A three-spined stickleback, a fish only about one-and-a-quarter inches long, slowly approaches a pike, an aggressive predator several feet in length. The stickleback swims within inches of the pike’s mouth, an audacious move for such a small fish. Meanwhile, in another part of the tank, another stickleback hides behind a plant, for it is not about to be caught out in the open with a killer in the vicinity.

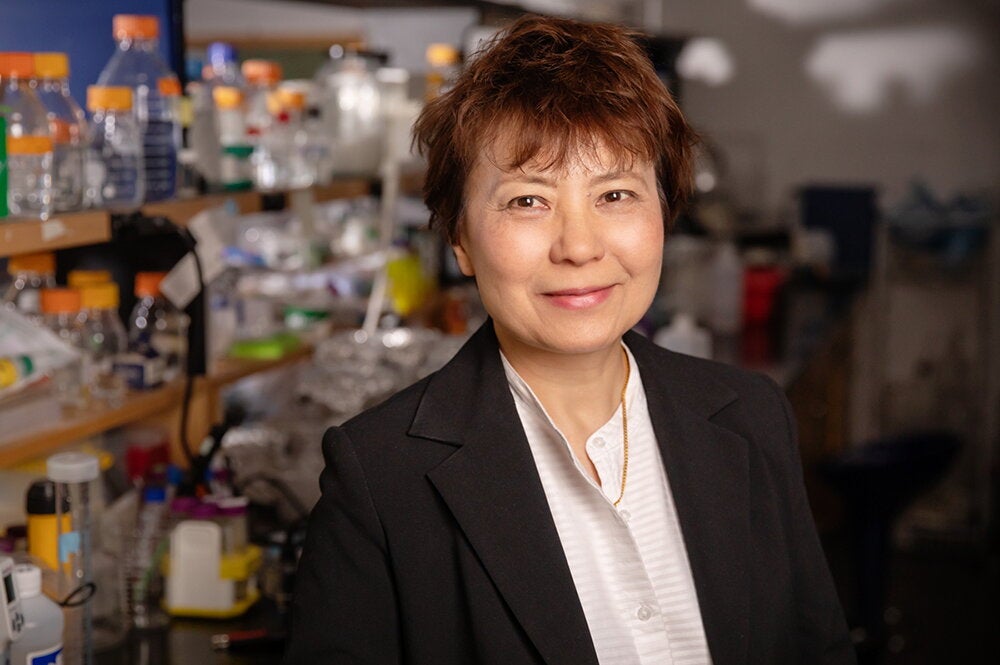

Neither fish is aware that the pike is not real; it is a model being used in the laboratory of Alison Bell, an LAS professor of animal biology. What is real, however, are the differences that Bell and her graduate researchers are finding in fish personalities.

But what does it mean to say that a fish has a personality? Having a personality means that an individual, whether you’re talking about a human or a fish, will behave differently than other individuals of the same species. Also, it will behave much the same way from day to day and week to week. “There is an element of consistency,” Bell says.

In the case of fish, Bell is looking at how different sticklebacks respond to predators—behavior that is crucial to small fish. After all, roughly 80 percent of juvenile sticklebacks will be eaten, so how they respond to predators is a matter of life and death.

Bell’s lab has discovered significant differences among sticklebacks, and she has found that individual fish are consistent in their behavior. The bold ones are consistently bold, and the timid ones are consistently timid.

Her team tracks individual fish in both the laboratory and in the wild, marking them with colored dyes as well as with colored “hats”—bits of plastic that they slip over a spine protruding from the back of a stickleback.

In one of the lab’s many experiments, sticklebacks are placed inside the dark, protective interior of a PVC pipe stuck in the middle of a store-bought kiddie pool. The only exit from the PVC pipe is a single hole, but it is plugged. After researchers remove the plug and open the exit, they time how long it takes for individual sticklebacks to have the courage to emerge from the pipe.

“Some sticklebacks immediately dart out, but other fish stay in the pipe for many minutes and ever-so-carefully peek their nose out, look around, and go back in,” she says. “Individuals are very consistent in their behavior. In fact, this is one of the most repeatable behaviors that I’ve ever studied. I’m amazed by it.”

What’s more, Bell says they have found that the same personality traits are manifested in different ways. For example, fish that act boldly in the presence of predators are also more aggressive around other male sticklebacks; and fish that are more cautious around predators are less aggressive around other sticklebacks.

Understanding behavior differences among fish can have ecological implications, Bell says, because these differences can affect such things as the dispersal patterns of invasive species. It also sheds light on the interplay between genetic and environmental influences on personality. Bell’s team is creating a map of the stickleback brain and identifying which genes might be related to personality variation. She estimates that about 10 percent of the personality variation is genetic.

Her team has also found that the stickleback behavior they observe in the lab is indicative of behavior in the wild.

“We’re excited because that was something we were concerned about,” she says. “Does what we’re measuring in the lab mean anything? Is it relevant to real fish in the wild? It turns out that it is.”