If you looked out your window and saw a tree, and then blinked and the tree was gone, you'd notice it was missing right? Researchers studying change blindness, the term characterizing when someone fails to be aware of significant changes in scenery, say that there's a good chance you wouldn't notice a thing. According to these researchers, we are aware of only a small portion of what our visual system makes available to our brain, and unless we pay attention to an object, both before and after it changes, we will not notice the change.

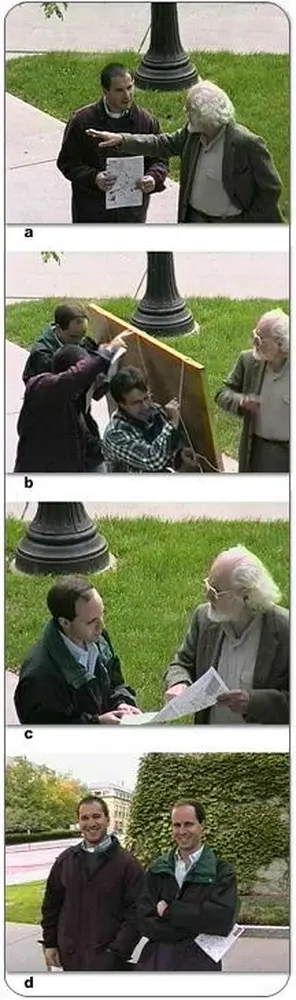

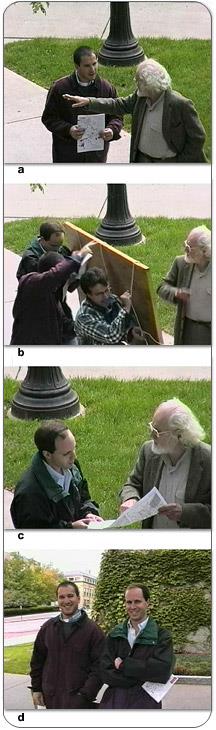

Associate psychology professor Daniel Simons runs the Visual Cognition Laboratory at the Beckman Institute and uses various experiments, often involving real-world settings, to investigate change blindness. In one experiment, Simons had a researcher approach a pedestrian and ask for directions. While the two were talking, two other people, carrying a door, rudely cut between them. At the point when the pedestrian's view of the experimenter was obstructed, the experimenter was replaced by another person. Only 50 percent of the people in the study noticed the difference, even though the two experimenters wore different clothes, were different heights and builds, and had noticeably different voices.

Change blindness, such as in the door example, is one reason why eyewitness testimony is not always reliable. A related phenomenon called inattentional blindness is a possible explanation for why drivers get in accidents. Simons says that people may look but not see a danger in front of them. In one experiment, subjects viewed a video of two teams of players passing basketballs to each other. One team wore white shirts and another wore black shirts, and subjects were instructed to count the number of passes between members of the white team and to ignore the activity of the black team. After about 30 seconds, a person dressed in a gorilla costume walked into the middle of the game, turned to face the camera, thumped its chest, and walked off the other side of the display.

Despite how out-of-place the gorilla was in the context of the game, less than 50 percent of observers saw it at all, and most were astonished that they could have missed it when shown the video a second time. The results, says Simons, speak to the importance of attention in visual perception. "We found that the more focused people were on their counting task, the less likely they were to notice the gorilla."