Paul Cziko drops through a hole, drilled through 20 feet of ice-a portal into the cold, dark world of the Antarctic Ocean. It takes only a little bit of snow on top of the ice above to cut off sunlight, plunging Cziko and his diving partner Kevin Hoefling into darkness.

The water is so cold that Cziko's lips, the only exposed parts of his body, quickly go numb. The water is frigid, but it is also amazingly clear-like the tropics, says Cziko, a 2004 LAS graduate with degrees in animal biology and biochemistry. When he shines his light, he cannot even see the water in which he's swimming. As he puts it, "I feel like I'm floating in space."

Although the Antarctic water may be as clear as the tropics, Cziko says it does not teem with the colorful fish you find in warm waters. Here, the species are few, and what fish they see are drab with big eyes and big mouths. In other words: they are downright ugly. That's why one particular fish caught Cziko's attention when he and Hoefling were diving in Antarctic waters in the "austral summer" of 2004-05 (which coincides with winter in the northern hemisphere).

"It was silvery and reflective, kind of a pretty fish," Cziko recalls. "It was a little more elegant." This fish was also larger than those they typically see in Antarctic water-although by "larger" he means only about a foot long.

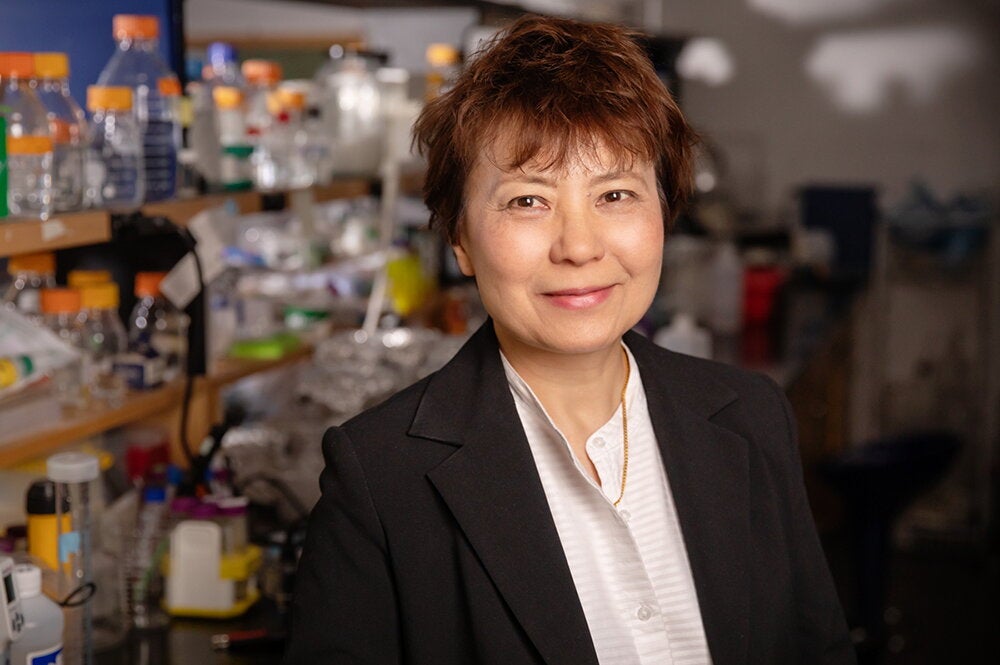

Little did he know that they had just stumbled across an entirely new species of fish. The discovery was recently announced in the journal Copeia, in an article co-authored by Cziko and LAS animal biology professor C.-H. Christina Cheng.

By making this "fortuitous find," as Cziko calls it, he was given the honor of naming the new species. He dubbed it Cryothenia amphitreta because "amphitreta" is the Greek word for "cave with two openings." The name refers to one of the distinguishing features of the new species-the shape of its interorbital pit, an indentation between the eyes of many fish. The new species' interorbital pit resembles a cave with two openings.

What brought Cziko into these cold waters was not the pursuit of new fish species. He was looking for eggs of the naked dragonfish as part of his work with Cheng and Arthur DeVries, also a professor of animal biology. DeVries and Cheng are known worldwide for their research on the built-in antifreeze protein that keeps these Antarctic fish from freezing in the icy waters.

This was Cziko's second visit to the McMurdo research station in Antarctica, which is saying a lot considering he received his bachelor's degree from LAS only three years ago. Cziko is heading off to grad school this coming fall; if he focuses on polar biology, he says there is a chance he will make another trip to McMurdo station.

Should he return, however, the odds of discovering another new species are against him. In the Antarctic, where fish are not as abundant or varied as the tropics, discovering a new species is a rare event.

"But it's great to find a new species because it shows we don't know everything about the world," Cziko says. "Even with all of the advances in science, there are still a lot of things we don't understand."