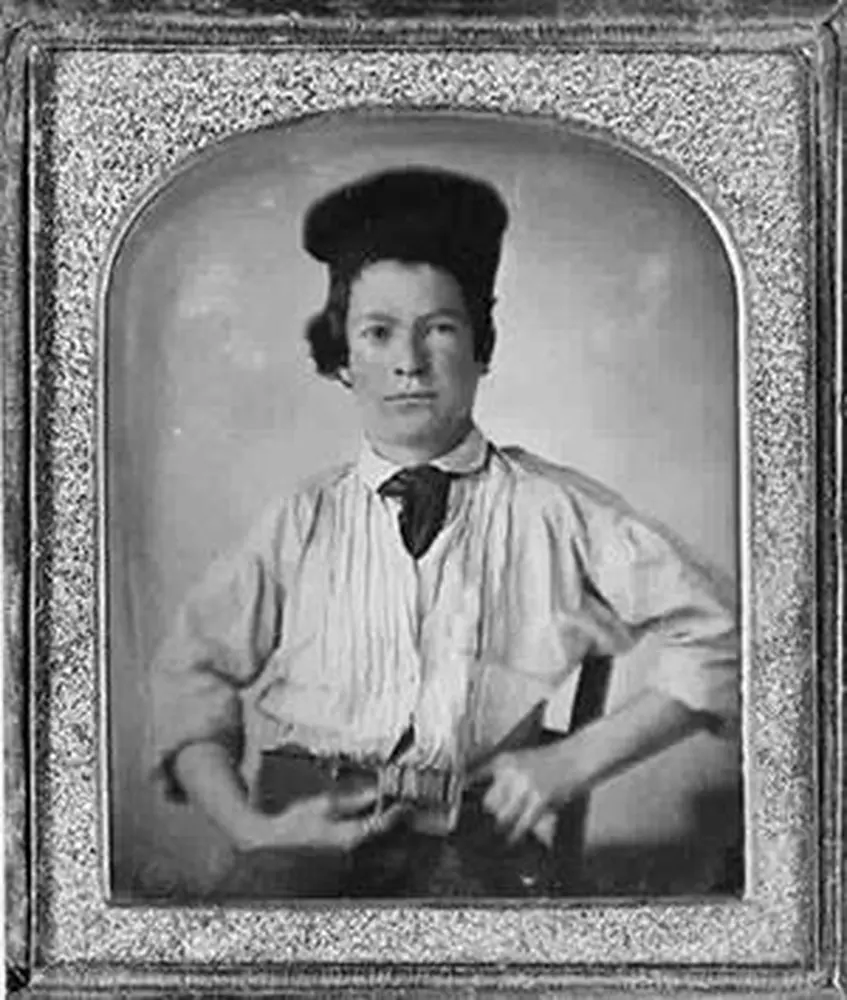

With his trademark cigar nested between two fingers, Mark Twain once strolled in broad daylight through the heart of London—in a blue bathrobe.

The stunt drew a crowd of curious onlookers, as Twain intended, but this wasn’t the first time the famed writer pushed the envelope with regard to his public image. On another occasion, he invited a throng of reporters to interview him at his home as he lounged in his bed in his PJs—cigar in hand, of course.

“Mark Twain had an impish, anarchic side,” says Bruce Michelson, a University of Illinois English professor emeritus who has spent much of his career studying Twain, the Lincoln of American literature. Michelson retired in 2013 after 37 years with the U of I, but he continues to write and talk about Twain—sometimes in unlikely places. With a Fulbright Award for the spring of 2014, he has been lecturing in Belgium, where he says, “Twain is surprisingly iconic.”

Interest in Twain has risen worldwide since the publication of the first two volumes of Twain’s autobiography in 2010 and 2013. The first book was expected to sell only about 7,000 copies, mostly to libraries and scholars. Instead, it went to the top of the best-seller lists, selling close to a million.

Twain would probably have loved the attention, for Michelson says the writer sought press coverage with an aggressiveness that would fit right into today’s media-saturated world. For example, Twain would time his Sunday carriage rides down New York’s Park Avenue for the hour when crowds of people were leaving church, causing a stir as they saw him pass by. As a stage performer, he loved to take risks with audiences: long silences, strange glares, and double-takes, all to keep them off balance and laughing, and to keep the papers stirred up about his strangeness.

“He loved any sort of front-page news about himself,” says Michelson, who has written two books on Twain and spent 17 years as director of the U of I Campus Honors Program. Michelson speculates that if Twain were alive today, “It’s hard not to believe he would be tweeting like a madman. He would be blogging; he would be all over YouTube. In fact he is all over YouTube—and he’s been dead for over a century.”

The durability of Twain is what first drew Michelson to the writer whose real name was Samuel Clemens. “Twain has been hard to push back into the same shelf-landscape of other famous long-dead American authors,” he says. “He was the first writer to achieve an illusion of deep intimacy with everybody. One of the advertising slogans tossed around about him was ‘Known to Everyone, Liked by All.’ He really worked at that connection, and it holds to this day.”

According to Michelson, “The fun of studying Twain is that his life reads like a big, rambunctious, American novel. He didn’t speak to you wisely from a condition of privilege and insight, like George Bernard Shaw or Oscar Wilde. He wrote and spoke as a common man.”

However, he could also be uncommonly difficult. “He was a mercurial, difficult, and explosive man to work with,” Michelson says, and he drove his nephew Charles L. Webster to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Twain put Webster in charge of his publishing company, which had early success with Ulysses S. Grant’s massive-selling memoir. After that, Sam Clemens expanded the company’s operations headlong, scolding and second-guessing Webster and eventually driving the house into bankruptcy.

Clemens had a knack for losing money, says Michelson. In addition to the failed publishing company, he sank the equivalent of millions into the Paige Compositor, a revolutionary typesetting machine with 16,000 moving parts.

“When the machine worked, there was nothing like it for elegance and completeness in putting together justified type,” Michelson says. “The problem was that it hardly ever worked. Twain was brilliant at putting his money on the wrong horse.”

Although Twain looms large in Michelson’s career, the LAS professor has also written and taught about other writers, including Oscar Wilde, Tom Stoppard, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Edith Wharton. In addition, he is president of the American Humor Studies Association and past president of the Mark Twain Circle of America.

But not everything is humor-driven for Michelson. He has also written extensively about the American poet Richard Wilbur, whom he calls “an antidote to Twain’s impulsiveness, messiness, and contradictions. Wilbur’s poetry is polished intensity; he’s a quiet stoic of sustained attention.”

Nevertheless, Twain remains at the forefront of Michelson’s work, and the professor is currently writing his third book about Twain’s impact on American life.

“Twain is a writer who stands at the intersection of so many large-scale issues in American culture and American literature,” he says. “In the 100-plus years since his death, he’s been repainted and refloated as the political eras have changed. For instance, when we needed him as a Civil Rights icon in the 1960s, he was there.

“If you want Mark Twain as a moral hero, you can have him that way,” he adds. “If you want him as a huckster and ruthless, gilded-age capitalist, you can have him that way. As feminist, yes. As sexist, yes. The trove is big enough and varied enough that you can go in and find any Sam Clemens you want.”