Over a span of eight years, from 1935 to 1943, a cadre of 13 government-sponsored photographers captured the fabric of rural America by exposing the profound poverty experienced by migrant workers and tenant farmers, who were some of the nation's most invisible citizens during the Great Depression.

The Historical Section documentary project was underwritten by the Farm Security Administration, a New Deal Agency created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The photographers involved, including Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, achieved world fame, as did some of the photos themselves. The project's goal was to document rural America in order to shape public discourse concerning the struggling American agricultural economy.

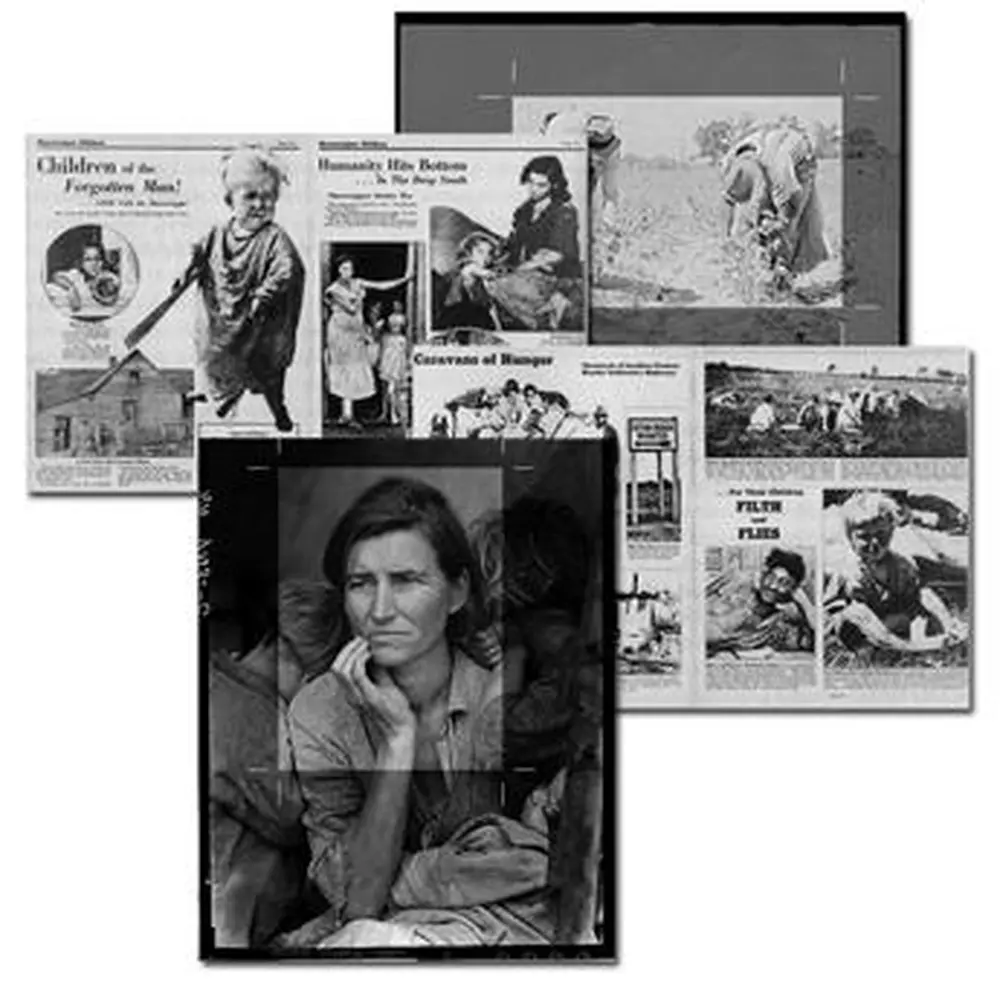

Over the years, the indelible images-which number in excess of 250,000-have been the subject of extensive scholarship. Cara Finnegan, an assistant professor of speech communications in LAS, looked at the project in a different light in her book Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs. Rather than examine the photos as individual images, she studied the photos in the context in which they were presented to the American public-in the pages of various contemporary periodicals.

"The people who ran the project wanted the poor to be viewed sympathetically and also heroically-that these are the real great Americans," says Finnegan, who continues to examine how images are used to persuade politics.

Finnegan's research revealed that the messages the photos conveyed weren't universal, but rather depended on the magazine's agenda. Finnegan compares the presentation of the photos in three very different publications-Look, a mass-produced consumer picture magazine; Survey Graphic, a periodical devoted to advocating progressive issues; and U.S. Camera, a glossy annual that compiled the best of American photography. What she found is that there was no one way that the American public pictured poverty during the era.

Look, Finnegan discovered, gave readers a voyeuristic view of rural poverty, illustrating it rather than offering any understanding of it. U.S. Camera offered the photos without commentary, instead dissecting a photo's technical and aesthetic qualities. Survey Graphic depended on the photos to "illustrate the journal's major themes," Finnegan says, making them fit whatever agenda the editors wanted to promote. The photos accompanied various articles about the New Deal and Depression in general, not just those focusing on the era's farming issues.

The treatment of the famous "Migrant Mother" by Dorothea Lange, which Finnegan describes as "a condensation symbol for all Depression-era suffering and poverty," enforces her point. A weathered woman sits with a young child on both shoulders and a baby in one arm. U.S. Camera displayed the photo without a caption. In Survey Graphic, the photo became a symbol for the article it accompanied, which was a story about migrant workers who had no work because of a crop failure.

Despite their various circulation rates, the photos have had a lasting power. Finnegan regards the project's success in establishing a visual record of the era in American history as its most important legacy.

"It's unprecedented," says Finnegan, whose book won the National Communication Association's 2004 Diamond Anniversary Book Award. "For the government to pay people to take pictures of America and Americans was pretty unusual. That record remains and it's there for everyone to study and look at whenever we want. It's an incomplete record but it tells us a lot about life in that time period."

See the collection in the Library of Congress.