A modest five-cent tax on a gallon of gasoline paid today could mitigate long-term climate change in the future. The idea is the work of two U of I scientists and an economist from Wesleyan University, with funds from the National Science Foundation.

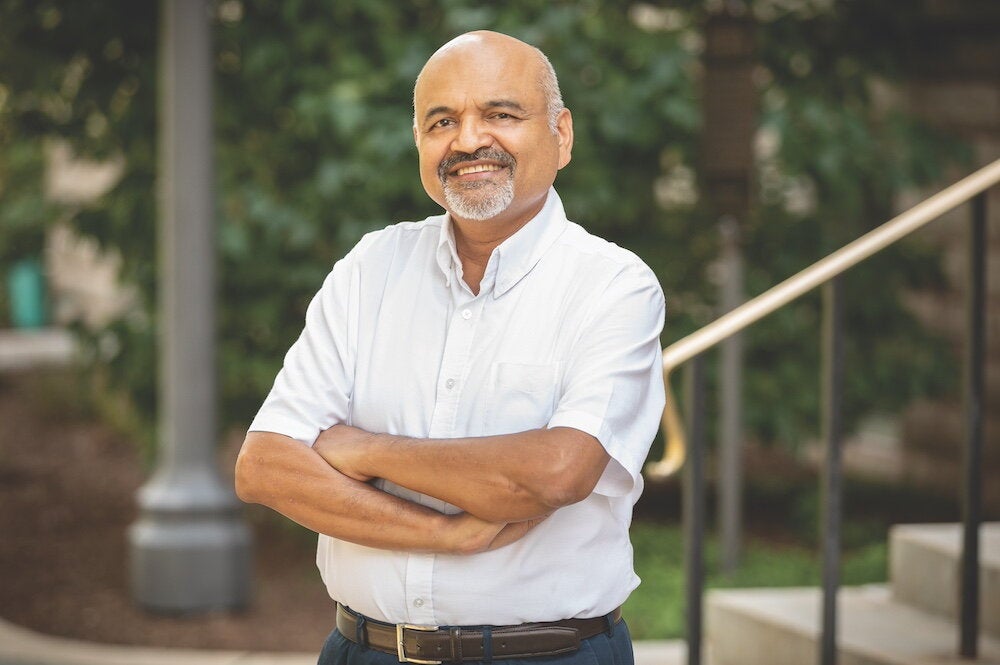

"You can think of the tax as a low-cost insurance policy that protects against climate change," says Michael Schlesinger, a U of I professor of atmospheric sciences. Those "premiums" could then be used to develop alternative technologies and help wean the United States from carbon-dependent energies.

Schlesinger fears that if the nation waits to see how the uncertainty of global climate change plays out it may not have the range of immediate options the tax brings. "By then, however, it may be too late and we will have foreclosed certain options. Rather, the uncertainty is the very reason we should implement climate policy in the near term."

Researchers found that the most inexpensive method is to implement a carbon tax that starts out at $10 per ton of carbon (about five cents per gallon of gasoline) and then gradually climbs to $33 per ton in 30 years. Such hedging effectively "buys insurance" against future adjustment costs and is extremely robust, especially when compared with a wait-and-see strategy.

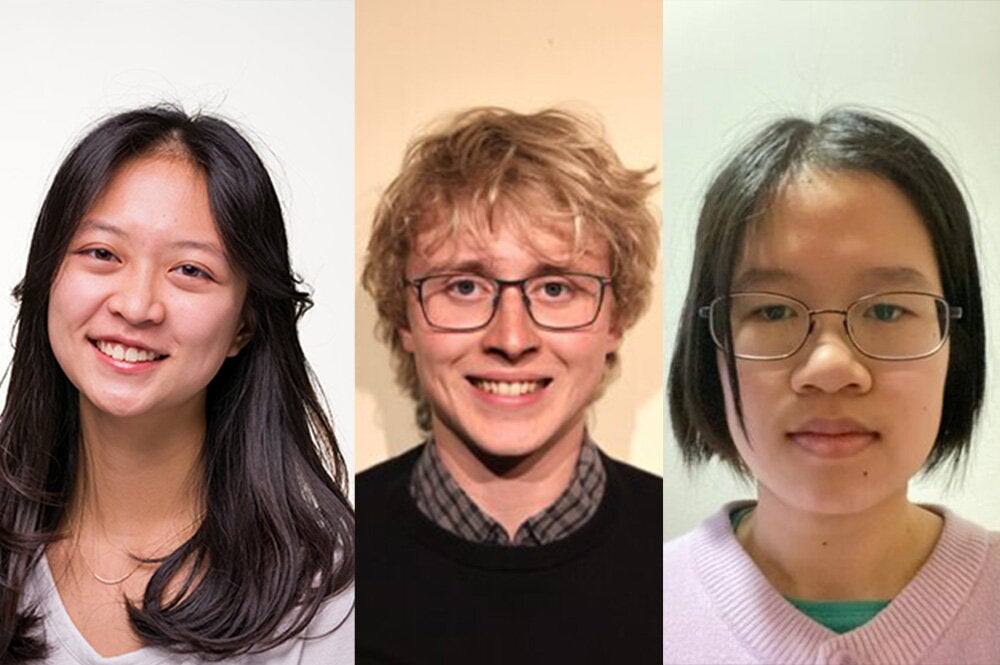

To explore the effectiveness of implementing near-term mitigation policies as a hedge against uncertainty, U of I atmospheric scientist Natalia Andronova, Wesleyan University economics professor Gary Yohe, and Schlesinger assumed that tax policies would go into effect in 2005 and continue for 30 years.

The team also incorporated a 2001 study by Andronova and Schlesinger of climate change ambiguity. In that report the two scientists used a simple atmosphere/ocean model to reproduce the observed temperature change from 1856 to 1997 for 16 combinations of the radiative forcing by greenhouse gases, the sun, and volcanoes.

"Recent work by five independent research teams has shown that climate sensitivity could be larger than the 4.5 degrees Celsius upper bound published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change," Schlesinger said. "In fact, climate sensitivities as high as 9 degrees Celsius are not implausible.

"The idea is to search for the tax that provides the least cost over the whole period. If the tax is too low, you do too little in the beginning, then after 30 years you have to do a lot. On the other hand, if the tax is too high, you spend too much now, and you may have to do only a little later."

Results of the research were published in the October 15 issue of Science.