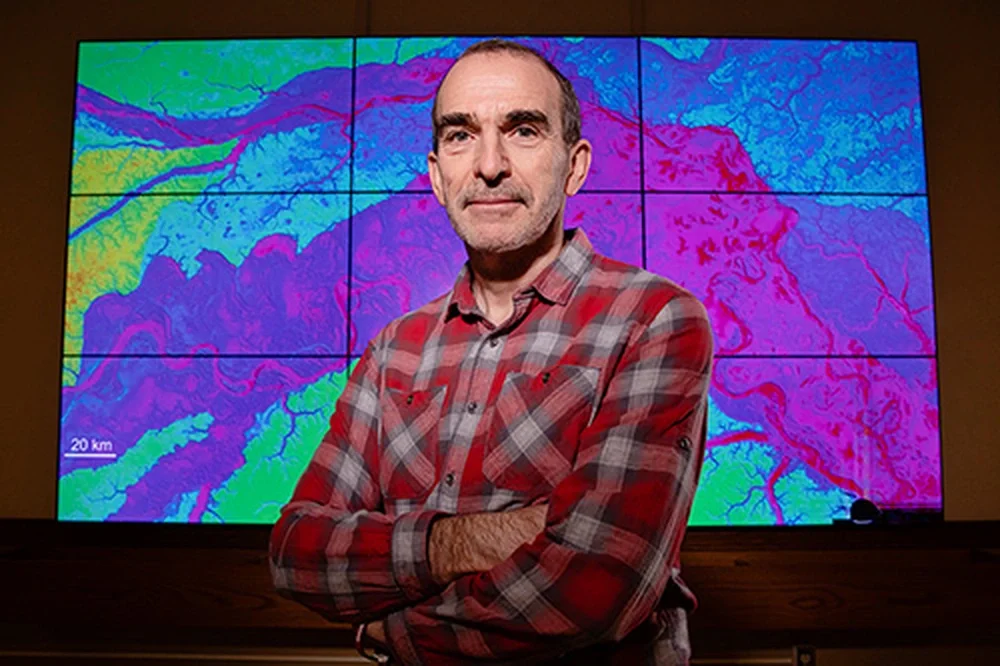

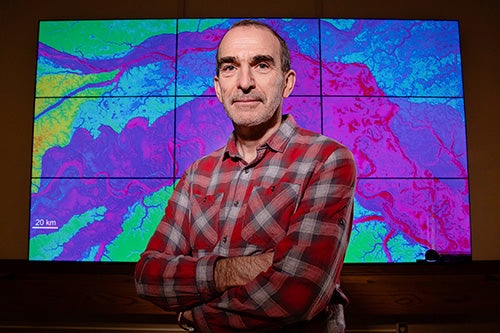

After making landfall, Hurricane Helene moved north and dumped an enormous amount of rainfall onto the mountainous regions of Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee, leading to catastrophic flooding hundreds of miles away from the storm's initial landfall location. Professor Jim Best, an earth science and environmental change expert, discussed the event and future ones like it with Illinois News Bureau editor Lois Yoksoulian.

The regions affected by this event are far away from Helene's landfall and are typically not associated with risk from tropical storm flooding — especially storms originating from the Gulf of Mexico. Are there other far-inland areas at risk from severe flooding from tropical storms?

Yes, depending on the track of the storms, inland areas can be affected. I remember events in the last 15 years that have brought increased rainfall across the Midwest region, and such impacts will occur in the future. The areas impacted depend on the hurricane's path, size, moisture content and speed at which it progresses — all of which affect the amount of water delivered in rainfall.

There are maps that show the postlandfall tracks of Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico hurricanes that have affected the weather in the Midwest in recent years. On the West Coast, we’ve seen the massive impacts of what are called "atmospheric rivers" over the last few years. These bands of high moisture content are sometimes associated with tropical cyclones, and postlandfall paths are essential to forecasting the potential location and magnitude of flooding.

One word we keep hearing associated with this natural disaster and many others like it over the past few years is “unprecedented.” How true is this, and do you think events like this might become more of the norm in the future?

If we look at this flooding event and others worldwide over the last decade, there is clear evidence that floods in many regions are becoming larger in size and more frequent. The impacts are not uniform spatially and will also show different patterns in different areas as we look into the future. Changing climate, weather, and flood and drought patterns are inevitable. However, these changes combined with increasing human populations mean that the impacts of these extreme events will be felt increasingly across the globe.

Of course, we need to consider and address these impacts not only here in the U.S. but also in other countries. As we have seen in the last few years, climate-related natural disasters greatly impact human migration, economic development and political thought.

The hazards presented by water during active flooding are somewhat obvious, but what kind of hazards lurk in the aftermath of a flooding event like this?

