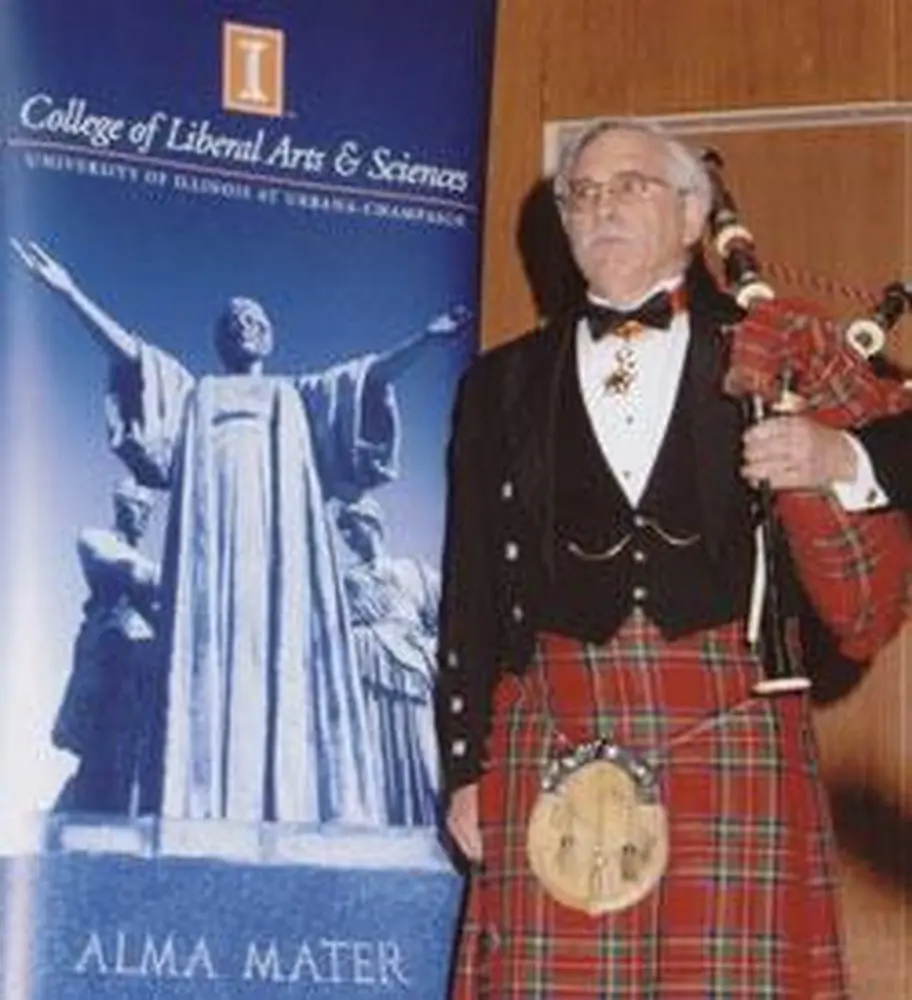

After 25 years of leading LAS graduation convocation processions, John Lynn is accustomed to playing bagpipes in the spotlight. He rather likes it; he can’t count how many graduates have taken their picture with him, and with at least a dozen songs committed to memory (and upwards of 60 when he plays more often) it’s safe to say he loves the music.

Lynn is quick to claim he’s merely a “competent” player, but you might say he has high standards considering that he plays the complicated and potentially hair-raising instrument so well that graduation organizers consider him a tradition. Even if he’s not the best bagpiper this side of Scotland, he is among a rare breed.

This spring’s ceremonies will be his swan song, however, both as graduation bagpiper and professor in the U of I’s Department of History. Lynn, 66, will retire after 31 years of teaching military and French history at his alma mater. For those whose only memory of him is of solitary bagpiper marching in before the crowd, it’s an appropriate one. Those who know him describe him as one of a kind, too.

A Peace-Loving Military Historian

He first arrived on the U of I campus in 1962 as a student who hit the books on military history like his famous classmate Dick Butkus hit ball carriers. Lynn blazed through undergraduate studies in 2½ years, though he found time to become the campus’s first white member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the oldest black fraternity. He also served as vice president of the local NAACP and in the spring of 1964 trucked supplies to striking sharecroppers in Mississippi.

