Chemists in LAS have produced a molecule that selectively kills cancerous cells in a desired way and leaves healthy cells virtually untouched.

While encouraging, the findings don't mean a new treatment is imminent. The basic laboratory experiments were done in microtiter dishes, where the compound was simply exposed to leukemia and lymphoma cells and healthy white blood cells from mice.

"It's hard to say where this discovery may fit into the big picture, but the pathway we've found is real; it is very provocative," says Paul J. Hergenrother, a professor of chemistry, who directed the study funded by the National Science Foundation.

The study appears in the December 3 issue of the Journal of the American Chemical Society. The compound, which is referred to as 13-D in the study, already is being tested by the National Cancer Institute. The University of Illinois has applied for a patent on it.

"The next big step would be to show that this compound works in an animal model," Hergenrother says. "We are very interested in the selectivity of this compound. We now are trying to track down exactly what protein target this compound is binding to in the cancer cells. If we can isolate the protein receptor, we may find a totally new anti-cancer target."

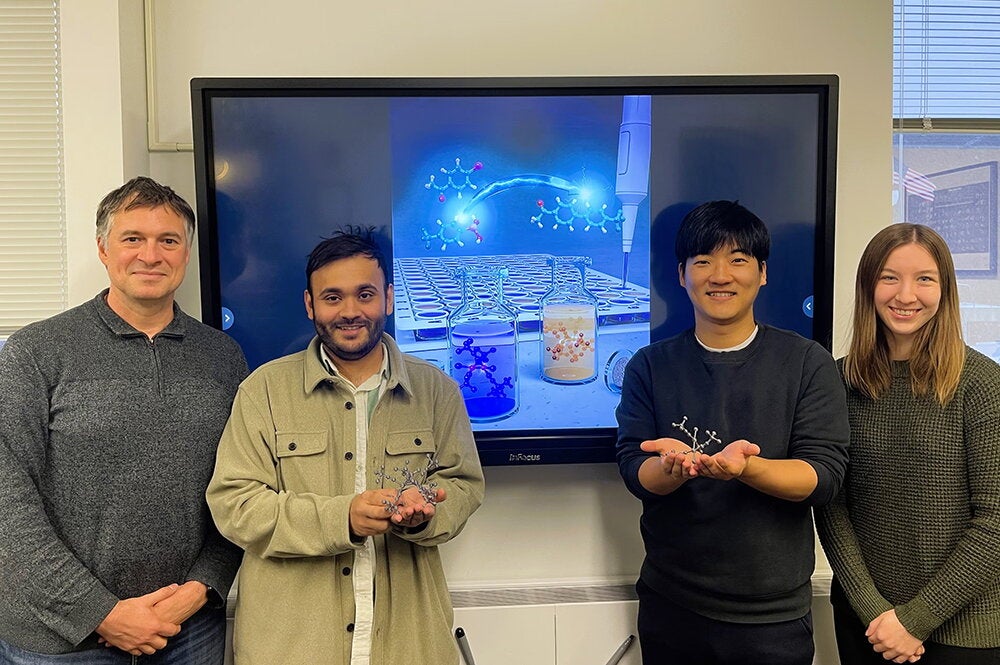

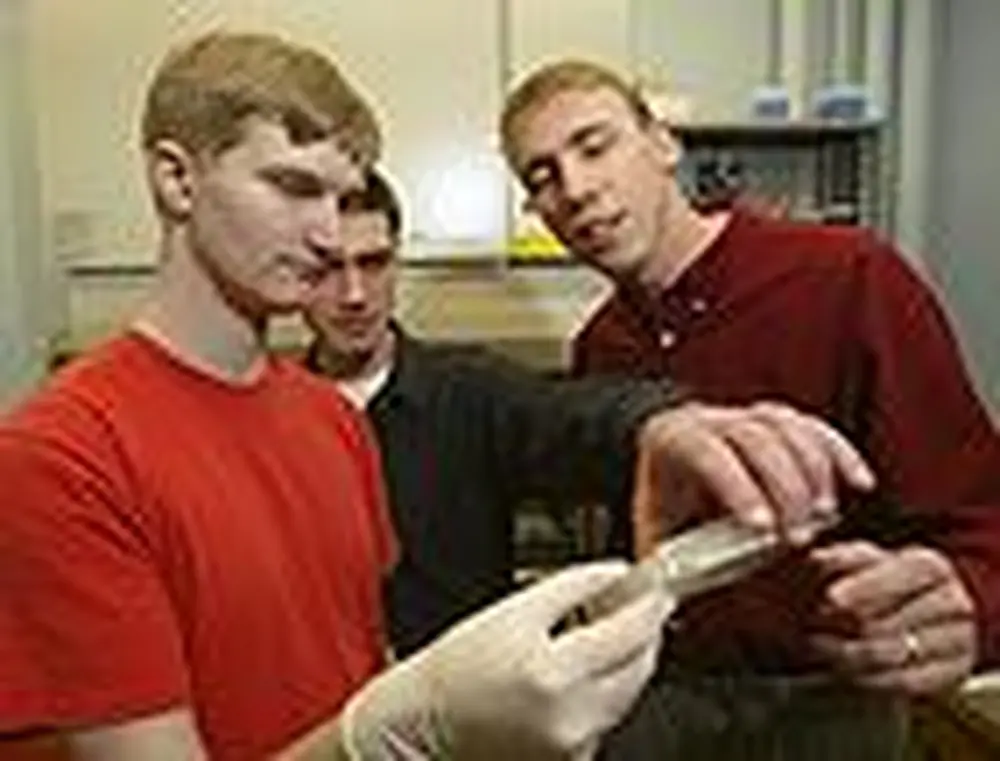

Hergenrother and his doctoral students Vitaliy Nesterenko and Karson S. Putt manufactured a library of 88 artificial compounds based on the structures of certain natural products. Three of the compounds showed a significant ability to kill cancer cells. Those three were further screened to determine if they were killing the cancer cells through apoptosis or necrosis.

Apoptosis is desired because cells die in a programmed fashion and are simply engulfed by other cells. Necrosis is essentially an accidental breakdown that results in the spilling of cellular material that triggers an undesirable anti-inflammatory response.

Compound 13-D was found to have the strongest cancer-killing effect and the only one to induce a cysteine protease known as caspase-3 as well as blebbing (a pinching off of the cellular membrane) and cell shrinkage, all of which are hallmarks of apoptosis.

"Once we had a compound that killed by apoptosis, we did the key experiment to see if the compound induced cell death selectively, choosing cancerous cells over non-cancerous white blood cells," Hergenrother says. "Compound 13-D showed virtually no toxicity toward the actively dividing T-cells while almost completely killing the lymphoma and leukemia cells."

Such results are desirable, because many current human therapeutic approaches result in undesired side effects such as anemia and major gastrointestinal problems.

Additionally, Hergenrother says, if the biological pathways can be isolated it may be possible to manufacture compounds that not only encourage apoptosis in cancer cells but also inhibit it in healthy cells, a potential benefit to sufferers of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases in which many cells die off unnecessarily.