Going from teaching in front of an auditorium that seats 600 students to lecturing on a webcam at home requires patience and skill – and, for one professor, a lot of imagination.

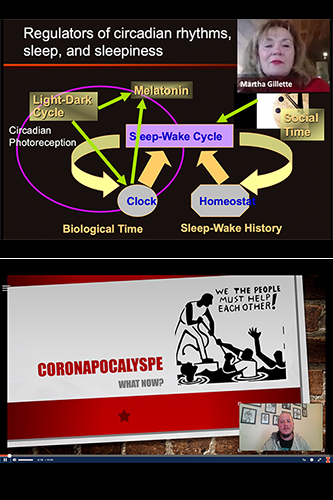

Martha Gillette, professor of cell and developmental biology and director of the Neuroscience Program, co-teaches a class on integrative neuroscience and learned a way to maintain her energy now that she’s just talking to a computer screen.

"I have to imagine that my students are in front of me in order to give an animated and engaging lecture," Gillette said.

To slow the spread of COVID-19, the University of Illinois, along with most other academic institutions around the country, has transitioned completely to remote learning until the pandemic subsides. It has been a learning experience for everyone; one professor in the Department of Political Science conducted an informal survey and found that about 75 percent of students had never used Zoom before.

Many professors, such as Gillette, are reporting that the transition has been successful or adequate. Gillette said her class transitioned well to Zoom with assistance of Katya Gribkova, her tech-savvy teaching assistant. She’s found that her students are just as engaged in the virtual classroom as they are in person.

“We had 94 people come to the lecture” in the integrative neuroscience course, Gillette said. “That’s more students than come to most lectures in Lincoln Hall. We were so thrilled.”

With every trial, there’s also error; for Gillette, this meant adapting to online testing platforms and listening to students’ input.

“We were one of the first classes to give an exam,” she said. “Students said they didn’t like being video monitored by their computer while they took it, so we decided to give an open note exam.”

Ninety-four students took the exam in real time, and the one person who didn’t was flying to Korea. They took the exam after landing without any technical difficulties.

These numbers for the online exam were about the same or better than normal in a couple of ways. During a normal exam, Gillette said, they typically administer about six makeup exams, as opposed to the single makeup exam for the online version. The student performance on the online exam was about the same as in-person testing, Gillette said.

“I’m working harder than I would normally during the school year,” Gillette said. “But we’re here for the students. We want them to feel accommodated.”

Billy Huff, a lecturer in the Department of Communication, sent his students a survey to assess their online access and availability, as well as their preferences regarding course delivery methods.

“It was their feedback that dictated the decisions I made in the transitions,” Huff said.

He teaches CMN 323: Argumentation and CMN 250: Social Movement Communication, which he said are easily relatable to the current pandemic.

“I have been able to create video lectures with accompanying PowerPoint presentations using Kaltura for Argumentation that use examples drawn exclusively from media that covers COVID-19,” he said. “Students are experiencing the urgency of media literacy and having the ability to critically examine the arguments that surround them.”

Because of the pandemic, Huff’s Social Movement Communication students can directly apply what they're learning to the outside world. This includes spreading messages that highlight people who need help the most – such as those who are unemployed, those with low socioeconomic status, or those without health insurance.

“(Students) are certainly experiencing the communication advantages of using social media to organize, but they are also experiencing the frustrations and drawbacks that accompany a lack of face-to-face interaction,” Huff said. “I am profoundly proud of them for innovating and creating new ways of using communication technologies to create solidarity and support among Illini students.”

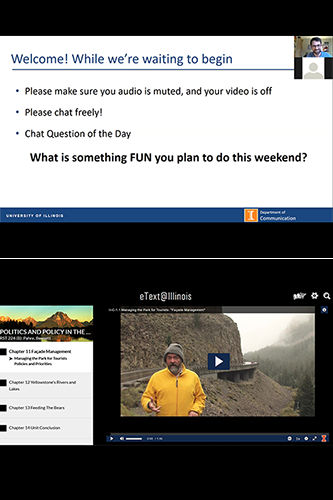

Robert Pahre, professor of political science, said that when the pandemic closed campus over spring break, they decided to offer PS 224: Politics of the Greater Yellowstone Area. That’s a previously established online course based on eText, a course platform developed by the Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning (CITL). The course relies on many hours of video that was filmed in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

CITL helped set up the course on no notice over the break, and Pahre has been leading the course as teaching assistants were already booked with other courses.

“It's a good lesson in why our portfolio should include well-designed online courses,” Pahre said.

Pahre has always done assessment of his non-traditional courses, both online and field studies. Along with a CITL team led by Maryalice Wu, an adjunct assistant professor with the Department of Sociology, he’s conducting a study titled “Tracking Student Engagement in an Online Course.” They have tentatively found, for example, that in comparison to traditional lecture courses, his online course with embedded video has better emotional engagement with students than lecture courses.

Pahre jokingly calls this the David Attenborough effect, as people are connecting emotionally with material in video documentaries. He adds, however, that lectures, seminars, field trips, and online courses each do some things better than others, and some worse.

In contrast to the Yellowstone course, he worries that video conferencing from home presents a new host of potential schedule conflicts.

“Students have been thrown into family and social situations that mean they may not be available for that 9:30 a.m. class anymore,” he said. And while Pahre thinks that polished video lectures work well for online learning, he adds that “instructors need to think about how to break the material into manageable pieces, too."

William Barley, professor of communication, has also applied the subject matter of his lectures to the coronavirus. His class, CMN 410: Workplace Communication Technology, focuses on how communication technologies are designed, implemented, adopted, and used within and across organizations.

“During in-person lecture, we had been talking about the diffusion of innovations and how technologies spread throughout diffusion curves,” Barley said. Then, suddenly, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic put the concept of diffusion curves in a new light. Barley helped his students apply what they’d learned about technology diffusion to interpret the phrase “flattening the curve” in regards to the coronavirus.

In their final in-person class before campus shut down, Barley’s class covered research-proven techniques for implementing technologies in organizations. Ironically, they soon found themselves having to implement new technologies to stay in touch while everyone moved off campus.

Barley is using Zoom for his lectures. He redesigned this particular course, however, to allow students to have a voice in determining how the class would be run online. His first lecture topic after the class moved online was the most important, given the situation: What’s the best way to use Zoom?

“We’re in uncharted territory,” Barley said. “I planned on continuing lecturing like normal on Zoom, but then I said, ‘Wait, if you expect things to go on as normally, then you don’t have room for challenges.'"