In Jules Verne’s 19th-century science-fiction classic, Journey to the Center of the Earth, explorers climb down volcanic tubes to reach the center of our planet. Along the way, they discover gigantic mushrooms and insects, a vast interior sea, and battling dinosaurs. Today, geophysicists do not spend much time worrying about dinosaurs as they study the inner earth, but they do face an equally formidable foe—monstrous amounts of data.

For the past 10 years, seismograms have been continually collecting data on the inner earth’s structure, and computing power has not been able to keep up. The primary way to get a handle on the astonishing amount of data has been with a supercomputer. But LAS statistics professor, Ping Ma, has found a way for scientists to analyze huge databases like this using an ordinary personal computer.

This work recently earned Ma the prestigious 2010 Faculty Early Career Development Award from the National Science Foundation (NSF)—a five-year grant for $400,000. The NSF has already been a strong supporter of Ma’s work, which could revolutionize the way researchers handle large databases.

“It’s still in the developmental stage, but we believe this powerful tool could eventually be used by most every researcher in their daily lives,” says Ma, who worked on the new statistical method with researchers at the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University.

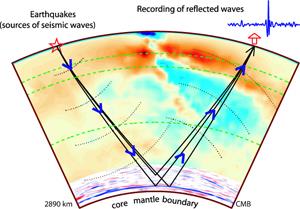

Even though Ma’s system is still in development, it has already been effective in proving the existence of the “D” layer, which is sandwiched between the outer core and the mantle deep within the Earth. The outer core is found 2,890 kilometers below the surface of the Earth, or 1,795 miles down.

Scientists cannot take direct samples deeper than about 93 miles, so geophysicists rely on other methods to create a picture of the Earth’s interior, and one of the primary ways is by analyzing seismic waves created by earthquakes. These waves bounce off of the different layers within the Earth, like light bouncing off of a mirror. By analyzing information carried by the waves, geophysicists can determine the location of layers and even the material that makes up a layer.

According to Ma, thousands of seismograms all across North America are constantly monitoring earthquake waves, and these sensitive instruments pick up earthquakes that humans cannot even notice—below 2.0 on the Richter scale.

The seismograms work nonstop, adding to the database daily. Researchers can analyze the information using a supercomputer, but that approach consumes large amounts of power, he says, and most scientists do not have access to a supercomputer.

“A supercomputer is a powerful tool, but there are big costs and many barriers,” Ma points out.

Therefore, he has found a way to take subsamples from the large database—subsamples that are representative of the larger database.

“Using this smaller data set, we perform the computing,” Ma says. “Our hope was that this small data set can perform similarly to the large database. And so far it’s working beautifully.”

During the next five years, Ma’s team will continue to refine the system. They are also using it with other large databases, such as the massive amounts of data being generated in genomics. In particular, they are using the subsampling system to analyze data from the genomes for humans, zebra fish, yeast, and archae (which is similar to bacteria).

Without these kinds of methods, he says, “we would be buried in a sea of data.”