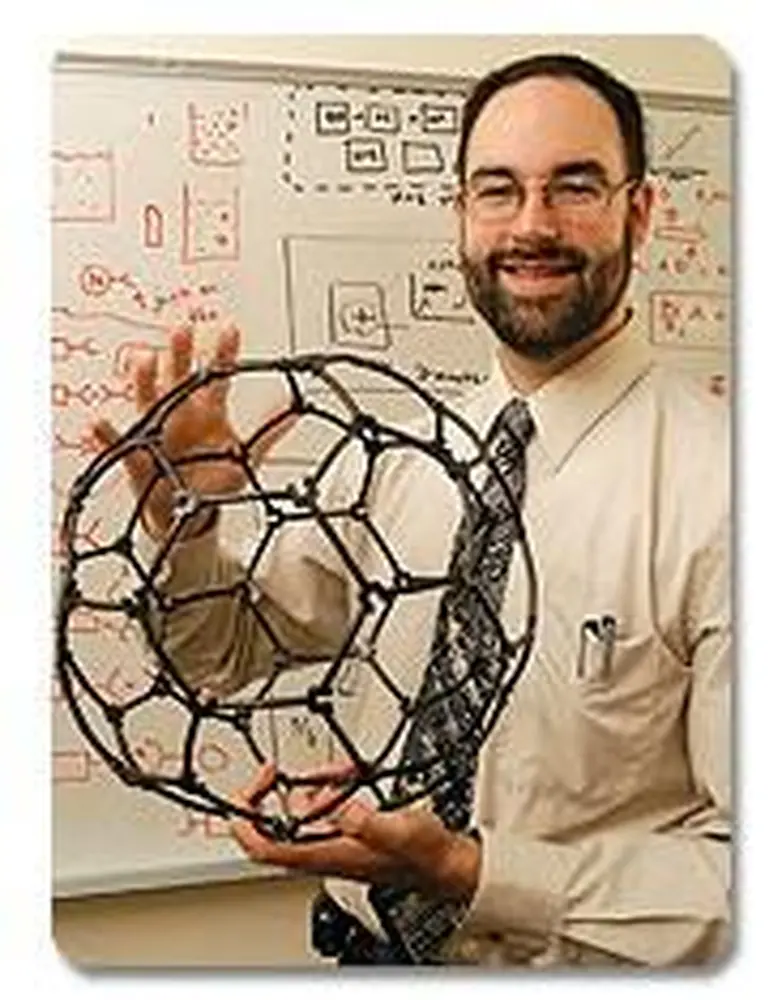

They're just the stuff to wire tomorrow's molecule-sized computer chips, make fibers tougher than Kevlar, even create cables for an elevator to space. Now LAS researchers have taken a giant step toward those ambitions by developing a method to separate different types of carbon nanotubes.

Just one ten-thousandth the width of a human hair and shaped like a minuscule roll of chicken wire, carbon nanotubes differ in their configuration and their chemistry. Some behave like metals, conducting electricity as well as copper wire, and some behave like semiconductors in computer chips, conducting electricity haltingly. To build computer chips, fibers, or other devices, researchers must first separate the two types of nanotubes. But that has proven difficult.

Michael Strano, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, solved the problem by adding a chemical called diazonium that bonds only to metallic nanotubes, forming a molecular handle that allows the chemists to pluck metallic nanotubes from the mix and purify them. Then they heat them to sear off the handles, yielding intact metallic nanotubes that are ready to use.

The procedure, which was published in Science earlier this year, provides "a new paradigm" by showing that the chemistry of carbon nanotubes depends on their electronic properties, not just their diameters, Strano says. Now, the researchers are using the method to make new materials that could take electricity made in Maine and deliver it to Oregon.