“What think you of books?” Mr. Darcy asks Elizabeth Bennet in Jane Austen’s immortal novel, “Pride and Prejudice.”

“Books—Oh! no.—I am sure we never read the same, or not with the same feelings,” answers Elizabeth.

Today, more than 200 years since “Pride and Prejudice” was published, the digital revolution has transformed books in ways that would astound Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy, not to mention Jane Austen. But one thing has not changed. The proportion of women characters and women writers is roughly the same today as in the days when Austen’s characters were exchanging witty barbs in drawing rooms.

In fact, Ted Underwood, a U of I English professor, found that through most of the 20th century there were actually fewer women writers and female characters in proportion to men compared to Austen’s time period. It wasn’t until the last 30 years that the ratio of male to female writers has returned to the level of the early 1800s.

Underwood’s work reflects a dramatic change in the way research is being conducted in the humanities. His research is part of the emerging digital humanities—a field that puts computers to use in creative ways not possible even 20 years ago. He’s one of several LAS faculty whose humanities research has been enhanced by computing power.

“I tried to do this kind of work in the 1990s, but the resources just weren’t there,” said Underwood. Today he has teamed up with Sabrina Lee, a graduate student in English, and David Bamman, an information scientist with the University of California at Berkeley who has developed an algorithm that can analyze words and even character descriptions in hundreds of thousands of digitized books.

So why did the proportion of female writers go down in the 20th century? Ironically, Underwood believes that women’s expanded roles throughout society may have been the reason.

“During Austen’s day, fiction writing was one of the acceptable pursuits for women,” he said. “But as there were more opportunities for women, many of them moved out of fiction.” This decline was halted beginning about the 1970s.

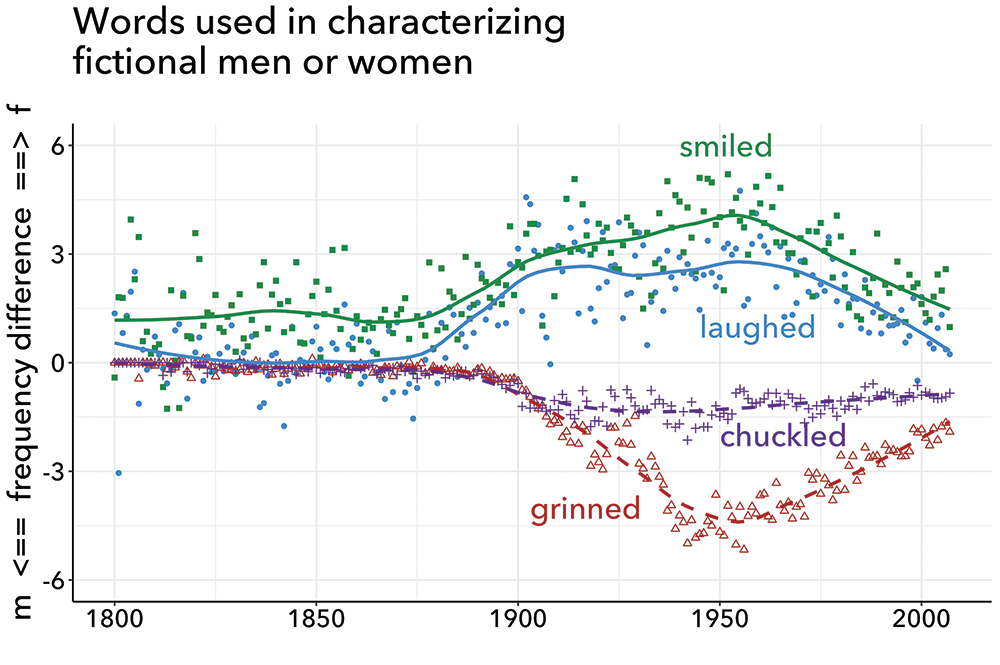

Digital tools have also allowed Underwood to study changes in genres, as well as gender stereotypes in literature.

“In the 19th century, if the inside of a character’s mind was described at all, she was likely to be a woman,” he said. “The inward world was described for feminine characters, while the men were out there waving their swords.”

What’s more, if a character’s eyes or hair were described, she was most likely a female character. But if the person’s chest or jaw was described, the character was probably a man.

To do this research, Underwood has tapped into HathiTrust, a massive digital library founded at Illinois. Meanwhile, Mara Wade, U of I professor of Germanic languages and literatures, works with Tim Cole and Myung-Ja Han at the U of I Library to lead Emblematica Online, a major effort to digitize and make accessible rare Renaissance emblem books.

“The new technology leads to the creation of new knowledge because digital resources have made it possible to ask different questions,” she said.

