In an unusual study, researchers brought vampire bats from distant Panamanian populations together for four months in a laboratory setting and tracked how the bats’ gut microbes changed over time. They found that bats that interacted closely with one another shared much more than body heat.

Reported in the journal Biology Letters, the study revealed that the gut microbiomes of bats became more similar the more often they engaged in social behaviors with one another. Such behaviors included huddling together for warmth, grooming themselves and their neighbors, and – in rare cases – sharing food via regurgitation.

This is the first study of social microbiomes to control for other factors – such as diet and environment – that could contribute to microbiome similarities, the researchers said. The study kept all the bats together in one enclosure and the bats consumed the same, laboratory-prepared food: cattle and pig blood.

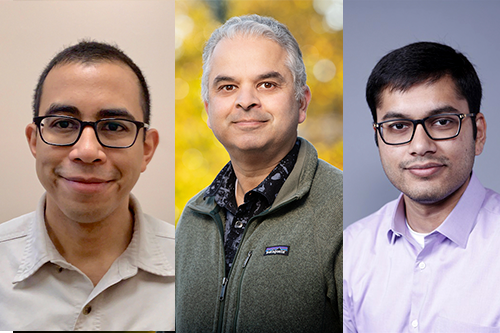

“Vampire bats cluster together for warmth, and they groom themselves quite a lot, so their saliva is already all over them,” said Gerald Carter, a professor of evolution, ecology, and organismal biology at Ohio State University, who conducted the research with Karthik Yarlagadda, a former PhD candidate studying biological anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and U of I anthropology professor Ripan Malhi.

“They’re spending about 5 percent of their awake time grooming each other, licking the fur and bodies of other bats,” Carter said. “They also share food sometimes, but it’s a rare behavior.”

“The ‘social microbiome’ – defined as the collective microbial community of an animal social network – can fundamentally shape the costs and benefits of group living,” the researchers wrote.

Click here to watch videos by Carter of bats in a cave, or a captive-born bat feeding on a live animal for the first time.

Microbes that make their homes on the skin or in the digestive tracts of animals can be beneficial or pathogenic to the individual and to the community. Understanding how such microbes are transmitted and shared within groups can help scientists devise strategies to promote the benefits and reduce the dangers associated with microbe sharing in various populations, said Yarlagadda, who led the microbiome work.

“Vampire bats have these really interesting social behaviors, and their diet is very controlled because they only consume blood,” he said. “So vampire bats are a natural model to explore the relationship between their social behaviors and their microbiomes.”

To better understand this dynamic, Yarlagadda compared the patterns of microbiome variation within – and between – the different groups that were housed together.

“We saw that the microbiomes of bats that regularly engaged with one another socially became more similar to one another,” he said. “When bats interacted less – even if they came from the same population initially – their microbiomes were less similar by the end of the four months.”

The work is important because it adds to the understanding of how social microbiomes develop and change, and because vampire bats sometimes carry rabies and can spread it to humans and livestock, Carter said.

“Vampire bats are a main reservoir for bovine rabies,” Carter said. “It’s a problem for agricultural development throughout Latin America and it’s a public health problem.”

Understanding how microbes are transmitted in these animals may help scientists find interventions to reduce the spread of pathogens like rabies, he said.

Malhi also is a professor in the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the U of I. Yarlagadda is an analyst in the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service. The National Science Foundation, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Animal Behavior Society supported this research.