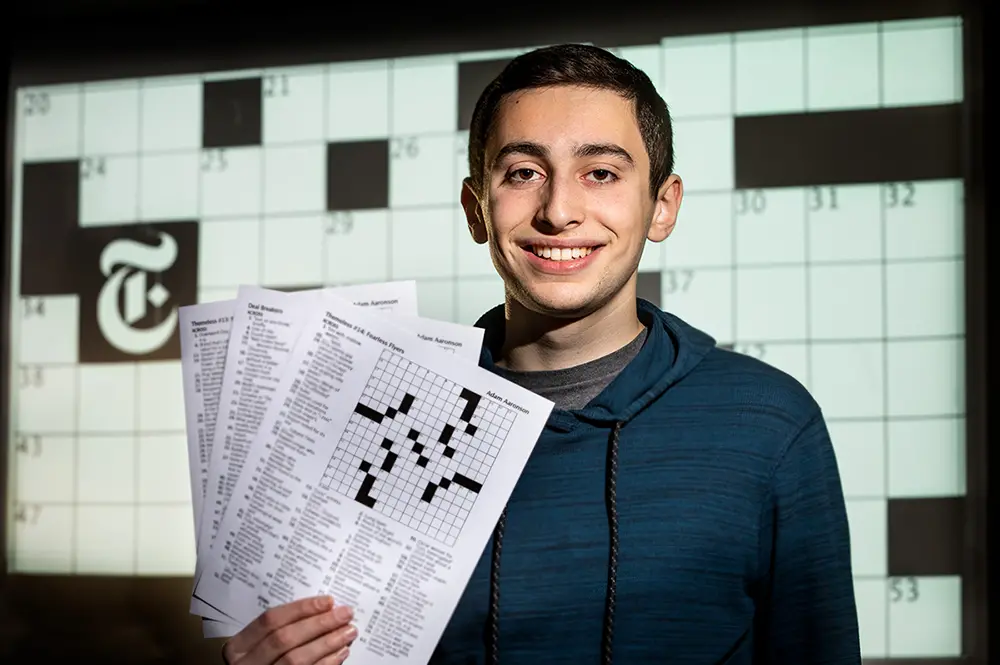

What's one way to pass time during the COVID-19 pandemic? You can do crossword puzzles, or you can make them, as is the case with University of Illinois freshman Adam Aaronson.

Aaronson is using the crossword puzzle-making skills that got him published in two of the country’s leading newspapers to keep himself occupied during the coronavirus pandemic.

“Social distancing has definitely given me ample time to work on crosswords," he said. "It’s a great pastime to have, especially in a time when so many people are all cooped up and bored.”

Being at home has also given Aaronson the opportunity to work with other crossword puzzle constructors over the internet. Aaronson, who is from Deerfield, Illinois, regularly makes puzzles and submits them to various publications including The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, two papers that have already published his work.

The computer science major and pending linguistics minor (he'll officially make it a minor in the fall) said that he collaborated with a friend from high school on their puzzle that was published in the Wall Street Journal on Feb. 3. His puzzle that was published in the New York Times ran on January 4, which was a Saturday, the day the publication runs its most challenging crosswords.

“When my New York Times puzzle got published, it was exciting to be at the receiving end of the giant wave of comments, reviews, tweets, and blog posts about my crossword. There is a huge community of passionate crossword solvers all across the internet, and it was surreal knowing that they all solved my puzzle.”

Though he states that he can’t reveal too much information about his potential impending puzzles, one of his favorite clues is “How to mend a broken heart.” The answer? CPR.

Aaronson has only been making crossword puzzles for a year. He received about a dozen rejections from the New York Times before getting an email last December telling him the newspaper had accepted one of his puzzles.

“Creating a crossword is a puzzle in itself – what combination of words fit together, where to put the black squares. You have to include words that will be interesting to the people who are doing it,” Aaronson said. “There are some tricky words and tricky clues throughout. There are some long words you have to piece together and figure out as you’re solving it.”

The puzzle editors told him in an acceptance email that they would publish his crossword puzzle quickly because it is his first puzzle to appear in the paper and because he is young. They praised the 18-year-old’s work and the interesting longer words he used in the puzzle.

"We could tell you had real constructing talent from the get-go,” the editors’ email to Aaronson reads, in part. “Really stellar work; we hope you're just getting started.”

Aaronson started with a particular word he wanted to include in the puzzle and positioned it in the grid first.

“I have an ongoing list of words that I think will be fun and interesting to include in a crossword that have never been in The New York Times crossword before. I often pull from that list and build a grid around it,” he said.

He can search for words in an online database for The New York Times crossword puzzles and see if they’ve appeared before in the paper’s puzzles.

“I’ve been interested in puzzles in general for my whole life – jigsaws, word puzzles, logic puzzles. I would make word searches and mazes for friends,” Aaronson said. As he got older, he began making trivia quizzes on the Sporcle website. “Crosswords were a natural progression of my interest in puzzles and words and trivia.”

The first crossword puzzles he created took him more than two months to complete. He created them manually and used some websites to help in searching for words. He’s become more efficient in making the puzzles, and it took him about a week this summer to create the puzzle that will be published.

“Once you get a spark of inspiration, it gets a lot faster and you can zoom through the creation process,” he said.

The most time-consuming aspect, taking a lot of trial and error, is placing the words in the grids. Creating the clues is straightforward, he said.

Aaronson uses a software program called CrossFire that suggests how to place certain words and indicates if a certain combination of words will be impossible to fill into the puzzle.

“A puzzle should have a lot of fresh, lively vocabulary. The quality of it is determined by how interesting the words are,” he said.

When he received rejections for other puzzles he’s submitted to The New York Times, the rejection emails included feedback and constructive criticism.

“When I first started doing it, it seemed like a super daunting process. There are so many empty squares you have to fill,” Aaronson said. “But there are a lot of resources online on how to make crosswords, so it’s really accessible. It’s really addicting, too. Once you get started on a grid, you really want to finish it.”

“It’s a really fun process, and since I’m interested in logical thinking and also creativity, it’s the perfect intersection of those,” he said. “It’s an awesome hobby.”