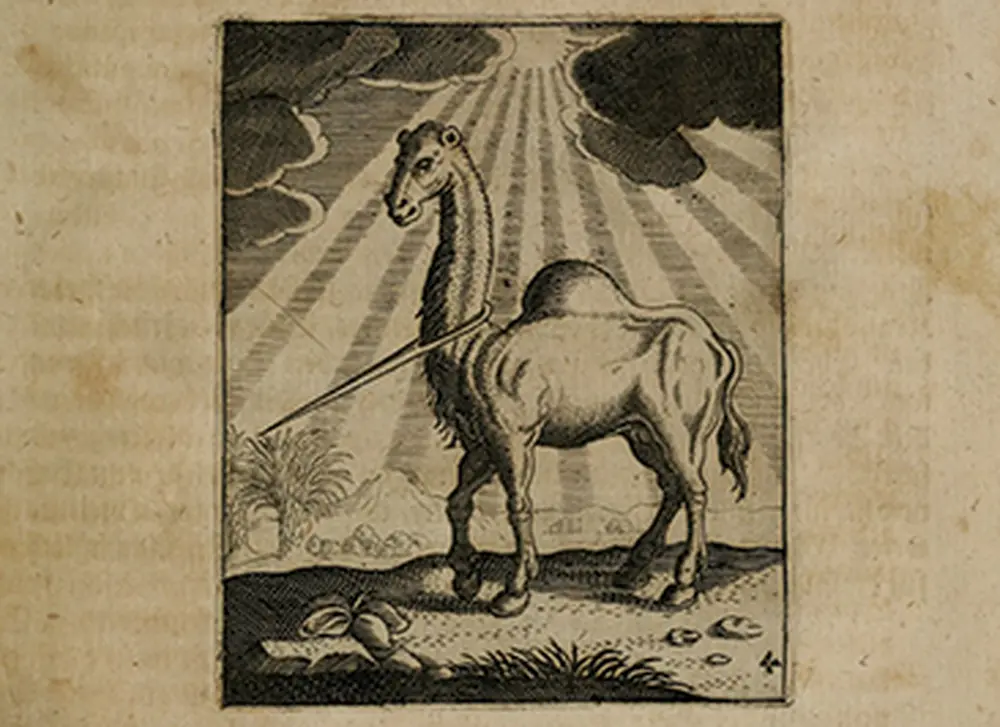

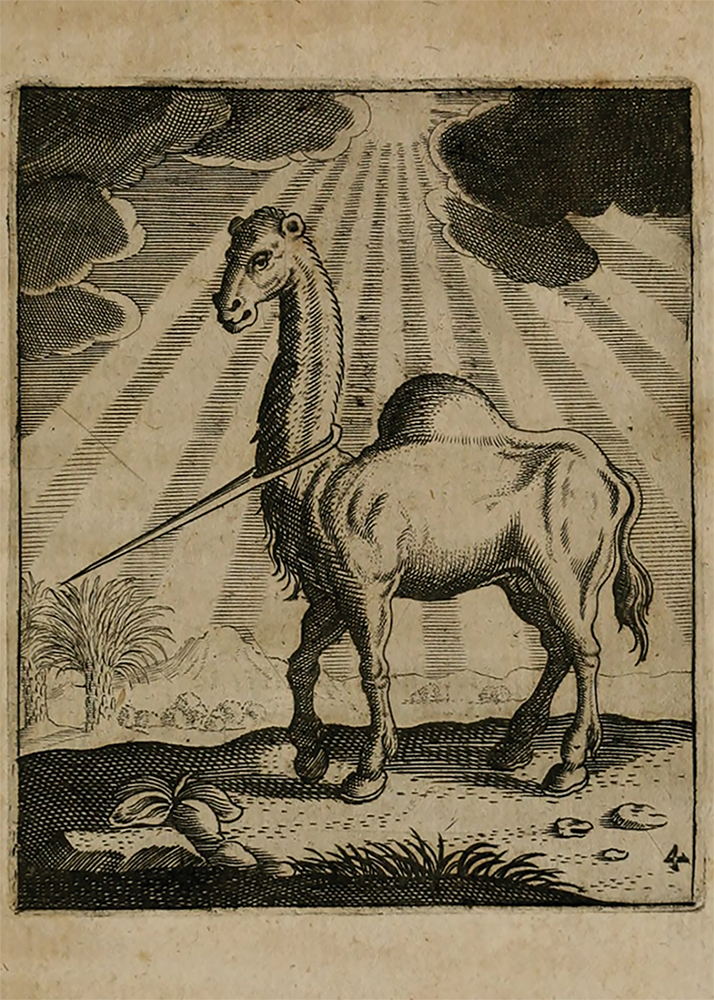

Emblem books were the rage from 1521 to 1750, and Wade said they “open a window into the mentalities and attitudes of people in the Renaissance world.”

