In 1995, Eduardo Ledesma graduated with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and became a bridge engineer. For 10 years, he got up every morning, went to work and did what he had trained to do. And then, something changed.

“I had always been fascinated by the humanities,” said Ledesma. So, just for fun, he started taking night courses in Spanish and Latin American literature at the University of Illinois at Chicago. That led to a master’s degree, which led to a doctorate in romance languages and literatures at Harvard, which ultimately led him back to Illinois, where he’s currently an associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese. Today, he’s still building bridges, only now they’re metaphorical as he makes new connections at the intersection of engineering, technology, and culture.

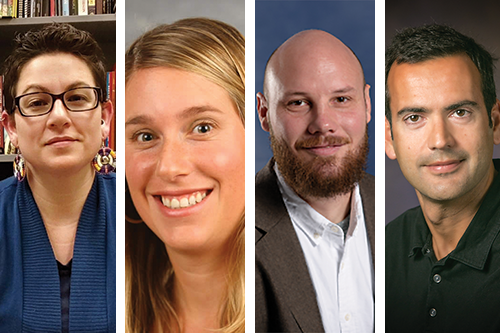

There are almost 320 assistant and associate professors in LAS like him who are making similar connections. For this issue, we spoke with four of them—Ledesma; Alison Fout in chemistry; Jenny Davis in anthropology, American Indian studies, and gender and women’s studies; and Daniel Hyde in psychology. Together, they provide just a small sampling of the amazing up-and-coming faculty members who are building bridges, from the known to somewhere beyond. For many, it’s too soon to know where their research may lead. The scaffolding they’re building could broaden what we already know, solve important global problems, or simply lay the groundwork for others who will one day venture beyond our current horizon. Like all the explorers who’ve come before them, however, they believe that the potential rewards make the journey worthwhile.

Since joining the university in 2012, Ledesma has emerged as one of the leading researchers in 20th- and 21st-century Latin American culture and literary studies. He’s currently completing his second book, “Cinemas of Marginality: Experimental, Avant-Garde and Documentary Film in Ibero-America,” and working on a third, which will explore how those who are visually impaired interact with the visual arts.

He’s part of a field of study known as digital humanities, which uses digital tools to enhance the study of humanities and traditional humanistic disciplines to understand the digital world. With a background in engineering and computer science, it was the perfect fit.

“I find the intersection between the humanities and the digital as the ideal space to study our 21st century cyber culture,” Ledesma said. Whether it’s researching digital poetry from Uruguay, or “live coding,” which uses improvised computer code to create music and visual effects, he loves exploring the various ways that humans both adapt—and adapt to—technology.

In his new book, “Blind Cinema: Visually Impaired Filmmakers and Technologies of Sight,” there’s an entire chapter devoted to a genre of videos made by visually impaired vloggers narrating their life experiences. Because they may only experience texts as sounds and images as audio descriptions, visually impaired YouTubers use special software to produce and upload videos, create vlogs, and establish a sense of community. Through contextual and visual analysis, he hopes to enhance the interpretations of cultural trends in this unique community.

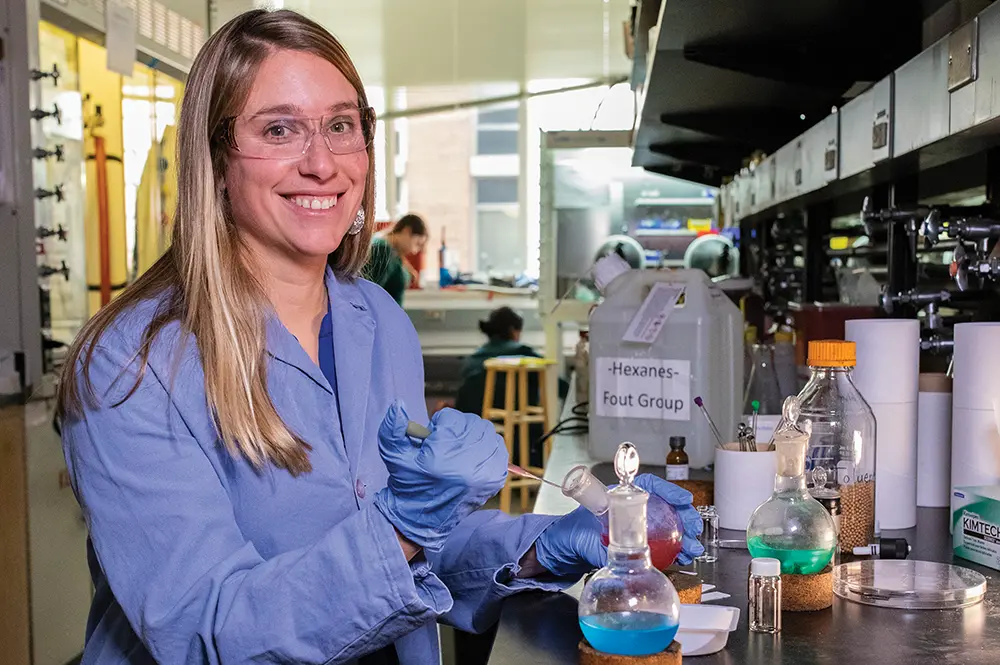

While Ledesma studies the power of images to transform lives, Alison Fout is exploring the power of images to save them. As an associate professor in chemistry, she’s researching new catalysts that could one day solve a growing list of environmental, biological, and energy problems. Currently, she’s part of a team working on a replacement for gadolinium, a common contrast agent used in magnetic resonance imaging that’s been in the news since a 2014 study indicated it could be retained in the brain, leading to possible health problems.