When he returned to campus in 1978 it was as a professor to assume a line of teaching military history on campus that stretched back to the 1940s. By then, however, Lynn had learned that not everyone loved military history. His voice stiffens as he recalls condescension he received years ago from fellow graduate students in California who looked down upon military history, which flew contrary to a shift in the 1960s toward the study of social topics such as class, race, and women.

“Things are changing now, but for a long time, and I mean really until the last couple of years, military history has been regarded as a kind of pariah field. For example, it isn’t women’s history, it’s almost men’s history. So it doesn’t fit in. It’s not a socially uplifting history,” Lynn says. “To the people who are attracted to their fields for their social implications, military history is a suspect thing after all.”

For the record, and to address old questions that dog military historians, no, he didn’t serve in the military—in fact, he doesn’t think it’s necessary for someone who wants to study the history of war—and he doesn’t like war. Indeed, part of his post-retirement will be spent in an unpaid position working with the University’s Program in Arms Control, Disarmament and International Security.

Fighting for an Unpopular Profession

Yet over the years, Lynn, who has also served as president of the United States Commission on Military History, among other similar positions, has fought hard for his field and evolved into a prominent voice for military historians. In 1997 he wrote an essay called “The Embattled Future of Military History,” and was quoted extensively by U.S. News & World Report in a story regarding the plight of academic military historians.

Of some 150 colleges and universities that offer PhDs in history, according to the magazine, only a dozen offer a military history program. Lynn recently surveyed 30 years of back issues of American Historical Review and found not a single article on the conduct of the Revolutionary War, World War II, or Vietnam.

It’s an egregious oversight, Lynn believes, because he sees military history as vitally important. “People are fighting and dying, there are life and death issues, there are issues about the state, there are issues about class and power on the highest levels,” Lynn says.

He has found, however, that there’s ample room for social history in his field. His most recent books include the popular, award-winning Battle: A History of Combat and Culture, and most recently, Women, Armies, and Warfare in Early Modern Europe, the first and so far only book-length discussion of women in early modern armies.

That kind of adaptability has earned him respect and continued attention. His colleague and former student, Michael Hughes, an assistant professor of modern European history at Iona College, earned his PhD under Lynn and calls his old teacher one of the most innovative scholars in his field.

But his proudest memory of Lynn came after the attacks of 9/11, when Lynn was interviewed on a local TV station.

“One of the things he was very careful to say was that we need to remember who we are as a country, and we need to make sure we don’t lash out and hurt innocent people,” Hughes says. “I really respected and admired him for that. I thought what he was doing was very important.”

Larger than Life

Hughes also describes Lynn as “larger than life” with a deep passion for his field. You may surmise this from Lynn’s sons, Daniel Morgan Lynn and Nathanael Greene Lynn, whom Lynn named after Revolutionary War generals, or his many honors, including the French Palmes Academique and the Moroccan Ouissam Al Alaoui. But he’s also a recognized teacher, with many awards to his credit and a decade of leading study abroad trips to France. Lynn also notes the unusual fact that every graduate student who earned a doctorate with him as their main advisor are employed somewhere as historians.

He produces writing and research at a frenetic rate by scholarly standards, having authored seven books on military and French history, edited three other books, and written more than 80 chapters and papers.

“To me the writing of history is like the building of a house,” says Lynn, who comes from a long line of contractors and recently remodeled his own home. “It’s a construction project. It isn’t about perfection. It isn’t about never making a mistake. It’s about making a usable product. That’s the wrong word in a sense but it’s building something.”

Next year someone new will do the bagpipes at LAS graduation convocation—organizers say it is now a tradition even though Lynn will not be doing it—and the Department of History says it hopes to eventually replace Lynn with another military historian.

Lynn will be teaching part-time in a vibrant military history program at Northwestern University, not far from where he grew up. He loves the field too much to leave it, and he abhors the idea of a restful retirement.

In fact, you get the notion that he abhors rest, period. True, he has a stuffed chair in the corner of his soon-to-be vacated office in Gregory Hall, accompanied by a weathered foot stool, but as he sits there he rocks furiously, eyes upward, and as he mulls over his work, the chair creaks and creaks and ideas erupt in his head like the notes to Scotland the Brave. He’s thinking about surrendering.

Not as a career move, mind you. Surrender is his next research topic.