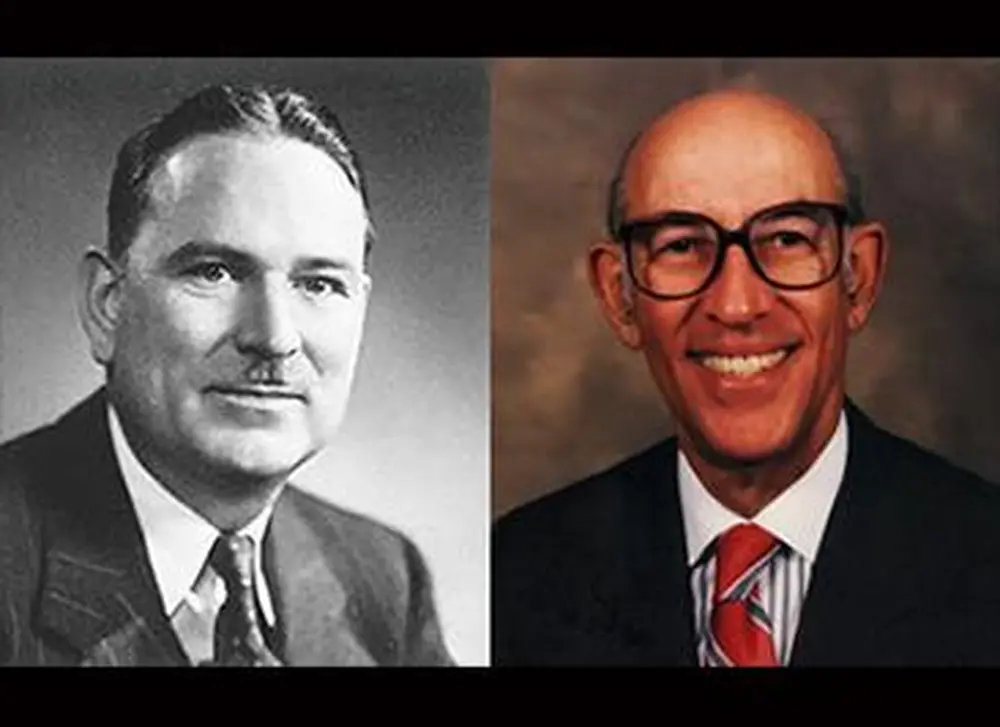

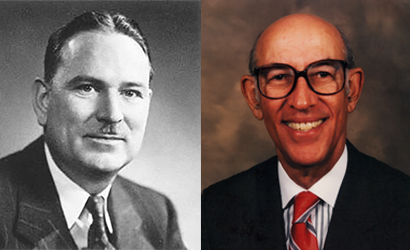

A pair of LAS alumni responsible for momentous breakthroughs in science will be formally inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in a ceremony next week.

The late William Sparks (PhD, chemistry,’36) AND the late Welton Taylor (BA, ’41, MS, ’47, and PhD, ’48, bacteriology) were among 16 inductees recently admitted to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, located in Alexandria, Va.

Taylor (1919-2012) is remembered for his lifesaving advances in microbiology, particularly in regards to food poisoning. After a salmonella outbreak in baby food at Smith & Company, where Taylor worked, he and his colleague, John H. Silliker (who was also inducted to the Hall of Fame), developed a highly accurate method to test egg yolks for salmonella that’s still used today.

Sparks (1905-1976) had 145 patents to his name, but he’s best known for co-inventing poly-isobutylene-co-isoprene, more commonly known as butyl rubber, while conducting research at Standard Oil Company in 1937. Butyl rubber was critical to keeping the U.S. and its allies supplied with tires, rafts, boots, and other products during World War II when Japanese warships cut off shipments of natural rubber.

His co-inventor, the late Robert Thomas, was also among the 16 inductees recently admitted to the Hall of Fame.