In addition to being safer and more sustainable, the new catalyst could aid in providing contrast agents that generate higher resolution images and one day enable physicians to track the movement of cancer cells. “If you have a cancer cell and you inject this, the cancer cell will target the agent and then you can track it through the body,” Fout said. “That’s the dream.”

That’s why grants are important. And Fout has earned several, including the prestigious Marion Milligan Mason Award for women in the chemical sciences from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which came with a $50,000 grant. With these funds, along with grants from the National Science Foundation, the College of LAS, and others, she can continue to work on the new contrast agent, while exploring other important research pursuits.

One of those could be of particular interest to anyone who’s ever wondered what happens to farm chemicals once they’re in the soil.

“Here in the Midwest, we have lots of farming and fertilizer. We also have ground water runoff, so we’re seeing nitrates, nitrites, phosphates—all of those starting to build up in our water,” she said. Currently, filtering is the only way to remove these elements. But that’s not working, resulting in problems like the vast red algae bloom in Florida that’s endangered a wide range of marine life. A catalyst she’s exploring could one day break those substances down, using a simple chemical reaction to create cleaner and safer water.

While she’s breaking things down, Jenny Davis is working in the opposite direction. Davis has long been part of an extensive effort to document and revitalize a uniquely American language that was quickly losing its voice.

“I’ve always been very interested in language and culture,” explained Davis, who began studying linguistics during her undergraduate studies at Oklahoma State University. “I also started to think about what might be happening with my own community, the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma.” According to Davis, all indigenous languages in the U.S. are endangered, and some have even gone dormant with no living first-language speakers. Chickasaw was on that path.

When Davis began working with the Chickasaw Nation as part of a summer internship back in 2007, there were only about 100 first- language speakers and very few resources, including one dictionary and a book that was originally released with cassette tapes back in the 1980s. Today, it’s a very different story. The nation now has its own independent language department, which offers university courses and immersion programs, as well as a speaker’s council with about 24 remaining speakers who provide translations and approve new words. That’s important, because to thrive, every living language needs to adapt. Recent additions include a word for “nerd,” the equivalent of “LOL,” and yes—there’s even a word for “light saber.” It’s all very exciting for Davis, who was fortunate to be there in the beginning, providing the analysis and ethnography essential in the language revitalization process.

Today, in addition to her professorial appointments she directs the Native American and Indigenous Languages Lab. Her work concentrates on contemporary indigenous languages and identity, and interprets how those in tribal lands and urban communities navigate those spaces and connect with their language, whether it’s face-to-face or using the latest phone app.

She’s also currently working with other U.S. and Canadian scholars to develop a training program that could help other communities learn how to do language documentation and revitalization. Ultimately, she hopes that the skills now siloed away in academic spaces can be redistributed to local communities where they can take on a life of their own. “If I do my job right, I’ll be completely obsolete,” Davis said.

Language, like any other skill, requires a high degree of thinking. That’s the domain of Dan Hyde, who’s exploring cognitive development in young children. “In my research, I try to understand how humans come to understand abstract concepts,” explained Hyde. “The majority of my work focuses on how people develop concepts of numbers and mathematics.”

According to Hyde, a recent study of preschool-aged children showed that their understanding of objects was related to their understanding of number words. “The nature of the brain response suggested that differences arose in how attention was distributed to the objects,” said Hyde, who found that children who had a better understanding of number words distributed attention to objects more effectively than others. Because preschool numerical abilities are a strong predictor of mathematical achievements in elementary school, his work could eventually help parents and educators prepare young children to excel in math.

It’s not the first time Hyde has explored the cognitive functions in children. In an earlier study he focused on the “theory of mind,” which is essentially our ability to assess the thoughts and beliefs of others. Previously, many researchers thought that very young children could not grasp these concepts until they were old enough to verbalize them. But using a new technology called near-infrared spectroscopy that measures how light scatters on the surface of the brain, Hyde was able to show that infants as young as 7 months might be able to distinguish when others hold true and false beliefs.

Today, it’s far too early to tell where all of the work by Hyde and the others will lead. Studies need to be verified. Trials need to be completed. In some cases, the models that govern the way things have “always been done” may have to be rethought or thrown away. But that’s how progress is made. One question. One leap. One bridge at a time. At Illinois, those bridges are being built by an amazing group of young professors who are constantly expanding our horizons. And only time will tell where their impressive spans may lead.

Editors's note: This story originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of LAS News magazine.