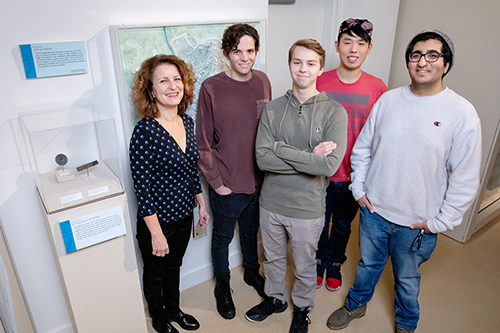

Classics professor Angeliki Tzanetou and her students explored issues of war and trauma through Greek tragedies and learned how the themes presented in the ancient dramas are connected to present-day crises.

Tzanetou taught “The Aftermath of War in Greek Tragedy” for the first time this fall semester.

“The reason tragedy survives, its timelessness, is rooted in the fact that it spoke to real political and moral issues people were grappling with. It has the power to connect with contemporary issues,” Tzanetou said.

The Athenian playwrights wrote stories of the Trojan War and the audience for the tragedies performed at the ancient theater of Dionysus in Athens would have been mostly male. Many of them would have been veterans of war, Tzanetou said.

“They would sit together as a community. There’s some emotional cleansing that goes on,” she said.

The class studied themes that include combat trauma and what happens when war veterans return home after being absent from their families; displacement, migration, refugees and asylum; and the trafficking of women and sexual violence.

The students read ancient Greek tragedies and also contemporary works, including psychiatrist Jonathan Shay’s books that connect post-traumatic stress disorder with war experiences described by Homer in the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey.” Several students said connecting the work of the ancient Greeks to problems in the world today made reading the plays more engaging.

They watched films such as “Queens of Syria” by Yasmin Fedda, based on Euripides’ “Trojan Women” and about Syrian women forced into exile; “Mojada” by Luis Alfaro, an adaptation of Euripides’ “Medea” to the Mexican border crisis; and “4.1 Miles” by Daphne Matziaraki, a documentary on Syrian refugees in the waters between Turkey and the island of Lesbos.

Sophomore Hamza Lodhia appreciated that the focus was not only on issues involving veterans but also on others who are affected by war in different ways. He was particularly moved by “4.1 Miles.”

“It gave a visual representation of a real problem going on. It’s not just veterans but people impacted by war,” Lodhia said.

The students also spent several class periods at the University YMCA’s New American Welcome Center, which provides resources to new immigrants.

“It helped me become aware of a community that I didn’t even know about. In class, professors will tell us how the class relates to real-life situations, but rarely do teachers tell us what we can do about an issue,” said sophomore Vincent Kim.

The students’ final project was to stage a reading that adapted a scene from a Greek tragedy to address a contemporary situation. A group of students including Kim, Lodhia, senior Oscar Serlin and freshman Max Serlin adapted the third play of the “Oresteia” trilogy by Aeschylus, in which Orestes is on trial for matricide. It illustrates the progress from exacting justice through bloody vendettas to replacing that with the rule of law.

The students reimagined the trial scene with Orestes as an American soldier in the Vietnam War being court-martialed for killing two other soldiers who committed atrocities during the My Lai Massacre. The themes they wanted to emphasize were the idea of justice being served, no matter the cost, and the ties of brotherhood and kinship.

“We were exploring the theme of someone doing something bad because he believed he was making up for something, and also his self-doubt, because no matter what (another soldier) did, they were still brothers in arms and that doesn’t go away,” Oscar Serlin said.

“In the play, Orestes is acquitted and not punished. We decided to update it so Orestes is punished in the end,” Max Serlin said. “The values in ancient Greece were much different – help your friends, hurt your enemies.”

Tzanetou said the group’s adaptation was outstanding in terms of its depth and sophistication.

“They didn’t just find a corresponding story, they thought very deeply about the themes,” she said.

The group is reworking the adaptation to add dialogue and make the court-martial scene more thorough, as well as increasing the elements related to kinship among the soldiers. Tzanetou plans to publish the adaptation in the journal Illinois Classical Studies, which is produced by the Department of Classics and published by the University of Illinois Press.

Other adaptations by students in the class used “Trojan Women” to explore the persecution of the Rohingya people in Myanmar and the fate of women living under Taliban rule in Afghanistan, and “Hecuba,” also by Euripides, to look at the oppression of women during the Bosnian war.

“One doesn’t have to have lived through war trauma or displacement trauma to feel these things,” Tzanetou said. “These things really touched the students, and it came out through their performances. It opens you up to be a better listener to other people, and it makes you feel at home with Greek tragedy.”

Tzanetou ended the class on a lighter note, with a study of Aristophanes’ comedy “Lysistrata,” about Greek women uniting for a sex strike in order to put an end to war.