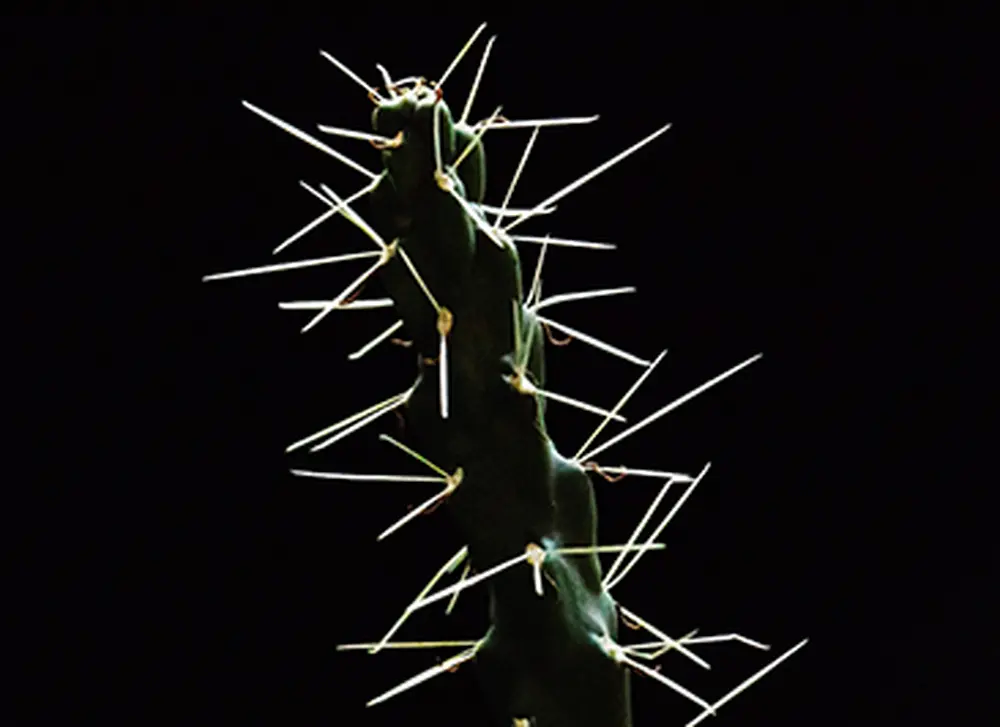

Beware the jumping cholla, Cylindropuntia fulgida. This shrubby, branching cactus will – if provoked by touching – anchor its splayed spines in the flesh of the offender. The barbed spines grip so tightly that a segment of cactus often breaks off with them, leaving the victim with a prickly problem.

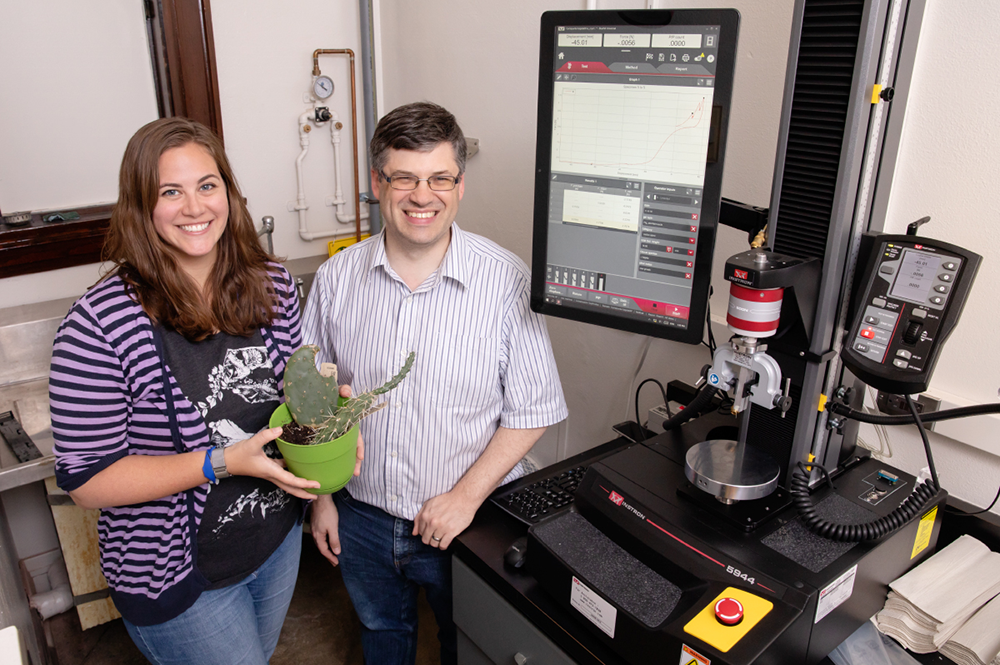

This is one of six species of cactus subjected to careful testing by University of Illinois postdoctoral researcher Stephanie Crofts and animal biology professor Philip Anderson. The researchers, who study the biomechanics of puncturing plants and animals, wanted to know how spine structure influences its performance.

They found that the same biomechanical traits that allow barbed cactus spines to readily penetrate animal flesh also make them more difficult to dislodge. The researchers report their findings in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"We're looking at the fundamental mechanics of a puncture event and how differences in cactus spines – in particular their microstructure – affect how they puncture and anchor into whatever they're puncturing," Crofts said.

In addition to cholla, the researchers evaluated the spines of Echinocactus grusonii, the golden barrel cactus; Opuntia fragilis, or brittle prickly pear; Pereskia grandifolia, the rose cactus; Echinopsis terscheckii, the Argentine saguaro; and Opuntia polyacantha, the plains prickly pear.

Cactus spines may have a variety of functions, including defending the plant from predators, providing shade and collecting water from fog. Cholla spines have a reproductive purpose: By latching on to any critter unlucky enough to brush past them, the spines help the plant distribute pieces of itself to new locations.

To compare the different spines, Crofts and Anderson tested them in skinless chicken breasts, pork shoulders (with the skin) and synthetic elastomers of differing densities. They measured how much force was required to puncture - and withdraw from - each material with each type of spine.

"Before we started the experiments, we looked at the spines under a scanning electron microscope," Crofts said. "The barbed spines – like those on the cholla – looked incredibly similar to porcupine quills studied by other groups."

Like porcupine quills, barbed cactus spines have a shingled appearance, the result of overlapping layers of barbs. And, like those on the porcupine quills, the cactus barbs are just the right size to snag animal muscle fibers, the researchers discovered.

Spines without barbs required more work to initiate fracture, the researchers found. Barbed spines more readily penetrated their targets and required less work to do so. They also were more difficult to remove from animal tissue.

"In order to puncture effectively, the cholla spine has to be able to penetrate the target very easily, so that just a slight brushing is all it takes," Anderson said. "At the same time, it has to be really hard to remove."

In porcupine quills and barbed cactus spines, the barbs act like little sharpened blades that concentrate the stress and cause the animal tissue to fracture more easily, Anderson said.

"Then the barbs catch on your muscle fibers, making it difficult to remove them," he said.