During the mid-1990s, with images of starving children in North Korea seared into Byung-Ho Chung’s mind, he met with a North Korean official to offer a shipment of anti-parasitic drugs that could help fight malnutrition. The official brusquely refused.

“We do not have such a dirty problem in our republic,” the official told Chung. Undeterred, Chung changed tack, and during the next meeting he called the drug a “nutrition enhancer.” The North Korean official broke into a wide smile.

“Of course we can receive this kind of drug,” the official said, even as Chung was certain he knew the drug was the same.

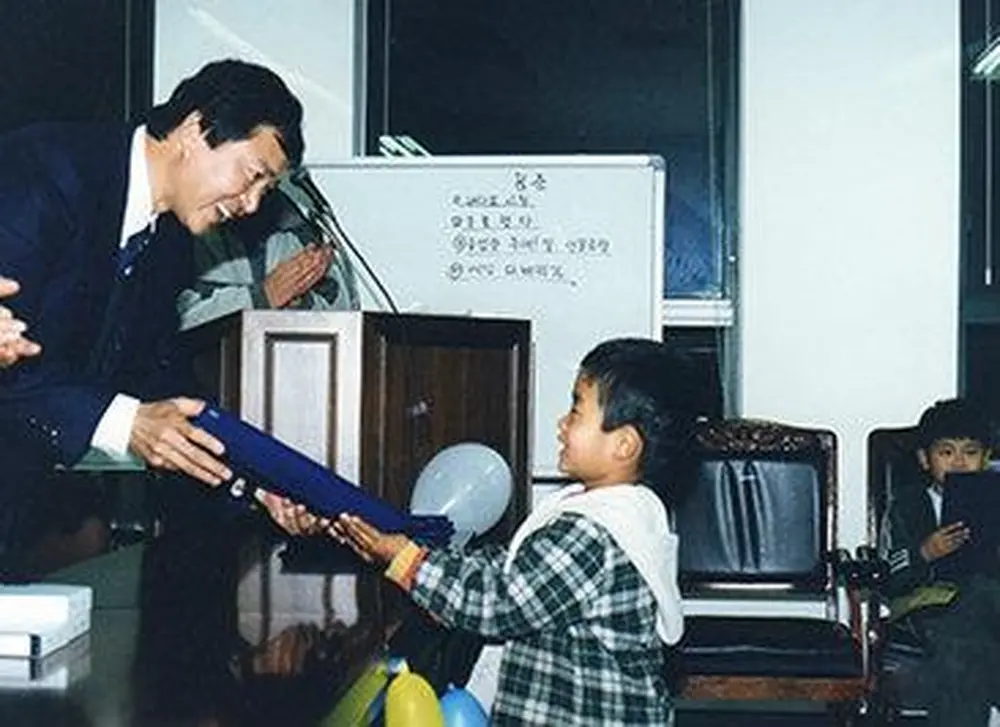

It’s one lesson of many that Chung (MA, ’83, PhD, ’92, anthropology) has learned during some 20 years of relief work on the Korean Peninsula, which he addressed during a recent trip back to the University of Illinois to receive the 2014 Madhuri and Jagdish N. Sheth International Alumni Award for Exceptional Achievement.

Chung, 59, a South Korean native, leads a dual life: One as a professor of cultural anthropology at Hanyang University in Korea, where he founded the Institute for Globalization and Multicultural Studies, and the other as an activist, having founded six social justice organizations focused on fostering multiculturalism and peace between North and South Korea. His work for North Korean refugees earned him the nickname “Dr. OK” by children, for whom he has been an encouraging and easygoing force.

In accepting the award at Alice Campbell Alumni Center, Chung reflected on everything from the influence of the University of Illinois on his ideas, to dealing with the “cold-blooded” bureaucracies of both North and South Korea as he tried to deliver aid and other assistance. The most gripping moment was his video of North Korean children during the 1990s, their faces gaunt from famine, marching on stage and singing in perfect unison that they were “happy.”

Indeed, Chung painted the picture of a relatively straightforward relief mission complicated by decades of suspicion, pride, and politics. Relations improved between the North and South between 2000 and 2008, Chung said, but since then he says the South Korean government has taken a tougher stance toward its neighbor, and it’s become harder to deliver supplies north of the border.

”Surrounding the borders of North Korea, we are talking a totally different level of irrational realities because of the political hatred,“ he said.

Chung’s studies of North Korea (in particular, his 2012 book, North Korea: Beyond Charismatic Politics, a study of North Korean leadership which he co-authored) have led him recently to step back from dealing directly with North Korean officials, as he worries that they may resent what he’s written and complicate his aid efforts.

He’s remained active behind the scenes at his organizations, however, while believing that his dual role of scholar/activist is more important than ever.

“Activism can easily stagnate, easily become falsified, (and become a) self-oriented organization without some elaboration, and analysis, and some creation of new paradigms,” Chung said. “I think my role as scholar and anthropologist is to stimulate the organization effort, and also provide new paradigms in the changing situation.”