The 2016 inductees will be honored at the National Inventors Hall of Fame Ceremony on May 4-5. The first day will feature an illumination ceremony at the Hall of Fame, located in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office campus in Alexandria, Va. The official induction ceremony will take place the following day in Washington, D.C.

Taylor was globally renowned for his work, which included developing rapid and effective methods for identifying three type of bacteria—not only salmonellae—that cause food poisoning. His methods were eventually adopted by health care officials worldwide to prevent food poisoning in processed food.

His four patents and some 40 publications “formed the basis for further microbiological and bacteriological progress, and continue to influence bacteriologists and microbiologists today,” the Hall of Fame noted in its biography of Taylor. He taught at the medical schools of both the University of Illinois and Northwestern University, and he was named microbiology-in-chief at Chicago’s Children’s Memorial Hospital, according to his obituary for the Tuskegee Airmen, of which he was a member. He was a consulting microbiologist at a dozen other Chicago-area hospitals.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention named the bacteria Enterobacter taylorae in honor of Taylor and his colleague, Joan Taylor (no relation).

Taylor received the U of I President’s Medallion in 2007 as a member of the Chicago “DODO” chapter of Tuskegee Airmen, who fought in World War II as the first African-American aviators in the U.S. military. Taylor wrote a memoir, Two Steps from Glory, detailing his experiences in the war and also his experiences at U of I before and after the conflict. His daughter, Karyn Taylor, said that her father helped to integrate the U of I campus in Urbana-Champaign while living as a graduate student in veteran’s housing in the 1940s.

“So often, the geniuses who work behind the scenes to make the world a safer place rarely get the recognition or visibility they deserve,” Karyn Taylor said. “But thanks to the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame, the world will now know our father’s name and know that Welton I. Taylor dedicated his life to ensuring that millions of people the world over can eat dinner every night without being poisoned by bacteria they can’t even see. His was a monumental accomplishment and we couldn’t be more pleased.”

The induction of Sparks also has special significance on campus with his grandson, Robert Sparks, now attending Illinois as a doctoral student in biochemistry. Robert recalls how his grandfather tested car emissions by placing a sock over a tailpipe, and how he tried to sell the president of Exxon (earlier called Standard Oil and Esso) on geothermal energy.

“He was very concerned about the environment,” Robert said, adding that his grandfather’s favorite quote was “Science without purpose is an art without responsibility.”

According to the Hall of Fame, Sparks and Thomas invented butyl rubber while experimenting with another Standard Oil product called Vistanex. They combined it with a small amount of butadiene in a washing machine.

“Smoke fill the air as the spin cycle finished, revealing the pair’s first commercial batch of butyl rubber,” the Hall of Fame reported. Butyl rubber turned out to be as strong as natural rubber, resistant to oxidation, and possessing unusually low gas permeability. Beside its use in World War II, it was commercialized in 1943.

Butyl rubber’s qualities make it useful for protective gloves, sealants, adhesives, tire inner tubes, bladders in sporting balls, and more. It’s good for dampening vibrations, exhibits good flexibility, resists weathering effects, and can become quite cold without becoming brittle.

Some of Sparks’ other patents included new fuels, gasoline additives, propellants, encapsulated oxidants, asphalt additives, and food-wrapping films.

There are several connections between the Sparks family and Illinois. Robert’s father, who earned a degree in biochemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was taught by the son of Carl Shipp “Speed” Marvel, an Illinois professor who was considered one of the world’s most outstanding organic chemists. Marvel was Williams Sparks’ doctoral advisor.

Robert’s grandmother—Meredith, the wife of William—earned a doctoral degree in organic chemistry at Illinois under Roger Adams, for whom Roger Adams Laboratory is named.

Others from Illinois who have been inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame include the late Arnold Beckman, (BS, ’22, chemical engineering, and MS, ’23, physical chemistry), for inventing the pH meter, and the late Paul Lauterbur, Illinois professor of chemistry, who won the Nobel Prize in 2003 for his pioneering work in the development of magnetic resonance imaging.