By Vernon Burton

Dr. Burton is a professor emeritus of history, sociology, and African American studies at U of I and is the author of Age of Lincoln.

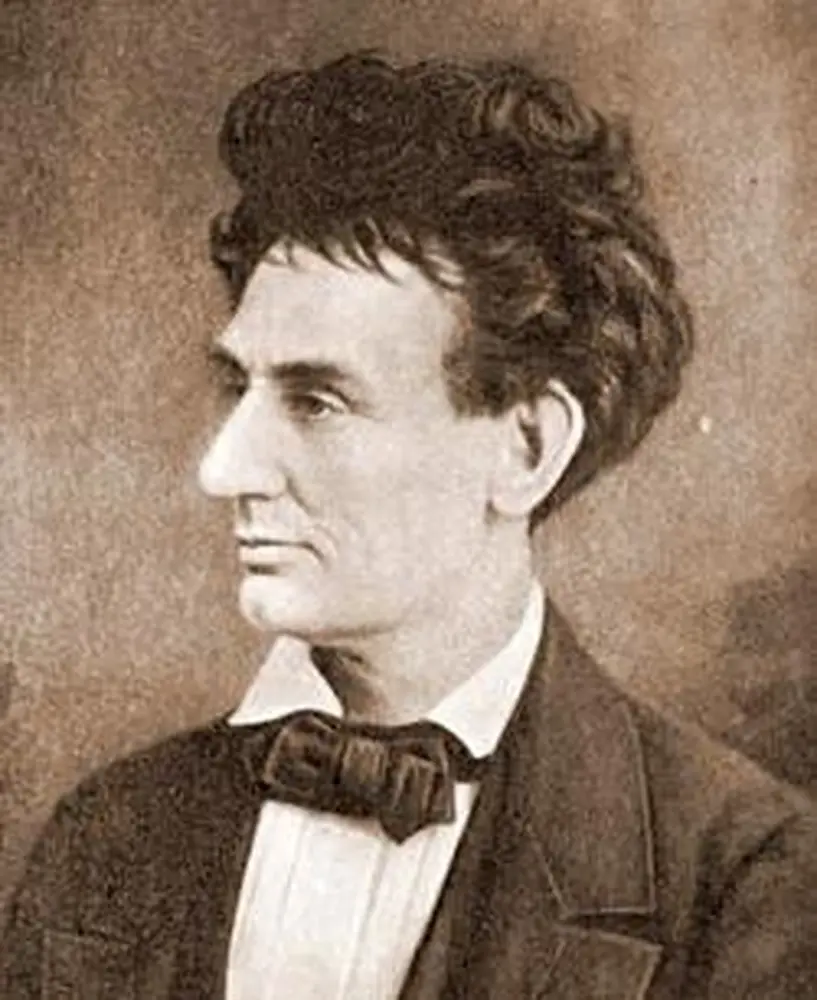

In September 1837, Abraham Lincoln received his license to practice law, and on April 15, 1837, he relocated to Springfield, Illinois’ new state capital, to join the law office of fellow Whig legislator John Todd Stuart. Nine months later, on January 27, 1838, he addressed the citizens of Springfield. Gathered at the Baptist church to attend a public meeting of the Young Men’s Lyceum, these men and women of Springfield came to hear this now-veteran member of the Illinois House of Representatives who was still a relatively new resident of Springfield.

Disturbed by recent mob violence in Mississippi and St. Louis as well as the killing of abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy, Lincoln delivered a speech on “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” Displaying a loquaciousness he would prune in subsequent years, the young congressman staked the nation’s future on “a reverence for the Constitution and law” (Lincoln’s italics), for which he recommended that “every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor.”

The “mobocratic spirit” of the times rendered extrajudicial judgment against gamblers, abolitionists, suspected slave insurrectionists, and an accused Mulatto murderer; nationwide, he worried, “wild and furious passions” refused to concede to an orderly judicial system. Evoking the specter of dead men hanging from every tree along the road, Lincoln called on Americans to renew their patriotic attachment to sober reason, law and order, and the political edifice of liberty and equal rights bequeathed to them by their forbearers.

All too aware of human frailties, Lincoln readily granted the existence of bad laws, of righteous grievances, but the “political religion” he espoused was necessarily a never-ending exercise, a halting process towards greater justice—not perfection. Bad laws were to be repealed and new legal provisions applied to new grievances. “Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason” was the foundation for America’s future support and defense.

Here was boundless commitment to, if not necessarily blind faith in, general intelligence, sound morality, and reverence for the rule of law. And on its strengths, the 28-year-old Lincoln was prepared to assert that even “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” Throughout his life, his belief in the rule of law as outlined in the Lyceum speech, and his belief that only by adherence to the laws and processes of government could the United States persist, would be the bedrock of Lincoln’s philosophy.

Read the other monthly essays in this special commemorative series.

- October 13

- Lincoln’s Rhetorical Worlds, Professor Michael Leff

- November 11

- Lincoln Lecture, Professor Robin Blackburn