It's hard to talk about fish in Illinois without talking about Lawrence M. Page.

In fact, it’s difficult to talk about the fishes of North America and Southeast Asia without mentioning Larry Page.

That’s because Page has spent much of his career researching, identifying, collecting data about and specimens of, teaching about, curating collections of, and publishing on freshwater fishes, particularly their evolution and evolutionary relationships. It’s those contributions as a scientist, teacher, and mentor that led to Page’s recognition as one of the 2023 LAS Achievement Award winners.

“[He] has dedicated his life to describing and protecting biodiversity,” wrote Becky Fuller, who studied ichthyology with Page and now is head of the Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Behavior. “Larry’s philosophy is that there is compelling, underappreciated diversity all around us, and that this diversity is worth preserving.”

Page grew up in Lexington, Illinois, where family camping trips and a household aquarium first sparked his interest in the natural world, particularly fish. When he came to the University of Illinois as a graduate student, “working with fishes in the lab sort of cemented my future,” he said.

Page earned his master’s (1968) and PhD (1972) in zoology (now evolution, ecology, and behavior), then joined the staff of the Illinois Natural History Survey. INHS is committed to researching, monitoring, and preserving the ecology and biodiversity of Illinois, a mission that matches Page’s own passion.

“Going to the INHS had a huge impact on what I wanted to do after I got my PhD, which was continue studying the evolution and ecology of freshwater fish,” Page said.

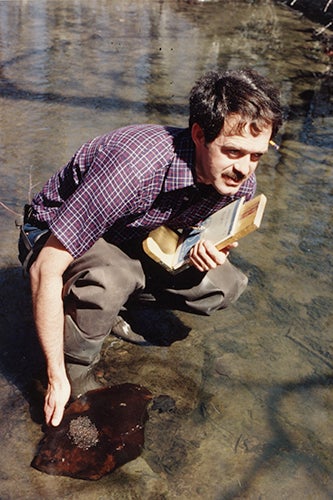

While at INHS, Page participated in the development of an incredible long-term record of Illinois’ fishes. The data collection began in the late 1800s, when noted naturalist Stephen A. Forbes and Robert E. Richardson traveled the state via horse and carriage, documenting what fish species were present and where they were located. The specimens they collected from Illinois’ rivers, streams, and lakes remain part of the INHS research collections today. Phil Smith (Page’s PhD advisor) repeated this statewide survey in the 1950s to early 1970s, and then Page and his colleagues conducted a third survey in the 1980s to early 2000s. By surveying the state repeatedly over 150 years, scientists developed a singular record of fish distribution and abundance.

“These surveys are a way of documenting changes in the environment, and they allow us to look at long-term changes, such as impacts from evolving land use and climate change,” said Page. “It’s overwhelmingly important.”

Page and several co-authors recently shared this comprehensive data on Illinois’ 217 current and extirpated fish species in An Atlas of Illinois Fishes: 150 Years of Change. This is the latest of nine books Page has authored, along with more than 200 scientific articles.

A recurring theme in Page’s career is that there’s always something more. After researching and teaching at U of I for 32 years, he “retired.” Which meant that he left Illinois to serve as a program director at the National Science Foundation for two years and then moved to the Florida Museum of Natural History, where he is currently curator of fishes. When asked what he’s most proud of in his career, Page paused, seemingly reluctant to boast. There are the books, and the dozens of graduate students he’s trained, who have gone on to do research and work with biological collections across the country. And there’s his seven-year stint helming iDigBio, a massive effort to digitize the data and images from millions of biological specimens to make them more widely available to scientists, conservationists, educators and students, and the public. And then there’s whatever he’ll do next.

His research now has turned primarily to Southeast Asian fishes. He’s been returning to the region at least once a year since 2005, including a 2021 Fulbright-supported study of the freshwater fishes of Thailand.

“So much less is known than we know about fishes in North America,” he said. “And we can’t study ecology and behavior until we know what we’re working with, the distribution of species. I find that very exciting.

“And it’s great fun! I’m still enjoying it very much.”