Natural selection—that merciless weeder-outer of biological designs that are out of step with the times—also is a wily shaper of traits. Exhibit A is the pointy murre egg, according to new research published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Common murres and thick-billed murres tend to nest in tightly packed colonies on craggy seaside cliffs. The ledges on which they lay their eggs can be quite narrow, sometimes “as shallow as the egg is long,” the authors of the new study wrote.

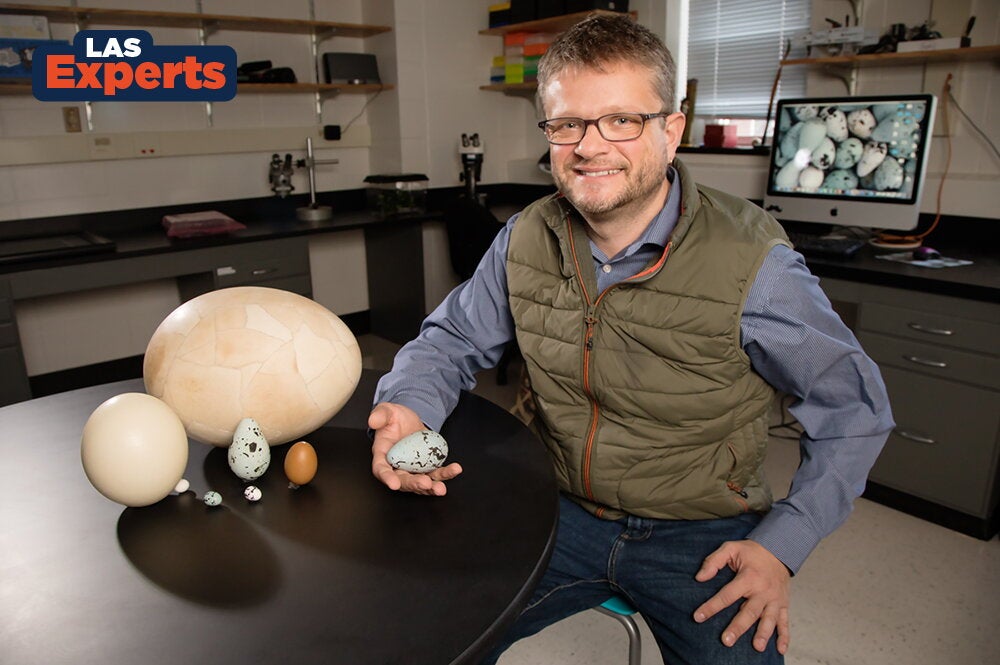

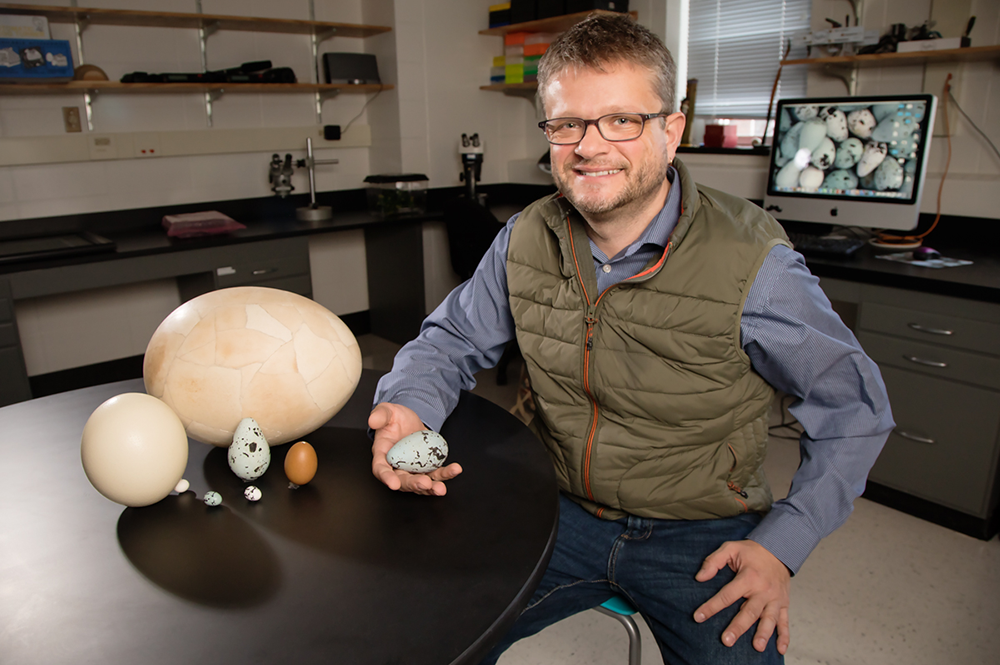

“Very little is known about how the murre egg shape affects its stability and viability in this setting,” said Mark Hauber, professor of animal biology and the Harley Jones Van Cleave Professor in the School of Integrative Biology who conducted the study with former Hunter College graduate student Ian Hays. Many have theorized that the shape makes the eggs less likely to roll off of cliff ledges, he said. “But earlier studies failed to isolate specific features of the eggs – such as elongation, asymmetry and conicality – to robustly test this hypothesis.”

To put the theory to the test, Hauber and Hays turned to a 3D printer that can manufacture fake eggs in a variety of shapes and sizes. By altering individual shape variables and testing them singly or in combination in an “egg-roll” test, the researchers were able to determine which factors were most likely

to keep the egg from straying far from its original position.

“We found that conicality—the degree to which the pointed end of the egg mimicked a cone—suppressed egg displacement on surfaces inclined more than 2 degrees,” Hauber said. At lower inclines, however, conicality only mildly increased egg displacement.

Increasing the length of the egg relative to its girth increased its tendency to roll further from its original position, the researchers found. And, as the distance from the fattest part of the egg to the narrow end increased relative to its overall length, so did its tendency to roll.

“In general, an egg’s conicality was the most reliable predictor of its likelihood of staying put on inclined surfaces,” Hauber said. “This finding provides experimental support for natural selection shaping the unique form of murre eggs amongst all bird eggs.”