“Every two seconds, an area of forest the size of a football field is clear-cut by illegal loggers around the globe,” says a World Bank report just released in March. The report went on to say that “forestry’s criminal justice system is broken. Despite compelling data and evidence showing that illegal logging is a worldwide epidemic, most forest crimes go undetected, unreported, or are ignored.”

In the face of this problem, Illinois research has found that one of the most effective ways to protect forests in developing countries has been by relying on the eyes and ears of the local population.

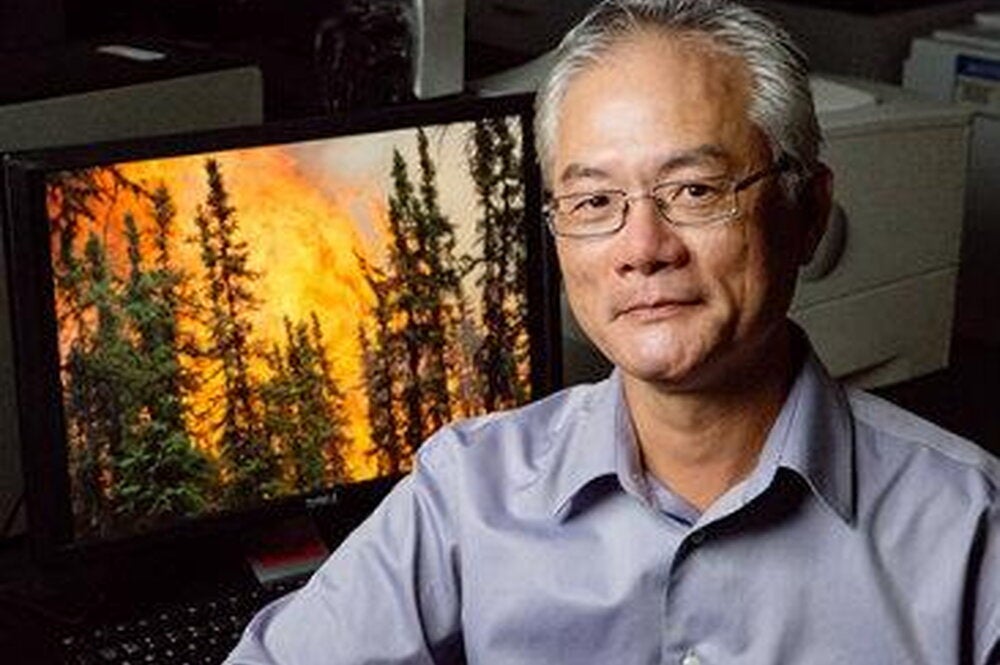

Historically, many governments in developing countries have tried to manage forests with inflexible rules that didn’t just target large-scale illegal loggers. The rules also made life difficult for the poor communities next to forests—communities that relied on the forests for their survival, either directly or indirectly, says University of Illinois geography and geographic information science professor Ashwini Chhatre.

But that is all changing, he says, thanks to a growing trend toward the decentralization of forest management in developing countries. In fact, Chhatre’s research has found that shifting the control of forest management from a centralized bureaucracy to those living next to the forest has not just helped the local people; it has also led to a comeback for forest cover in many places.

“People who live next to a forest know more about what is going on, both in terms of who is cutting trees down or what is happening inside the forest,” says Chhatre. “They have the most interest in making sure that bad things don’t happen to the forests in their backyard—especially forests on which they depend.”

Chhatre examined forest management trends in 10 developing countries, including Mexico, Kenya, Guatemala, and his home country of India. He says the decentralization of forest management has been occurring in many of these areas since the mid-1990s, and this change has coincided with an increase in forest cover.

Chhatre’s research has found that the two trends are linked.

India is a good example of this dramatic transition. He says the country reached its peak of deforestation in the mid-1970s, but forest management has since been decentralized and today trees in India are being regenerated faster than they are being cut down. Illinois research found that decentralization helps to drive this trend by giving local people more autonomy and power over “rule making.”

“In the past, bureaucracies in many developing countries made rules sitting in some capital city for all forests in the country,” he says. “But if you give the local people some power to make rules, they will be more involved in managing and protecting forests. It may be a headache for central bureaucracies to keep track of what’s going on throughout the country, but the outcome is usually better.”

Chhatre points out that forests offer many different benefits and services that need to be balanced. We want our forests to provide raw wood, sequester carbon, harbor endangered species, regulate the water cycle, and provide food to local communities, “especially in poor areas where people are quite dependent on forests.”

The problem is that centralized bureaucracies typically manage forests based on only one of these benefits. They might manage it solely for its raw wood, or they might manage it solely to protect endangered species. By shifting power to the local community, it is much easier to balance the benefits, meeting many different needs simultaneously, he says.

As one example, Chhatre says the decentralization of forests in some developing countries has made it permissible for people in nearby poor communities to gather and sell certain commodities from the forest, such as wild honey, natural rubber, medicinal plants, Brazil nuts, or mushrooms.

“These are sources of income for poor communities, if we only allow them to do that,” he says. “But under centralized bureaucracies, there was no flexibility that would allow a poor community to rely on the forest for food. Instead, they would spend enormous effort keeping the people out with guns and fences.

“But it didn’t make sense,” he adds. “You can’t have enough guns and enough fences to protect every tree—especially if you don’t have the local people on your side.”