An emblem is a symbolic image accompanied by a brief text and an epigram, or short poem. A single book can contain up to 1,500 of these emblems. As one example, Wade cites an emblem that depicts the goddess Fortuna standing on a rolling globe (shown below). She holds a sail in her right hand and a waxing moon in her left, and the epigram says, “Fortuna ut Luna” or “Fortune is as the moon.”

It’s another way of saying that our fortunes wax and wane like the moon.

The U of I holds one of the largest collections of emblem books in the world, and about 53 percent have been scanned and digitized, as well as indexed with data that makes them searchable and widely available for research and teaching. In addition, Emblematica Online provides access to emblem collections at universities in Glasgow, the Netherlands, and the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Germany, as well as Duke University Library and the Getty Research Library. In all, roughly 1,400 of these rare books and 30,000 emblems have been digitized and indexed.

“For literary scholars of the Renaissance and art historians, those 30,000 emblems are gold,” Wade said.

The secret to using this collection is Iconclass—a classification system that describes art, allowing researchers to search for images by specific themes or content. Iconclass tags each image with alphanumeric notations that describe what is depicted in the emblem. For instance, the code 25F24 is a camel. If any emblem includes the image of a camel, it is tagged with 25F24, among other notations. This universal language enables researchers to scour the extensive database for specific images, and they can search in English, French, German, and Italian—the key languages of the Renaissance.

The research possibilities are endless. For example, a grad student from Arizona was researching medicine in 16th- and 17th-century Germany. Using Emblematica Online, the grad student found a storehouse of emblems depicting medical scenes, such as amputations or a family weeping over a deceased infant.

“There was an emblem for almost everything in the Renaissance,” Wade said.

In the past, researchers had to travel the world to study these rare books, but digital facsimiles make it possible to study them without leaving their desk. Emblematica Online also enables researchers to study large numbers of emblem books, not just

a handful at a time.

Emblematica Online puts the digitized books in a researcher-friendly format, but that is not always the case with historical materials you find on the internet, said John Randolph, U of I history professor. You can find all kinds of YouTube videos depicting events from history, but researchers’ questions about online historical sources abound. Where did the video come from? Is it under copyright? Is it the entire film or only part? Has the video been doctored?

“The majority of digital records being created online do not provide this basic information,” Randolph said. While the internet brings historical artifacts to a wider audience, he added, “that doesn’t necessarily make them intellectually more accessible, or make them more useful in understanding history.”

Traditionally, universities, colleges, archives, libraries, and publishers ensured that historical material came with critical supporting information. To merge the traditional methods of publishing history with the online world, Randolph and several other Illinois professors are leading a team in tandem with the University of Nebraska and Michigan State University, using a grant from Humanities Without Walls.

The grant supports SourceLab, which Randolph runs to train students on how to put online sources in a form that historians can use. For instance, his students worked on a 1918 silent movie showing French sculptors preparing masks for soldiers who suffered terrible facial wounds during World War I. SourceLab provides a thorough description of the source, copyright, and other details about the movie, such as where and how it was preserved. It also places the film in a context, explaining that this short movie was just one of many—although most were discarded or burned.

Digital humanities, with its emphasis on both quantitative and qualitative research, has opened the door to more interdisciplinary studies, such as Underwood’s work with the Berkeley information scientist.

In addition to SourceLab, the Humanities Without Walls grant supports the Public History initiative coordinated by Kathryn Oberdeck, history professor, and Daniel Gilbert, professor of labor relations and history. Public History aims to connect students with community history projects that will produce digitized documents and exhibits. The initiative also involves public history interns who put together “hidden history” tours about places associated with underrepresented student activism on campus.

You can also find interdisciplinary work in the research of Robert Markley, professor of English and an 18th century specialist. Together with researchers from two other universities and an Illinois computer scientist, he developed software to analyze 237 maps of the Great Lakes. The maps, published between 1680 and 1730, are works of art, but they were also created for commercial and political reasons. Markley studied them for environmental and climatological information.

In another digital humanities effort, Randall Sadler, professor of linguistics, recently coordinated an international conference dedicated to the use of computer technology to learn languages. The Computer-Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO) drew several hundred people to the U of I campus this past summer; it brought into sharper focus all kinds of ways to teach language with new technology, including virtual reality, podcasts, and word games on smartphones.

“My hope for the digital humanities is that we’re starting up new conversations with many types of scientists,” Underwood said. “You don’t have to put on different-colored spectacles to look at literature and then put them away when you look at law or social history. It’s all part of a single story.”

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2018 LAS News magazine.