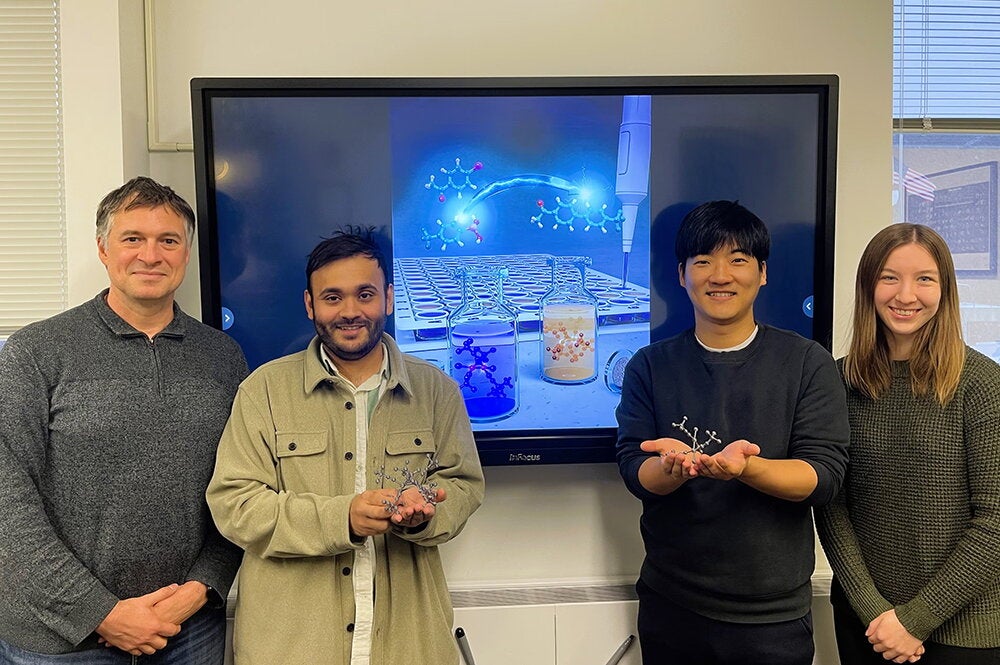

Using a technique employed by astronomers to determine stellar surface temperatures, chemists in LAS have measured the temperature inside a single, acoustically driven collapsing bubble.

Their results seem out of this world.

"When bubbles in a liquid get compressed, the insides get hot-very hot," says Ken Suslick, the Marvin T. Schmidt Professor of Chemistry at Illinois and a researcher at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. "Nobody has been able to measure the temperature inside a single collapsing bubble before. The temperature we measured-about 20,000 degrees Kelvin-is four times hotter than the surface of our Sun."

This result has raised eyebrows. Sonoluminescence arises from acoustic cavitation-the formation, growth, and implosion of small gas bubbles in a liquid blasted with sound waves above 18,000 cycles per second. The collapse of these bubbles generates intense local heating. By looking at the spectra of light emitted from these hot spots, scientists can determine the temperature in the same manner that astronomers measure the temperatures of stars.

By substituting concentrated sulfuric acid for the water used in previous measurements, Suslick and graduate student David Flannigan boosted the brilliance of the spectra nearly 3,000 times. The bubble can be seen glowing even in a brightly lit room. This allowed the researchers to measure the otherwise faint emission from a single bubble.

"It is not surprising that the temperature within a single bubble exceeds that found within a bubble trapped in a cloud," Suslick says. "In a cloud, the bubbles interact, so the collapse isn't as efficient as in an isolated bubble."

What is surprising, however, is the extremely high temperature the scientists measured. "At 20,000 degrees Kelvin, this emission originates from the plasma formed by collisions of atoms and molecules with high-energy particles," Suslick says. "And, just as you can't see inside a star, we're only seeing emission from the surface of the optically opaque plasma." Plasmas are the ionized gases formed only at truly high energies.

The core of the collapsing bubble must be even hotter than the surface. In fact, the extreme conditions present during single-bubble compression have been predicted by others to produce neutrons from inertial confinement fusion.

"We used to talk about the bubble forming a hot spot in an otherwise cold liquid," Suslick says. "What we know now is that inside the bubble there is an even hotter spot, and outside of that core we are seeing emission from a plasma."

Their work is funded by The National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.