As the weather begins to chill in the later days of October, leaves of warm hues fall from the trees around the Main Quad. Today is a pleasant day, though, and many are out enjoying it. One student sits outside Lincoln Hall with a sage-green philosophy textbook. It’s his first semester back at the University of Illinois after years away. He’d acquired this book before he left, but now he has time to really explore the teachings of Plato, DesCartes, Hume, and Kant held within the pages.

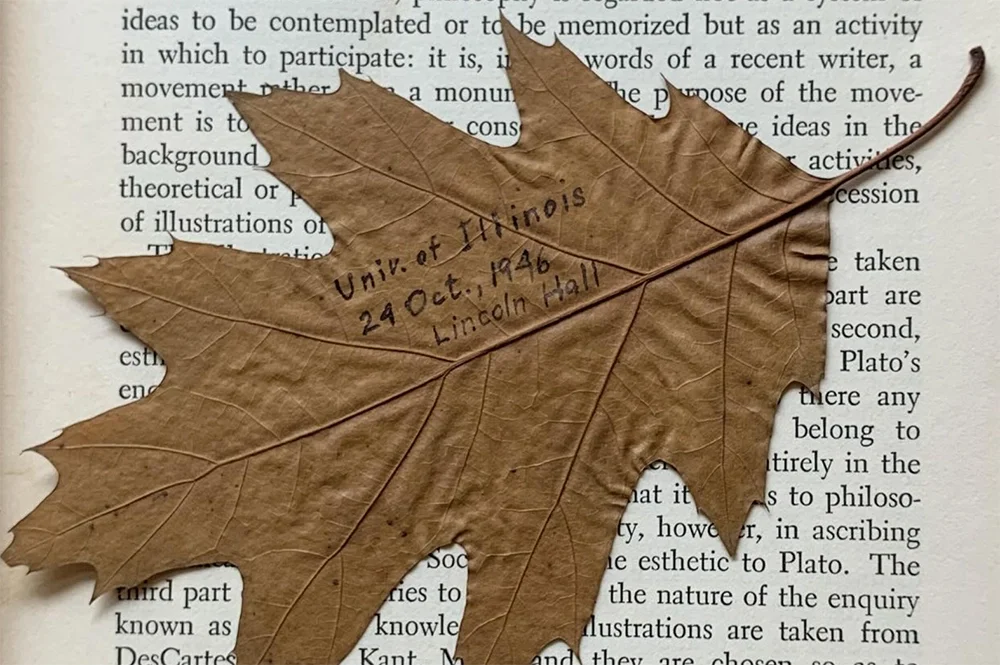

Something catches his eye from above. Against a cloudy sky, a brown oak leaf flutters to the ground. He picks it up. For some reason that can only truly be known to himself, he writes the following lines on the leaf:

Univ. of Illinois

24 Oct., 1946

Lincoln Hall

Tucking the leaf inside, he closes the book. Nearly 80 years later, in 2025, the leaf sees the light of day again when the book is opened by a vintage collector in Erie, Pa.

I would be remiss to not inform you that the scene I just described is speculative, built entirely from three clues: a textbook, a leaf, and a collector. If you enjoy a scavenger hunt through the past, walk with me.

A textbook, a leaf, and a collector

This all began with acculturation specialist Dana Filsinger of Brooklyn, N.Y., who found the sage-green philosophy textbook with the leaf at an antique shop in Erie.

“When I opened the book and found the leaf, it felt a bit surreal,” Filsinger said.

Filsinger shared photos of the textbook and leaf on her Instagram, calling it one of her favorite finds. The post eventually caught the attention of the College of LAS at U of I. My colleague, Ella Dame, interviewed her.

“It really makes you think about the things you have and who you are,” Filsinger explained. “One day, will someone be walking through my own estate sale? What interests do I have in my life, and what would I leave behind?”

Through antique collecting, Filsinger preserves the memories from people of the past. Curious to find the backstory of the book and leaf, Filsinger began researching the name signed on the front page of the textbook: Lawrence S. Monroe, Feb. 1942.

What she found was an obituary. Monroe (BS, ’48, mechanical engineering) passed away in Erie 18 years ago. The obituary provided many details about his life: He graduated from the University of Illinois, worked as a mechanical engineer, received numerous patents for surgical and medical equipment, and loved reading, swimming, and woodcarving. He was also a World War II U.S. Navy aviator veteran.

