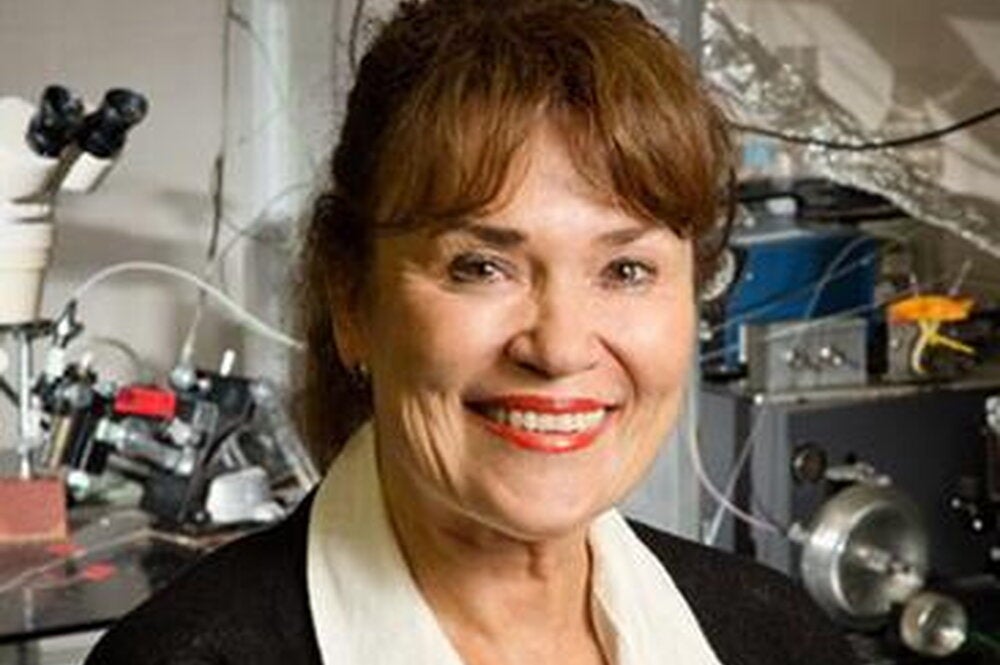

May Berenbaum still recalls how people would come up to her and ask her to sign their “Bambi Berenbaum” collector card from the popular sci-fi television show The X-Files. Bambi Berenbaum was the gorgeous X-Files entomologist that Agent Mulder took a fancy to, and she just happened to be named after May Berenbaum, the head of the University of Illinois Department of Entomology.

Berenbaum (May, not Bambi) responds to such distinctions with her trademark humor, for she has a knack for seeing both the humorous and serious sides of the world of insects. She founded the long-running Insect Fear Film Festival at the U of I on the one hand, but she has also emerged as a leading expert on colony collapse disorder, which has caused major losses of western honey bee hives.

Her abilities as both a communicator and researcher have earned her the 2011 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, the premier award for environmental science. The honor puts her in select company, for the prize has gone to such past recipients as biologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Edward O. Wilson, animal conservationist Jane Goodall, and conservation biologist Paul Ehrlich.

“Professor Berenbaum has done more to advance the field of entomology and explain the significance than nearly any other researcher today,” says Owen T. Lind, professor of biology at Baylor University and chair of the Tyler Prize executive committee. The Tyler Prize includes a $200,000 cash prize.

Berenbaum joined the U of I faculty in 1980 and has done groundbreaking research on how plants evolve to create natural defenses, such as chemical toxins to ward off pests, and how insects, in turn, evolve to overcome these defenses. Understanding this “arms race” between plants and insects has been fundamental to understanding pesticide resistance, insects, and genetically modified crops.

Research by Berenbaum has also shed light on the alarming disappearance of western honey bee colonies in North America since 2006.

“With roughly one-third of the U.S. diet dependent on one species of bee for pollination, it’s essential to understand what is happening to bees and correct course,” she says.

In addition to her research, Berenbaum has been a leading communicator about the lives of insects through many forms of media. In 1984, she founded the Insect Fear Film Festival, the popular annual event where she uses outlandish B movies about oversized insects threatening entire cities to drive home various entomological lessons. For instance, the 2011 festival in February focused on killer wasps and featured two movies—Swarmed and Monster from Green Hell. The latter movie tells the tale of a swarm of huge, monstrous wasps that live in a volcano in Africa, terrorizing the inhabitants of nearby villages.

Many of Berenbaum’s books bring entomology to a popular audience, and the titles alone reflect the humor and accessibility of her work—Buzzwords: A Scientist Muses on Sex, Bugs, and Rock’n Roll; Ninety-nine Gnats, Nits, and Nibblers; and her most recent book, a cookbook entitled Honey, I’m Homemade: Sweet Treats from the Beehive. Another one of her books, The Earwig’s Tail: A Modern Bestiary of Multi-Legged Legends, pops many modern myths surrounding insects, such as the belief that if an earwig crawls into your ear it can bore into your brain.

Berenbaum is always prepared to embrace even the most unlovable of insects. In a New York Times article, for example, she tells how she received a bed bug in the mail during her early years as a professor and “was so thrilled to see a live bed bug, I showed it off to every graduate student I ran into that day.”

While she recognizes that your average person would probably prefer that bed bugs and certain other insects would disappear from the face of the Earth, she says, “This world, this planet, would not function without insects. Our lives would be miserable without insects and people don’t realize that. Someone has got to stick up for the little guy.”