It’s unpredictable. It has sexual issues. It has a complicated past. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that the tropical fruit papaya could offer scientists insights into how humans evolved.

Research originating at the University of Illinois has revealed that papaya sex chromosomes have undergone dramatic changes in their relatively short evolutionary histories. The changes that scientists observe in the plant now hint at changes that may have occurred in human sex chromosomes, but have become lost with time.

The studies show that the papaya sex chromosomes—which are about 7 million years old, in contrast to human sex chromosomes, which began their evolution 167 million years ago—are increasing in size and reorganizing themselves. Some genes are being lost while others are still present as pseudogenes, which are no longer functional but give researchers an opportunity to see evolution in action.

Gene loss in the Y chromosome is well documented in ancient Y chromosomes, but gene loss in the X chromosome, particularly at this early stage, is unexpected, as is the expansion of the X chromosome, says plant biology professor Ray Ming, who led the studies.

“This is the first look at an early stage of sex chromosome evolution,” says Andrea Gschwend, who conducted the research with Ming while she was a doctoral student in his lab. “Usually people will focus on the ancient sex chromosomes because they are the most relevant to us,” she says. “So this is the first direct and complete look at a more recently evolved sex chromosome system.”

Analyzing the X chromosome is vital to understanding the evolution of sex, says Ming. The new findings in papaya suggest that the human X chromosome, too, has undergone numerous changes since it first distinguished itself from the autosomes, Ming says. Such changes are not detectable because the ancestral autosomes are no longer available for comparison, he says.

Because the papaya sex chromosomes are young and can be compared to closely related autosomes in a sister species, they offer a view of the early events of both X and Y chromosome evolution, Ming says.

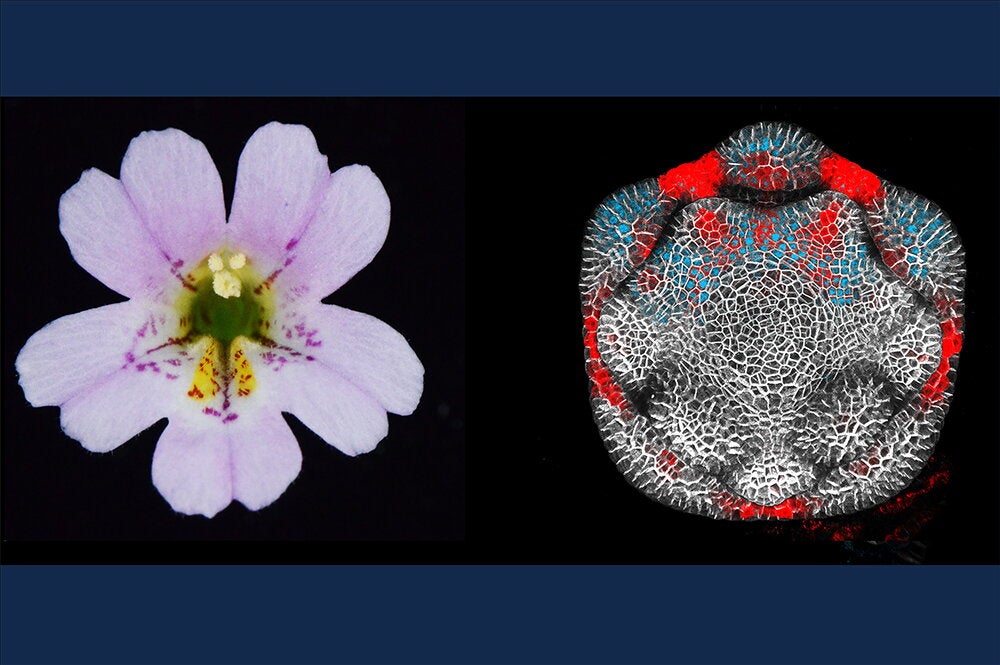

Studying papaya sex chromosomes is a complicated task. The papaya has male, female, and hermaphrodite sexual types, with two kinds of Y chromosomes. Papaya plants may produce combinations of male and female or hermaphrodite and female plants.

This complexity causes problems for papaya growers, Ming says. Hermaphrodites are the most productive of the papaya sexual types and yield the best fruit, but the offspring of hermaphrodites are not all hermaphrodites. To aid growers, Ming and his colleagues aim to develop a “true-breeding” hermaphrodite papaya variety that consistently produces hermaphrodite offspring.

All of the findings are significant and useful, Ming says, but the X chromosome, which is generally overlooked in models of sex chromosome evolution, offered the most surprises.

“These studies are changing our view of sex chromosome evolution, particularly X chromosome evolution,” he says. “We now know that both the X and Y chromosomes are dynamic in the early stages of their evolution, not only the Y chromosome, as previously thought.”