Though the handwriting on the front page differs from the handwriting on the leaf, the fact that Monroe passed away in Erie, the same place this book was found, makes me fairly confident he maintained possession of the book from obtaining it in 1942 to his death in 2007, making him the most likely person to have written on the leaf.

After Filsinger’s initial research, much of Monroe’s life — particularly his time at the university — remained a mystery.

Challenge accepted.

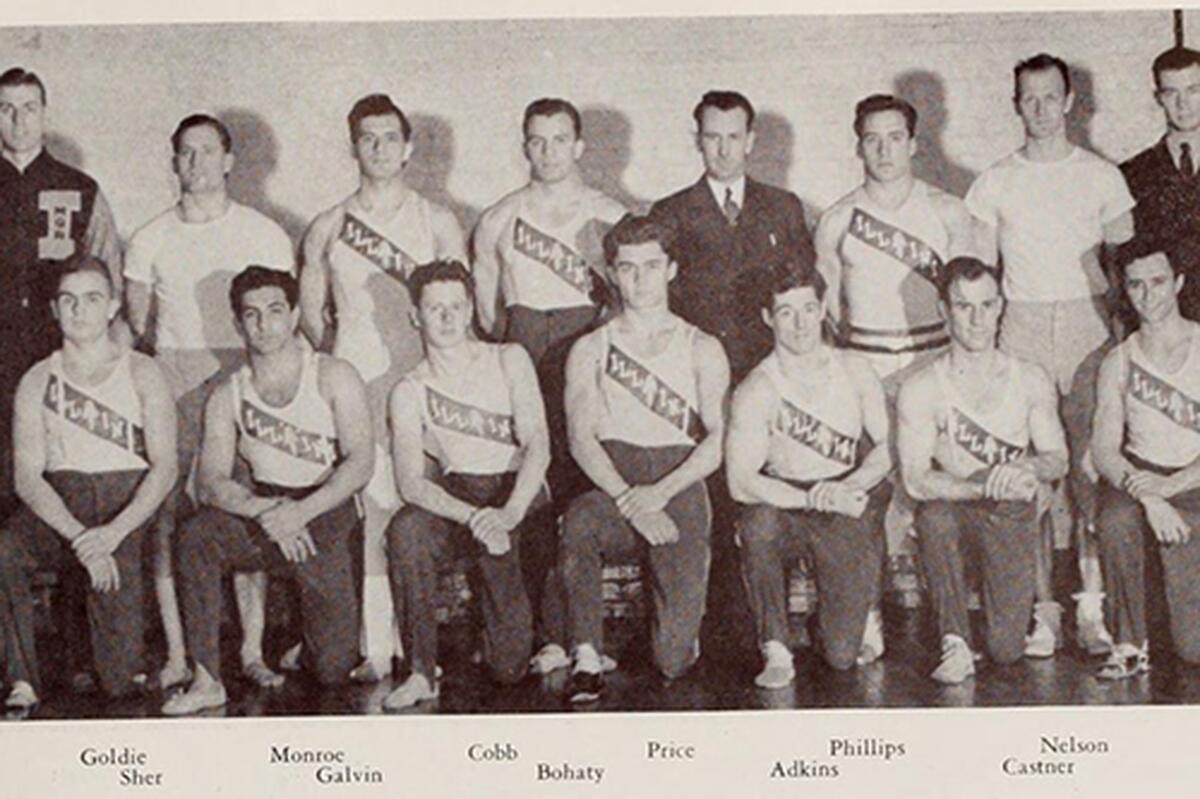

Though my search for Monroe’s living relatives left me empty-handed, I was confident the university’s extensive archives could provide insight into his time here. I began with the Illio yearbook from 1942. Sure enough, Lawrence S. Monroe was there. He was a member of the men’s gymnastics team, which reigned as NCAA champions for the third year in a row. He was also in Delta Sigma Phi.

Delta Sigma Phi lists him as a sophomore for the 1941-1942 school year. Judging by the date on the front page, Monroe acquired the philosophy textbook in that spring semester. For the next three yearbooks, Monroe is absent.

