane shaped like a coin.

With the help of their collaborators at the University of Toronto and the New York Structural Biology Center, the team used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the configuration of the supercomplex components.

“Evolution has resulted in a very efficient ‘nano-machine’ that is also beautiful to look at. Seeing how this works gives one a great appreciation of nature and is one of the joys of doing science,” Gennis said.

The National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported this research.