When Don Quixote mistook a windmill for a giant in the famous Spanish tale, he was facing the kind of quaint structure you see in postcards. But today’s windmills are true giants, with turbines reaching heights of 100 meters (328 feet), not counting their 100-meter-diameter rotor blades. When windmill turbines this big are clustered in massive groupings, they can affect temperature and humidity, so LAS researchers are studying locations where large-scale wind farms would have the least effect on weather.

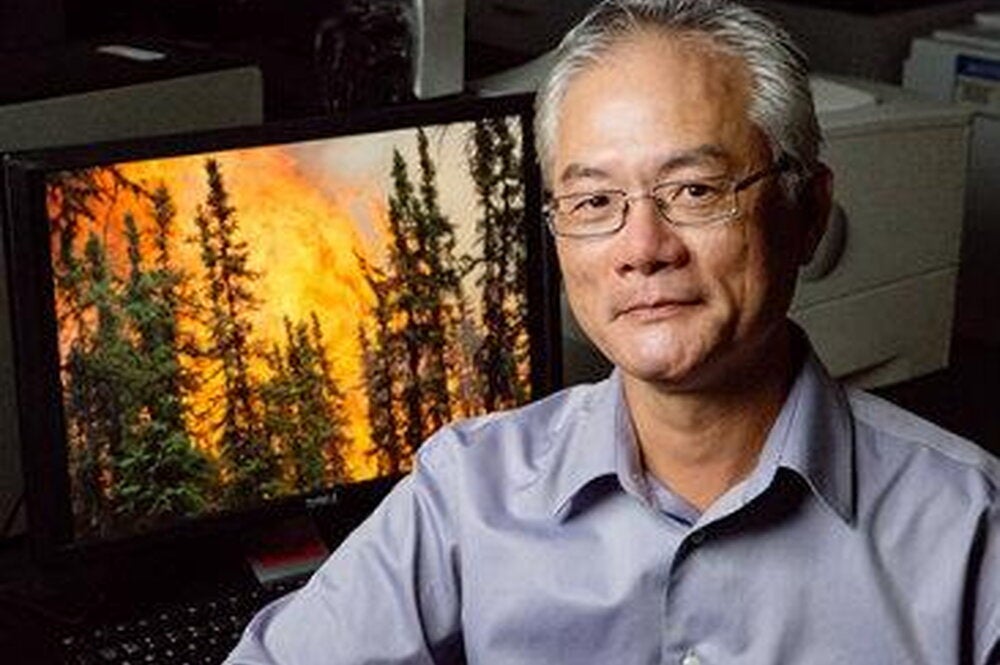

Looking worldwide, University of Illinois researchers have found that wind farms would have the least impact on weather in large parts of central and eastern Africa, western Australia, eastern China, southern Argentina and Chile, northern Amazonia, Greenland, eastern Canada, and the New England region in the United States, says Somnath Baidya Roy, U of I professor of atmospheric sciences.

In earlier work, published in 2004, Baidya Roy found that the large blades of a windmill create turbulence in their wake, much like the propeller of a boat in water. The turbulence caused by one turbine can disrupt airflow to nearby turbines, significantly reducing the efficiency of the wind farm.

In addition, the turbines mix upper level air with air near the surface of the ground, which can either raise or lower surface air temperature slightly, depending on conditions. If the upper level air is cooler than the surface air, this mixing will cool the surface temperature slightly; but if the upper level air is warmer than the surface air, the mixing will warm the surface temperature.

In most cases, the mixing will also reduce humidity because upper level air generally tends to be drier than the surface air.

Baidya Roy’s 2004 research, based on a huge hypothetical wind farm in Oklahoma (10,000 turbines), found air mixing in the summertime could increase surface temperatures by an average of 1.2 degrees Fahrenheit (0.7 Celsius) over the span of a day.

“To put this in perspective,” he says, “the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects a warming of 3.6 to 7.2 F (2 to 4 C) by the end of this century in the southern United States. Wind farms can slow down this warming by reducing the emission of greenhouse gases.”

Wind farms the size of the hypothetical one in his research project do not currently exist, but Baidya Roy says he is looking one step ahead into the future to anticipate impacts.

After analyzing the effect of wind turbines, Baidya Roy decided to look for ways that wind farms could have a low or possibly even zero impact on meteorological conditions. To do this, he looked for areas in the world that combine high wind energy and “high kinetic energy dissipation rates.”

Kinetic energy is the extra energy that something possesses because of its motion. Baidya Roy says that the kinetic energy in wind is naturally dissipated as heat, most of it near the surface. A windmill simply adds a step in the process by absorbing kinetic energy from the wind and converting it into electricity, then heat.

Therefore, if an area has a high dissipation rate, the windmill will fit into this natural cycle more efficiently and have less impact on the area’s weather.

Currently, Baidya Roy says the largest wind farms have hundreds of turbines, but he believes the 1,000-turbine mark will be crossed soon. He says a typical, large, coal-based plant operates at a 1 gigawatt scale; but to create a gigawatt-scale wind farm, you need several thousand turbines.

“If you want to make an impact on energy production, 500 to 600 turbines are not going to do much,” he says. “We need a huge amount of growth.”

Baidya Roy says the next step in his work is to examine specific regions in greater detail, rather than the entire globe, for the best locations for low-impact wind farms. He also recognizes that the impact on meteorology is just one of many considerations that go into a site. For instance, he found mountaintops and Antarctica to be good regions for low-impact wind energy, but sites need to be near transmission lines, preferably in areas where land is cheap.

According to Baidya Roy, the farmers with whom he has talked about wind power are enthusiastic because individual wind turbines leave relatively small footprints; they would take few acres out of production and would provide added income to farmers through land rental to power companies.

“I’m a big proponent of wind and solar, but they are not going to be solutions by themselves,” he says. “They will be part of a solution package.”