Computers and quantitative analysis have revolutionized the study of science. What can they do for the study of literature? Investigators have high hopes as a new multi-institutional partnership involving the University of Illinois turns to big data to better understand the vast history of novels and what they say about society.

Applying data-crunching computer power to the study of novels could allow literary historians to answer questions previously too large to answer, says Ted Underwood, professor of English at the U of I, who is one of 10 literary historians leading the project, called Text Mining the Novel: Establishing the Foundations of a New Discipline.

The University is one of several collaborators on the project (http://novel-tm.ca), which originated at McGill University after it received a nearly $2 million grant from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The U of I’s Institute for Computing in Humanities, Arts, and Social Science, along with the National Center for Supercomputer Applications, are also partners on the project.

“A lot of what we’ve done in the past in English departments is focusing on 30- to 50-year spans of time, or movements or periods such as Romanticism and Modernism,” Underwood says. “We’ve found it harder to generalize about long-term trends, because frankly they’re harder to deal with, harder to get a grasp on. I think one of the ways computers are going to change the humanities is to make it easier to back up a bit and see the big picture trends.”

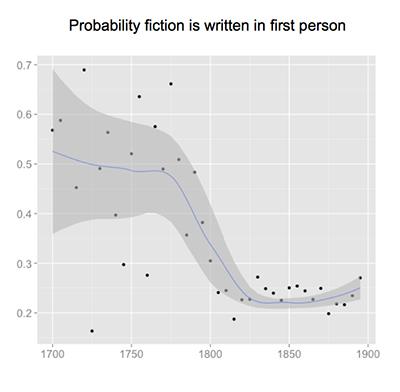

“Text mining” refers to the study of the millions of books that are available at digitized repositories such as Google Books or Hathitrust Research Center (of which U of I is a partner). With that amount of literature quickly available, researchers say they can answer the big picture questions, such as: “How did introspective thought begin appearing in novels?” and “How did the language of novels deviate from the language of poetry?”

As for questions of the 20th century, Underwood adds, “there’s a good distinction between literary fiction and genre fiction, like romances and science fiction. What’s the story there? Can we trace that separation? Can we see it happening on the quantitative level, with the diction and language used in different genres? Does that give us any insight on how genres differentiate, or why they differentiated?”

These are tantalizing questions to literary historians. The problem, however, is that the digitized repositories are virtual mountains of information. Analyzing it requires skill in computer science and quantitative analysis and knowledge of literature. While text mining isn’t quite the scale of, say, the Large Hadron Collider, Underwood says, “it’s terabytes of data and days of processing time.”

Underwood says that much of the six-year grant will be spent on training graduate students in English to analyze digitized text and will pay for the computer processing involved in making sense of the information that’s gathered. Right now, he adds, much of the quantitative study of literature is being done by psychologists or computer scientists because they have the skills. (“I don’t want them to completely take over,” Underwood says with a laugh.)

Indeed, analyzing the data will require plenty of knowledge of literature gained through traditional English courses. For example, Underwood says, someone crunching the raw numbers on novels might notice increased references to money during the 19th century. A literary historian, however, realizes that it may have less to do with changing attitudes and more to do with the fact that publishers began including advertising sections in the back of the book.

Underwood is in his third or fourth year of applying this kind of analysis to novels, but he is more excited than ever about the grant and the possibilities it presents.

“I have done a lot of traditional literary work in my career, but it’s a lot of fun to have something completely new that really stretches you,” he says. “And the quantitative methods coming out of computer science right now are coming out of these traditions of artificial intelligence capable of identifying patterns. So I may apply a learning algorithm to gothic novels, and say, ‘What patterns do you see there? What do they have in common?’ It’s an algorithm that not only sees what’s there, but finds evidence of a general pattern. That’s really interesting.”