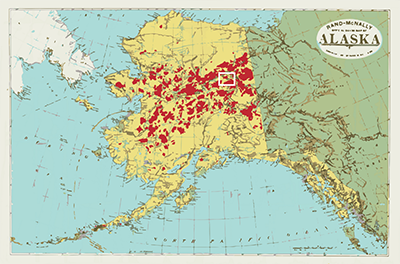

The forests in Alaska’s Yukon Flats are burning at a higher rate than any time in the last 10,000 years. A new analysis by researchers at Illinois finds that so many forest fires are occurring there that the area has become a net exporter of carbon to the atmosphere.

This is worrisome, because arctic and subarctic boreal forests like those of the Yukon Flats contain roughly one-third of the Earth’s terrestrial carbon stores. As climate warming increases forest fires, the researchers say, the conflagrations could release more carbon to the atmosphere and enhance warming.

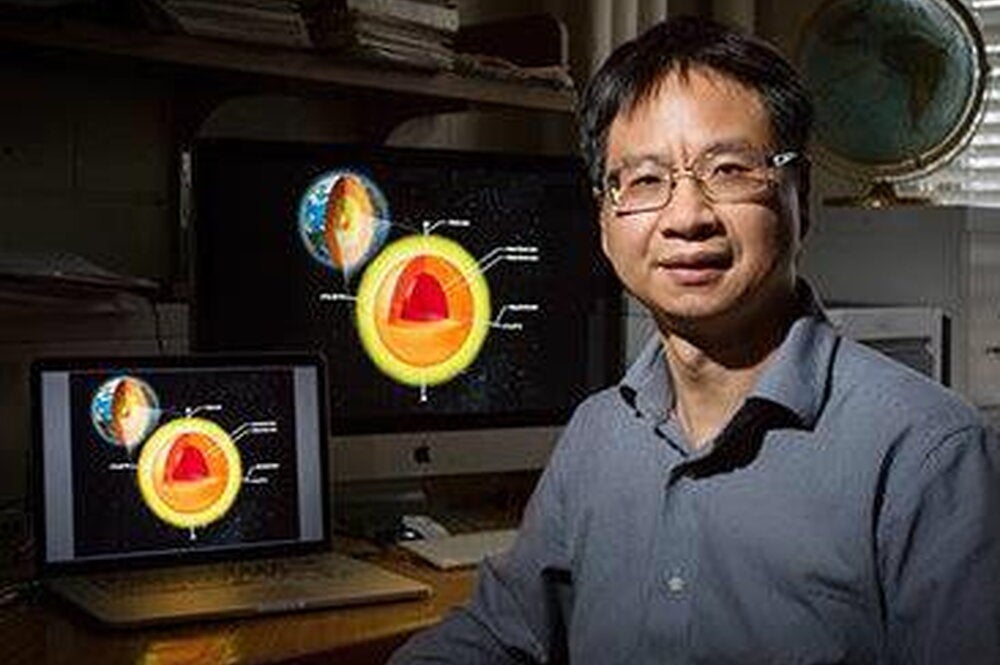

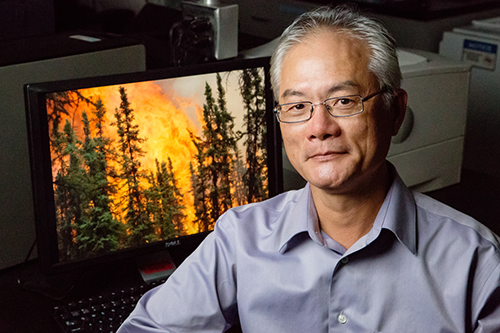

“Boreal forests contain vast carbon stocks that make them inherently big players in the global carbon cycle,” said Ryan Kelly, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois who conducted the study with Feng Sheng Hu, a U. of I. professor of plant biology and of geology. “And the main way that this stored carbon is eventually released is through fire.”

Alaska fire records go back only to 1939, and scientists often assume that present-day fire activity mirrors that of the ancient past. The researchers on the new study instead used actual fire data from a previous study in which they analyzed charcoal fragments preserved in lake sediments in the Yukon Flats. In that study, they found that fire frequency in a 2,000-kilometer swath of the Yukon Flats is higher today than at any time in the last 10,000 years.

“Our model confirms our hypothesis that the recent increase in fire frequency in our study region has caused massive carbon losses to the atmosphere. About 12 percent of the total stored carbon has been lost in the last half century,” said Kelly, who now is a data scientist and modeler for Neptune and Company, Inc.

“Most studies of carbon cycling in boreal forests have been motivated by the fact that there’s just an enormous amount of carbon in these high-latitude ecosystems,” Hu said. “Up to 30 percent of the earth’s terrestrial carbon is in that system. And, simultaneously, this region is warming up faster than any other parts of the world.”

Increasing numbers of fires are unbalancing the cycle of carbon capture and release, the researchers report. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could enhance plant growth, but it also contributes to further climate warming in the higher latitudes, Kelly said.

“Such warming would likely be attended by increased wildfire activity, which would more than cancel out plants’ carbon uptake and lead to a net increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide,” he said.

The new findings challenge studies that assume that recent fire activity reflects the norm over thousands of years. Those assumptions would lead scientists to conclude that the region has been a net carbon sink in recent decades, the researchers said.

Replacing that assumption with actual fire data from the past millennium offers a starkly different picture of the carbon cycle in the Yukon Flats, they said.

“The effects of forest fires on the carbon cycle are very dramatic. Fires explain about 80 percent of the change in carbon storage over the past millennium, and a large amount of carbon has been lost from this ecosystem because of increasing forest fires,” Hu said. “This area has burned more than any other place in the boreal forests of North America. We chose the area for this study because we thought it could be an early indicator of the future.”