In 559 B.C., the leader of the Rong barbarians in China argued that his people should be regarded as equals to those from the northern state of Jin. As the barbarian leader made his argument, he suddenly began to chant “Blue Flies,” a poetic ode about the dangers of slander.

This story appears in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture, and it illustrates how poetry often played a crucial role in political diplomacy in ancient China. Today, it would be as if Secretary of State John Kerry suddenly began reciting poetry as part of his negotiations with a foreign leader.

The long tradition of poetry and literature in China lies at the core of the new journal, which is the brainchild of Zong-qi Cai, LAS professor of Chinese and comparative literature. The Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture released its first issue (a double issue) in November of 2014, bringing together top scholars from both China and the West.

Prior to the publication of this new journal, “There was only one journal devoted mostly, but not exclusively, to premodern Chinese studies and it was launched about 40 years ago,” Cai says. “We needed a new approach.”

Cai’s new approach is a “global vision,” he says, because the journal attempts to unite Western scholars on premodern Chinese literature with researchers in China who use traditional scholarship methods going back thousands of years. With this global impact in mind, it is a joint effort between the University of Illinois and Peking University, which is considered “China’s Harvard.”

“We need to break down the boundary between the two cultures and draw on each other’s strengths,” Cai says.

The Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture is published in English, but Cai has also started a sister journal published in Chinese—The Lingnan Journal of Chinese Studies. The Lingnan Journal was once one of the top scholarly journals in China from the 1930s through the early 1950s. But because Lingnan University was run by Christians, it was forced to disband in 1953. Today, the university has been reborn as the Lingnan University of Hong Kong, and Cai has helped them to revive the journal.

The two new journals—one in English, the other in Chinese—will have a far-reaching impact on both Chinese and Western scholars of premodern (before 1900) Chinese literature and poetry, Cai says.

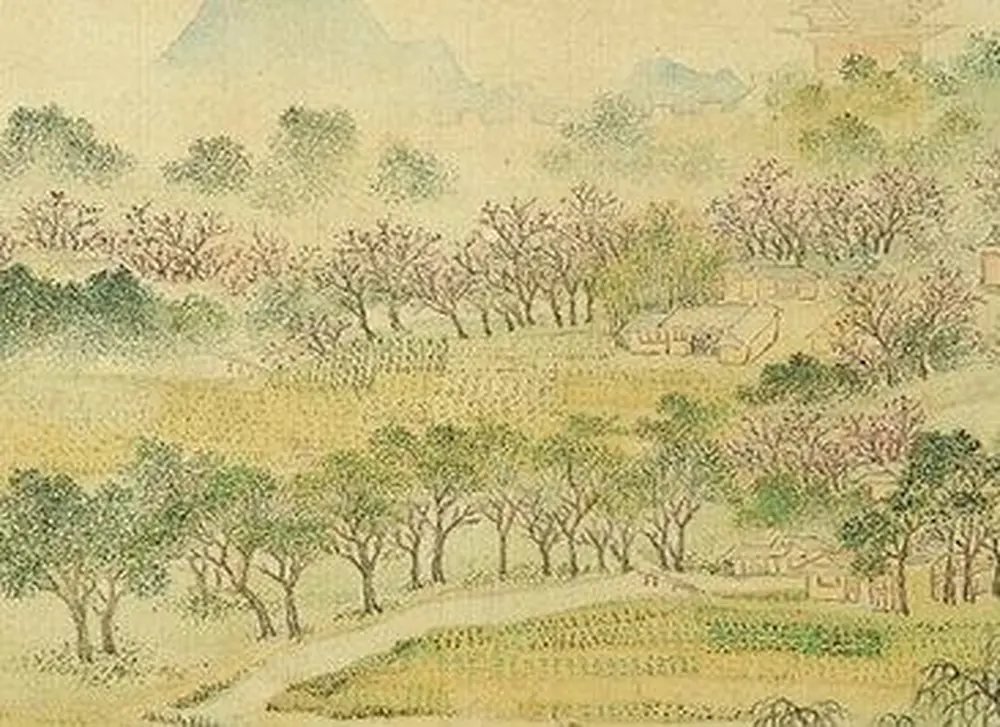

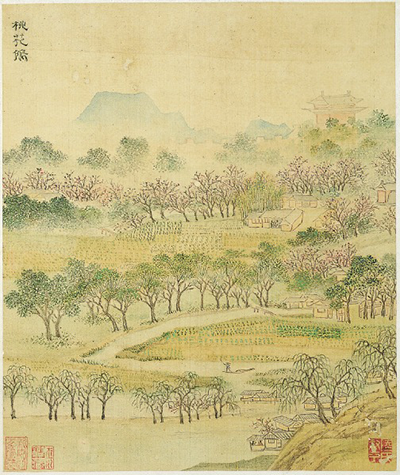

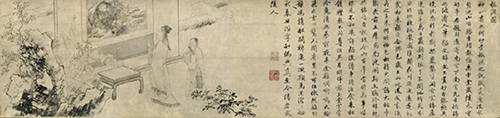

The Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture is being published twice a year, and it will alternate between general-subject issues and special-themed issues, such as one on Chinese literature and visual culture, which will include 40 full-color plates of ancient art.

“It will be a feast for the eyes,” Cai says.

The journal is divided into three major area: Chinese culture; terms, concepts, and methods; and text matters. The section on culture reveals the ties between literature and various aspects of Chinese culture, such as the lute or the game of a Go, a form of chess in which the goal is to encircle your opponent’s pieces.

The section on “terms, concepts, and methods” is important, Cai says, because Chinese literary terms are “polysemous”—one term can have multiple meanings. This section will explain how to sort through the many meanings of various words. Finally, the “text matters” section will delve into ancient Chinese texts, which are continually being uncovered, some written on ancient silk or bamboo.

Although the journal is a joint effort of the U of I and Peking University, it is being published by Duke University and is gaining an online presence through Project Muse, a leading provider of digital material in the humanities and social sciences. Cai also started a website that ties both of the new journals together—the Forum on Chinese Poetic Culture.

Cai, who was born in Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton), came to Illinois in 1993, and he credits LAS with making The Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture possible by providing critical support for research assistants.

Cai says that the study of premodern Chinese literature remains a preeminent scholarly pursuit in China, but in the West it is being overshadowed by modern Chinese literary studies.

“In the West, the field of premodern Chinese literature studies, particularly classical poetry, has dramatically shifted from the very center of scholarship to the margins,” and that’s why these journals are so important, he says.

“The old form has a long life,” Cai adds. “It’s a continuing, living tradition.”