Public monuments are built to represent an idea—and this year, in particular, the ideas of the past have been put under the microscope.

Following the killing of George Floyd, protesters in the United States and around the world have toppled or defaced many statues of controversial historical figures whose thoughts and actions were harmful to Black and Indigenous populations. Statues of Jefferson Davis, Christopher Columbus, Albert Pike, John Calhoun, and others have been defaced and toppled by angry protesters. Other monuments have been removed by government officials.

The response to the removal of public monuments has been mixed. While many believe the ideals those monuments represented were unacceptable, some think the monuments represented their community’s history and culture and should have been left to stand.

Why do these statues elicit such emotion? Anthropologist Elizabeth Sutton, director of the Spurlock Museum, believes that people are passionate about monuments as the original purpose behind them is to immortalize those who have positively impacted society.

“Community members believe these individuals have accomplished something great and deserve to be honored, remembered, and emulated,” said Sutton. “As long as they continue to be recalled by the living, these honorees never ‘die’ but instead continue to have a very real presence in the hearts and minds of community members.”

She pointed out the significance of monuments such as the Statue of Liberty or U of I’s beloved Alma Mater that, while they don’t represent real people from history, represent ideas or principles.

“They serve to demonstrate to outsiders what the community values and strives for,” said Sutton. “Additionally, they are a reminder to community members themselves to continue to work towards these ideals and uphold these values in their own lives.”

Marc Hertzman, professor of history, recently co-authored an article for Public Seminar in which he argues for the importance of a more diverse array of public monuments.

“On a very basic level, the monuments we build should, at minimum, at least approach something resembling historical accuracy,” Hertzman said. “Instead we (currently) have a landscape of monuments dominated by one group of historical actors—white men—many of whom did terrible things.”

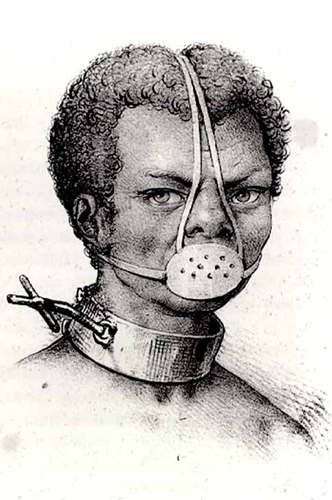

Hertzman’s article tells the story of a once enslaved woman of African descent named Anastácia, whose portrait first appeared as a representation of the horror of Brazilian slavery in the writings of French author Jacques Arago. Anastácia reportedly possessed great healing powers and performed several miracles. She died in captivity.

Anastácia’s legend is intertwined with that of Brazil’s Princess Isabel, who in 1888 signed the Golden Law which abolished slavery in the country. Decades after her death, Princess Isabel’s remains were placed on display in a museum in Rio de Janeiro for two weeks. The museum’s director placed a portrait of Anastácia in the museum at the same time to show the forms of torture that Princess Isabel helped end. Anastácia’s popularity rose even more, and she eventually became a folk hero and a symbol of resistance and strength in the South American country.

Hertzman believes erecting monuments of forgotten historical figures such as Anastácia will ultimately help societies become more equal and inclusive.

“I think that when we recognize, honor, and respect people who have been effectively erased from mainstream histories, we take at least a small step towards the larger goal my co-author and I express in the article—building a society that truly celebrates, honors, and respects living Black women,” Hertzmann said.

Sutton added that a lack of inclusivity in decision-making helped lead to the erecting of many of the most controversial monuments in the U.S. Though monuments are meant to represent the beliefs and values of an entire community, the decision to erect them is almost always made by a few people in influential positions, she said.

“Unfortunately, the reality is that many statues and monuments merely demonstrate the values and beliefs of these few who hold the power, instead of the values and beliefs of the community as a whole,” Sutton said.

The recent removal of several monuments provides the chance for communities to implement a more collaborative approach to choosing what monuments are built, Sutton said.

“As these statues come down, there is a tremendous opportunity for communities to reimagine these public spaces and develop more inclusive processes for deciding who should be remembered and what values they will work together to promote,” Sutton said.

Sutton also cautioned against adopting a stance of moral relativism when deciding which public monuments we should allow to be erected in our midst. Forgiving historical figures who carried out harmful ideas just because they lived a long time ago would be a mistake, she said.

“If we simply dismiss these actions [such as the transatlantic slave trade] as a product of another time,” she said, “we are refusing to acknowledge that these historic actions continue to have very real consequences in the present.”