The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with federal and state health agencies to address a widespread outbreak of bird flu among dairy cows, poultry, and other animals in the United States. More than 150 million farm birds have been slaughtered to prevent the disease’s spread, which has been a factor in a dramatic rise in egg prices. Is the end in sight? What are the risks? We asked Chris Brooke, professor of microbiology at U of I.

What is bird flu, and how does it spread?

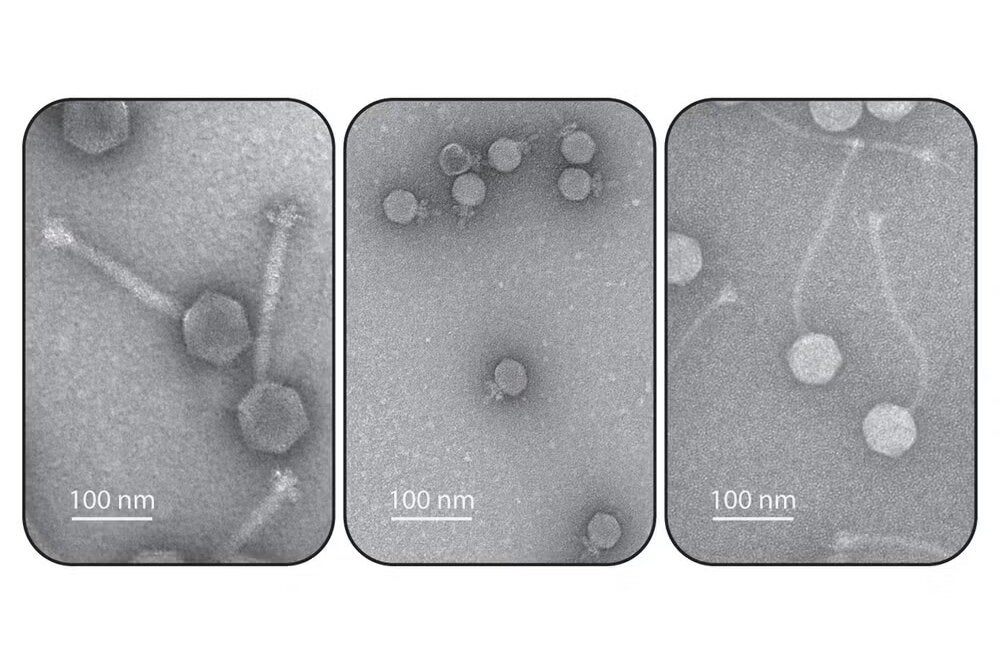

“Bird flu,” also known as “avian influenza,” includes a large, diverse array of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds and spread via either the respiratory or gastrointestinal route. Most strains of bird flu are generally mild in birds and have little to no risk of infecting people. The strains of bird flu that people tend to worry about are the strains that are referred to as “highly pathogenic,” since they can cause mass die-offs in bird populations, including chickens, and can cause very severe disease and death in humans.

What makes the current strain of bird flu different than previous strains?

The strain of bird flu that has people concerned right now is a specific lineage of the highly pathogenic avian H5N1 subtype called “2.3.4.4b.” This viral lineage began sweeping through bird populations across the globe several years ago and, most concerningly, has subsequently crossed over and established itself within multiple different mammal host populations. In the past, infections of mammals with H5N1 or other bird flu strains were generally dead ends because the virus was incapable of transmitting from mammal to mammal. This 2.3.4.4b lineage is of great concern because it has already shown that it can readily establish outbreaks and sustained transmission within multiple mammalian species, including marine mammals, dairy cattle, and minks. Once a strain of bird flu can reliably transmit between mammals, the risk becomes much greater that it will gain the ability to transmit between people and potentially cause an epidemic or pandemic.

Do you see this becoming a worsening issue?

Yes, unfortunately. This new lineage of H5N1 is clearly capable of mammal-to-mammal transmission in multiple species – something we have never seen any strain of bird flu do before. The more mammalian hosts the virus can infect, the more chances the virus has to evolve into something capable of sustained human-to-human transmission. So, I would say that the risks of an H5N1 pandemic have never been higher than they are today. This is also happening at a time when the current administration is hobbling the public health infrastructure (e.g. Centers for Disease Control, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Agriculture) that we usually rely upon to work to control the spread of dangerous pathogens like H5N1.

Signs on campus are advising people to stay away from geese. How great is the risk of transmission from geese to humans?

I think because geese are natural hosts of influenza virus and may be infected with 2.3.4.4b viruses, it makes sense to avoid them as much as possible. For now, the risk of contracting bird flu is virtually non-existent if you are not in close contact with infected animals or handling unpasteurized products of infected animals (i.e. raw milk). (And) I would just recommend avoiding close contact with wild birds if possible.