Perhaps he quit gymnastics and left the fraternity, I thought to myself as I screenshotted where his name should have been in the indexes and added that to my notes. Then, the years clicked.

Monroe is far from the only young man missing from the school yearbooks in the mid ‘40s. In fact, the campus was only 20% men at that time, as opposed to 75% in years prior. He’s missing because he served in the U.S. Navy in World War II.

When I learned about World War II in school, it always seemed so distant — stories told through black-and-white photos and grainy film. The generation that lived through that time was passing on as I was growing up. I was two years old when Monroe passed away.

Part of this disconnect is also due to how history is presented. I can give you statistics like 20,276 people from the U of I fought in World War II, and 738 were killed. Those figures are important, but they don’t help me to see through the eyes of students on a war-changed campus. I needed to get personal.

I have a deep fascination with mundane moments. When I look at history, I like to build scenes with as much detail as I can find so I can close my eyes and think about what I would do if I was there and then. What was it like to walk past the military training on your way to class? What was it like to plan meals while on sugar rations? What was it like to study for exams with the fear of war looming? What was it like to carry on after the war, knowing how many people didn’t make it back?

I’m a 21-year-old living in 2025. I type this story on a computer, connected to WiFi, while sitting in an air-conditioned room and streaming piano covers from the Internet through my cell phone connected to bluetooth headphones. If Monroe from 1946 heard me read that sentence, he would probably think I’m crazy.

But there is one thing that connects us: this campus. This book and leaf were an invitation to this mundane little moment outside Lincoln Hall 80 years ago. So, I set off to scour archived news articles, yearbooks, history papers, and even historical weather data, all to rebuild this moment.

Philosophy, gymnastics, and Larry Monroe

Let’s go back to the textbook. Personally, I do not think the leaf was simply a bookmark. Why would someone record the date and location for a bookmark? The leaf was found pressed between pages, a method used for preserving plants. This was documentation, preserving a moment.

Nowadays, it’s quite easy to track down a book via Internet search. I found the sage-green textbook: “An Introductory Course in Philosophy” by U of I professor John A. Nicholson, published in 1939. Why bother finding the book? Like I said, that leaf was made to document a moment. I wondered if something within the philosophy textbook could have provoked Monroe. In the short online preview, I could see the first few pages included references to World War I. How interesting, I thought, that someone supposedly reading about philosophy and war in such a time might wish to record and preserve a moment of peace.

To get myself a copy, I entered the trove of old tomes — the Main Stacks. Entering the Stacks feels like you’re crossing into another dimension. As you pass through the threshold, you leave the bright, bustling common area and enter into the dim, quiet liminal space containing rows upon rows of knowledge. It is frozen in time. When I spotted the sage-green textbook and pulled it from the shelf, I wondered when it had last been opened.

As for Monroe, he appeared several times in the Daily Illini throughout the 1940s. The earliest instance was the Delta Sigma Phi pledge list in September 1941.

His next mention is in an article dated Nov. 29, 1941, discussing gymnastics coach Hartley Price’s thoughts on how the war draft may impact the team.

“‘The draft has not bothered us to any great extent and although there is a drive on to stop us by legislation we should be able to turn out a well-rounded team,’” Hartley is quoted saying.

The article goes on to list the returning team members, including Larry Monroe and Lou Fina. Based on other articles and yearbooks, Fina was a remarkable gymnast. He is also, according to the article, “the only team member of this select group who will be drafted in February.”

But a lot happened between November and February.

“Thunderous and Deafening and Unbelievable”

“October of 1941 came and was amber, with lazy smoke and leaves too thick for wading, and war was far, and crowds thronged Memorial stadium. And November of 1941 was frosts and exquisite twilight, quiet and slow and hallowed, and warm lamps glowed in black, cold night, and no one knew, or wanted to know.

“And then, early that afternoon in December of 1941 something came from the Pacific that was thunderous and deafening and unbelievable, jarring and stirring and feverishly maddening. No, not here, not anymore on this world, not to this nation. It couldn’t happen.”

That excerpt comes from former Daily Illini sports editor and Pfc. Fritz Jaunch, who wrote a reflective column in the July 25, 1945, edition of the Daily Illini. Here, he recounts the blissful naivety around campus in the months leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor and even in the immediate aftermath.