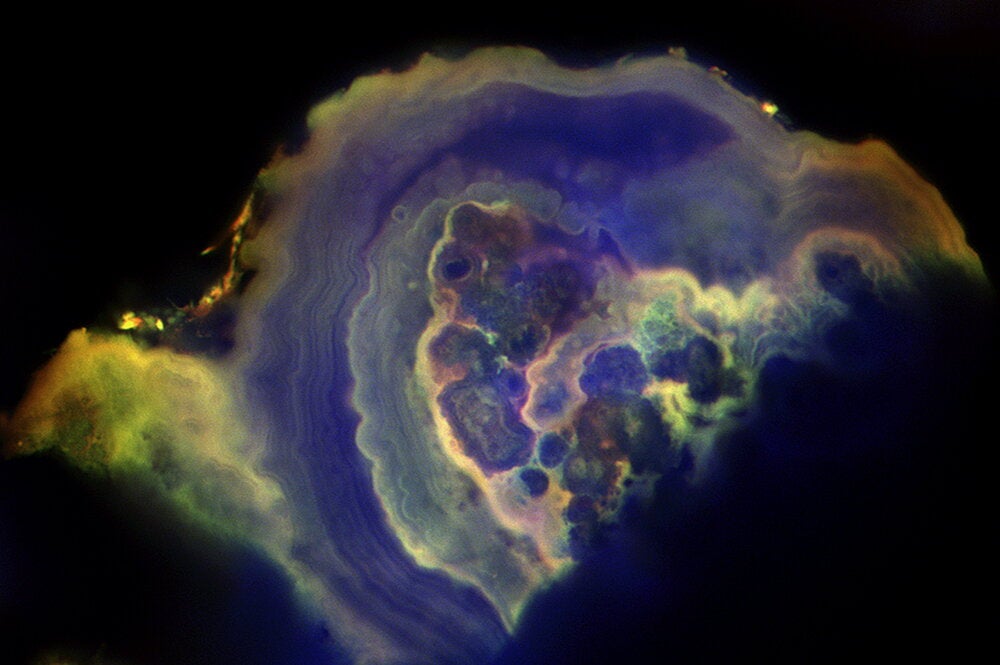

Flooding is about much more than just water. Beyond the initial chaos that comes with the water is erosion of the land and the transport and deposition of a lot of sediment that changes the landscape and the human infrastructure built there. So, we must deal with these changes — from washed-out roads to eroded riverbanks, damaged bridges, houses and altered streams and rivers. Understanding how sediment moves during flooding events and assessing how it affects infrastructure are critical in helping minimize any longer-term damage. When sediment-laden floodwaters recede, the layout of the water supply network will be significantly altered, and the changes and damage wrought by the newly dumped sediment can alter the landscape for a long time.

If we look at other countries that have been severely impacted by floods — such as Pakistan, India and Bangladesh — substantial areas of rich cropland have been destroyed, which has led to food shortages over a period of months to years. The long-term impacts are enormous — from food shortages to human migration to social inequalities to crime and violence. Such impacts then demand a longer-lived response to these flood events in aid, infrastructure repair, and human health.

Finally, floods can also erode sediments containing pollutants such as heavy metals, microplastics, nitrates and phosphates, freeing them to remobilize in the environment.

What can be done to help mitigate future flooding events like this?

We need to view these events and the timescale of their causes and effects over different scales.

On a longer time scale, there is the burning issue of how we better deal with a changing climate and reduce the impact of greenhouse gases. This is a global issue, but the U.S. can play a leading role in promoting education, political will and acceptance of the evidence that is staring us in the face. We must continue to develop solutions and policies we can enact now as we see the evidence of the impacts of a changing climate across the globe.

Long-term support for government entities such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency will be vital. These organizations fuel exciting new technologies that help monitor, model, and predict extreme weather, such as remote monitoring of waters from space. Continued support for this science is needed because monitoring is vital to hazard assessment, prediction and alleviation.

Strategies to help cope with such floods can also help, and we need a range of measures that will differ in different regions. For example, it makes no sense for us to build new infrastructure in flood-prone areas, so restricting construction in floodplains will reduce the risk of extreme inundation. When we do build on floodplains, we can create a more resilient infrastructure that can better adapt and cope with flooding. There are techniques we can use to help existing river channels be better managed, such as setting aside floodplain areas to cope with storing floodwaters.

On a shorter time scale, we need to constantly improve and develop better strategies for coping with the impacts of such events — both in our preparedness and in helping communities deal with and recover from such events. The role of local and federal government is vital here, together with residents and regional and local organizations. If flooding is predicted, how well we support communities before, during and after these events to help minimize impacts on human health, infrastructure and economy will be critical. Again, we need to view flooding as far more than just water and enable coping strategies for impacts on both the physical and human landscapes that future floods will impact.