The largest and longest-lasting society formed by people who escaped slavery and their descendants endured for a century in northeastern Brazil, and it continues to be a potent political symbol of Black pride today. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign history professor Marc Hertzman wrote about the settlement and how memories of it survive in his book, “After Palmares: Diaspora, Inheritance, and the Afterlives of Zumbi.”

The first enslaved Africans arrived in Brazil in the 16th century, nearly 100 years before the U.S. slave trade began. Some escaped and established societies in an area known as Palmares, in the wilderness in northeastern Brazil. The settlements grew to at least 10,000 people, ending only after the Palmares leader Zumbi was killed in 1695.

Hertzman said he wanted to learn how the memory of Zumbi and Palmares survived from 1695 to the present and what it means today.

The book has five thematic sections, four of which focus on the history of Palmares and its aftermath in the 18th century. The final section considers how Palmares and Zumbi became contested symbols of national identity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Zumbi is a symbol of Black pride in Brazil, and some areas celebrate the date of his death, Nov. 20, as a day to recognize the story of Black resistance. But there are questions about who Zumbi was, how he died and whether the name refers to one man or a series of leaders, Hertzman said.

“Zumbi is a really powerful symbol of resistance and also a flash point for reactionary responses,” he said.

No written records by the settlers of Palmares exist. The only records available came from those on the outside who wanted to destroy the settlement, Hertzman said, and what happened to Palmares and Zumbi is full of speculation. For example, many soldiers from that time claimed that they killed Zumbi before he actually died, most likely to collect a financial reward.

Zumbi’s assassination in 1695 is considered the end of Palmares, but people continued to live in the settlements and the fighting continued for decades, Hertzman said.

“It was like a 100-year war,” he said. “The Dutch tried to destroy them, then the Portuguese. The most powerful European empires were trying to destroy them, and they couldn’t. In one of the really remarkable chapters in Palmares’ history, the king of Portugal, through intermediaries in Brazil, offered a peace treaty. For all intents and purposes, settlers in Palmares were on equal footing with a European power.”

Hertzman traced thousands of people from Palmares and made educated guesses about what happened to them. While researching newspaper stories and land titles, he found places hundreds of miles away from the Palmares area that were named “Zumbi.” Some were given that name in the early 18th century, potentially by people who fled Palmares.

“A handful seem to clearly have some connection. People from Palmares were almost certainly there in the aftermath and the naming was around the end of Palmares,” he said.

Brazil was engaged in a larger percentage of the transatlantic slave trade than anywhere else, with 40% of enslaved people brought to Brazil, compared with about 5% to the U.S., Hertzman said. Slavery ended in Brazil in 1888, later than anywhere else in the Americas, and the country has more people of African descent than anywhere else outside of Africa, he said.

In 1988, Brazil approved a new constitution that recognized communities that can prove historical land possession and trace their descendance from groups who suffered racial oppression. The constitution provides small amounts of reparations. But many communities don’t meet the legal requirements for recognition, Hertzman said.

“After the splintering of Palmares, people went to various places and a lot of lineages can’t be traced back in the way the law lays out, but their stories pass through the same history. I think of Palmares as not ending but living on in ways that are hard to trace,” he said.

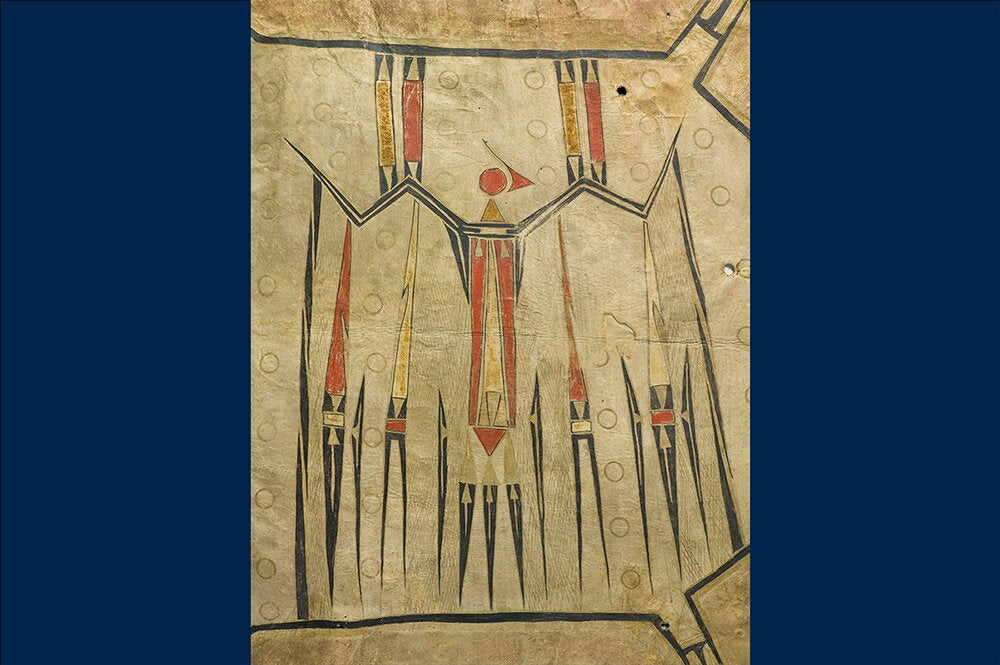

The legacy of Palmares includes such things as ways of naming the land, religion and the reclamation of the political symbol of Zumbi, he said.

Hertzman said he hopes the book helps add a new perspective to conversations about reparations in the U.S. and what it means to reckon with slavery — and will provide an opportunity to think about various possible versions of history.

“We can reconsider what we can know as historians. People were told that after Zumbi died, the story of Palmares was over. I want people to know there is a story afterward and to think about other histories that we think we can’t get at,” he said. “For people to know there was this place that was created and preserved against all odds is a really amazing story.”