“We were still joking. … And when the president of the University told the student body that classes would go on as scheduled the following morning, some of us wanted to know, ‘What good’s a war if we don’t get a day off.’

“It took us a while to know what had happened, to emerge from our dream, our make believe. It took us nights of bewilderment and days of sudden all-enfolding aloneness.

“... And then it was there, and we knew. We knew that we, our world, we the living, were to know agony more sharp, heartbreak more cruel, desolation more awful than any before us.”

Campus was transformed in the following months. While the importance of education was still emphasized by administration, it realistically took the back burner. If students could do anything to help the wartime efforts, even if that was through putting on theatrical performances for soldiers, that was prioritized. Those training for war struggled to keep up with shortened class schedules. New courses were introduced covering war-related topics. Barracks took over buildings. Activities unrelated to the war were scarce.

February 1942 — the date written in elegant cursive beside Monroe’s name on the inside of the philosophy textbook.

Tom Westerlin wrote in the Daily Illini about the hard turn from planning his career to preparing for war, “We’ve read about these things; some of us have written about them. But we don’t really know these things yet.” Monroe may have read about war in that sage-green textbook, which tied in events from World War I to Plato’s philosophy. I wonder how his perspective changed in the years that followed.

By April, Monroe was training for war. The Daily Illini reported, “Lawrence Monroe ex-’44 recently enlisted for flight training in the navy air force. After primary training at Glenview, he will report to one of the navy advanced flying schools for secondary instruction.”

Nearly a year after that, the Daily Illini reported Monroe’s transfer to a naval air training center in Corpus Christi, Texas, having completed his primary training.

That is the last mention of Monroe until after the war. He continued to participate in gymnastics, became a member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers program committee, and graduated with his degree in mechanical engineering in 1948.

The story behind the leaf

With all the snippets of information from yearbooks, news articles, and historical records, we have a timeline.

Monroe of Chicago enrolls at U of I in 1940 as an engineering student. As a sophomore, he pledges to Delta Sigma Phi and makes varsity gymnastics. Pearl Harbor is attacked, the U.S. enters World War II, and Monroe watches a very talented fellow gymnast on his team get drafted. In the spring, he starts a philosophy class, but by April, he’s enlisted in flight training for the navy air force. The textbook he acquired for philosophy is set aside.

World War II ends in 1945, and Monroe returns to classes by fall of 1946. Perhaps he revisits that philosophy course he rushed through in the chaos of training or never got to finish. On a nice October day, he sits down on the Quad to read from his textbook, but the content hits differently after everything.

Alternatively, that philosophy book could have been collecting dust on a shelf, and when Mornoe needed a book to preserve a leaf in, he chose the one for a class he’d long left behind.

Either way, a perfect brown oak leaf catches his eye. It flutters down gently. Peacefully. It is beautiful. Untattered. Whole.

Perhaps it is a new appreciation for life that prompts Monroe to pick up the leaf. Perhaps it symbolizes a time of peace as he looks around campus at all that was lost. Perhaps he records the date and location as a way of saying “I am here” — a grounding moment after fearing he may never return to this campus, this quad. Perhaps I am overanalyzing a man’s interest in a really nice leaf.

He keeps the sage-green philosophy textbook throughout his long, successful life. In 2007, he passes away in Erie, Pa. The book ends up in a vintage shop, and almost two decades later — eight decades since the leaf was put in — a collector rediscovers it.

—

We’ve done a lot of research and quite a bit of speculating. I do not wish to assign any of my own thoughts to Monroe or the other students who lived through this time. No matter how many archives I look through, I can never truly know what was going through their minds. But to try to put yourself in the shoes of someone who lived before you, to imagine what thoughts were going through their mind, to empathize and be mindful… I believe that is how we learn from the past. So, I implore you to take one more walk with me.

It’s Thursday, Oct. 24, 1946. The war is over, and the campus is busy again, but there will always be holes from those who didn’t make it back. Holes that can never be filled. Classes never finished, diplomas never received. Dreams killed. Classmates, friends, and partners ripped away, robbed of this beautiful autumn day.

You sit down outside Lincoln Hall, staring out onto the Main Quad. The leaves are a stunning array of reds, oranges, and yellows. Squirrels hop around, gathering acorns for the winter, just like every other year. Then, a brown oak leaf falls into your lap.

What do you do?