Poet Ángel García examines his disrupted family lineage in his new collection of poetry, seeking answers about where he came from and trying to fill the many gaps in his family’s story.

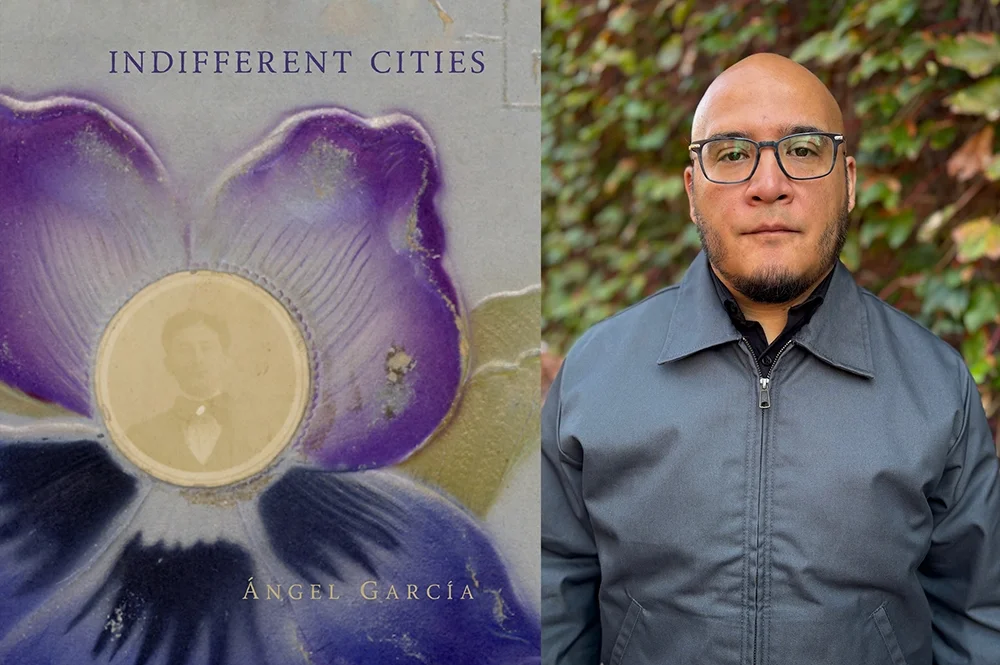

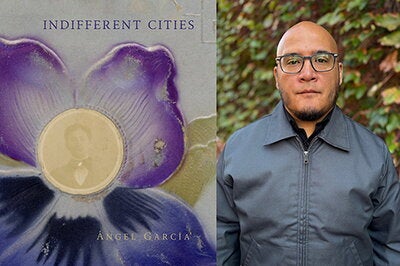

“Indifferent Cities” is the second book by García, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign English professor. The book was the winner of the Helena Whitehill Award, given to a work of poetry or creative nonfiction by Tupelo Press, which also publishes the winning manuscript.

García described his work as “documentary poetics,” a way of looking at time and histories in a different way, recognizing that they can be as important and exist in the same sphere as the present. His poems depict his exploration of the lives of his ancestors in Mexico, his parents’ migration to the U.S. and their frequent travels back and forth across the border. He described his parents as “notorious nonstorytellers.”

“They didn’t talk about their childhoods, their past, why they came to this country or why they were interested in going back so often,” García said. “Because there are so many gaps and so many silences that exist in my family, I was longing to know more.” His poems are “contending with that longing and figuring out what I know, what I don’t know and trying to reconcile those things,” he said.

“I ask my father what is your mom’s name? the wrinkles on his forehead clustered, his jaw pulsing tight signal to me I’ve done something wrong.”

– “Sin Nombre”

García searched for birth and death certificates of family members, but many public records were handwritten and have faded or become illegible, or they contain misspellings of names and inaccurate dates of birth. In several of his poems, García uses brackets around blank space, indicating where family names not known to him should be written.

He read letters, postcards and his grandmother’s life story that she wrote in a spiral notebook, and he became intrigued with a 1911 postcard written by his great-grandfather, a poet. García’s mother claimed to have found his grave with a poem engraved on the tombstone, but García has been unable to find either the grave or any existing poetry.

“Ancestry is a language I’ve not learned to speak.”

– “Those Graves”

García’s poems trace his grandparents’ journeys through various locations in Mexico, and his family’s frequent moves between California and Texas. “Places I’ve Learned to Forget” lists the many schools he attended. “Burials” describes how he and his brother buried some of their belongings in a box in a backyard before another move.

“It’s not just the arrival, but the return and the challenges of being able to go back, particularly for folks who are undocumented. It compounds the challenge of remembering who you are and where you come from,” García said.

“In the country we’ve both longed for, and my mother has made into memory, she tells me this is where you belong. … Inside the 200-passenger flight of her memory where I am only a guest, I think Then why did it take you so long to bring me here?”

– “Layover/Overlay”

The book’s title, “Indifferent Cities,” comes from a line in the poem “To the Hotel Saint Antoine” by Nobel Prize-winning poet Derek Walcott. For García, it evokes the nostalgia for places and events from childhood, and the realization that “the city itself has no memory. It changes, adapts, grows. There’s this way that it moves beyond the value and nostalgia and memory we have of that place. This living, thriving, breathing thing that has little regard for us as people who are from there or who have lived there,” he said.

While writing the poems, García said he began to notice similarities and patterns between his own experiences of loss and that of family members.

“The silence and trauma aren’t within its own generation. They come from further back,” he said.

García said his work proposes that there can still be a narrative and an understanding of one’s lineage without knowing or understanding all of its details.

“We try to create a mosaic of what exists. We have to imagine what some of those possibilities are without facts and data,” García said.

As difficult as the poems were for him to write, the experience helped him get closer to the people and places he comes from, García said. The best thing that has happened from writing the book, he said, is that his brother and nephews read it and came to him with questions about their family.

“Silence was something I did not want to inherit, or pass down to my son, should I one day have one, because I don’t want you to live with a fervent ache of knowing so little about the man you love. … I want you to hear the stories from me, while we sit across the shadows of a fire we’ve made, smoke lingering on both our bodies, contented to sleep beside each other long after the fire has burned off and the morning has grown cold because you know not only how to tend a fire, but how to stoke it with story.”

– “Kindling”

In one of the final poems of the collection, García describes walking with his young son in Guadalajara, Mexico, where his grandmother was married and his mother was born. His mother is uncertain where in the city she was born, and García struggles to identify meaningful landmarks for his son.

“Soon, we will depart this place and never return: the first of many cities he will leave, just as the past has left us with the litanies of indifferent cities we will faintly remember as ours.”

– “Guadalajara”