By the turn of the 20th century the residents of east-central Illinois had learned a few hard facts about the environment, and one of them was this: Once you chase away the squirrels they almost never come back. Nevertheless, in 1901, the University of Illinois launched a plan to return the long-lost tree-dwellers to campus.

To appreciate the magnitude of the plan, consider what had been lost. Forget what you think qualifies as a lot of squirrels; gray squirrel populations in the Midwest during the mid-1800s were “truly astonishing,” according to a 1978 study by the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS), with hunters capable of claiming hundreds per day. By 1900, however, due to hunting and the clearing of virgin forests, the arboreal grays were virtually absent from Illinois.

They weren’t forgotten by geology professor Charles Rolfe, however, who, besides being prominent in clay and groundwater research, would also earn the nickname of squirrel master. In May 1901 he proposed a plan to President Andrew Draper to bring a few dozen squirrels to campus, put them in breeding cages, and complete an unlikely faunal comeback.

Draper “heartily approved” and successfully pitched the $250 plan to the Board of Trustees.

“If successful, the influence upon university life, and upon the feelings of students, would be considerable, and students would carry that influence to all parts of the state,” Draper said.

It’s hard to know when Draper and Rolfe realized that they were over their heads, but the plan was plagued with setbacks from the start. Imported squirrels died in their shipping containers before arriving. Many that survived the trip died of disease or disappeared. Local residents started shooting them.

“(Grounds superintendent) Fred Atkinson tells me hunters are all over the premises almost every day, Sundays included,” Rolfe wrote to Draper in December 1901. “We shall certainly lose some squirrels if this is not stopped.”

Alarmed, the university and local community mobilized to action. The cities of Urbana and Champaign passed ordinances making it illegal to kill or wound a squirrel, punishable with fines of $3-$10.

Unfortunately, the new laws meant nothing to one of the squirrels’ most ancient enemies: dogs. Rolfe reported that dogs were raiding campus for squirrels, prompting Draper to write a stern order to groundskeepers. The Daily Illini later called it a kill order, which may or may not have been an overinterpretation of the president’s word choice.

“I notice a number of dogs about the campus,” Draper wrote. “People owning them should be notified to take care of them, or we will.”

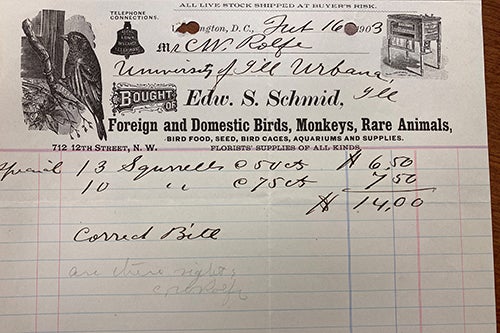

The odds facing the squirrel experiment, however, remained steep and sometimes inexplicable. In one case the university purchased two dozen squirrels from a supplier in Washington, D.C., at a price of 50-75 cents each (about $17-$25 in today’s dollars). Many of them died mysteriously after being released into a stand of evergreens.

Draper, who had met with the squirrel supplier during a trip to Washington, was exasperated, having promised the business office that it would be the last squirrel-related expense.

“We certainly can (pay) no further expense in this matter. I have gone so far already as to be embarrassed about it,” Draper wrote to Rolfe. “I am not sure (that) the pine trees are killing them.”

A few months later, in October 1903, Rolfe made a last-ditch effort to save the project, suggesting that he knew a trapper in Ohio who could supply squirrels at a reasonable price. By then, however, Draper was near the end of his term as president, and the squirrel experiment had taken its toll. No more squirrels were purchased.

“I am thoroughly discredited in the business office because of the squirrel matter already,” Draper wrote.

There’s little mention of the squirrel experiment after Draper’s successor, Edmund James, arrived in 1904. Perhaps a hands-off approach worked, however, because it soon became clear that squirrels had survived and even begun to thrive. Today, INHS reports that they travel easily between campus and surrounding habitats.

“We don’t have any indicators that the population is unstable or in any peril,” said Eric Schauber, principal research scientist and director of INHS. Added Ed Heske, a former adjunct professor of biology and mammalian ecologist at INHS, “I don't know if there have been other introductions of grays to (Champaign-Urbana)… but that introduction on campus about 120 years ago was super successful.”

In fact, in 1919, during an historic rise in student enrollment, the Daily Illini mused that the squirrels had become tied to the fortunes of the university itself.

“We wonder if the increased registration,” the paper wrote, “has anything to do with the increase in the number of squirrels flitting about the campus.”

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of The Quadrangle.