Socialism has become a divisive word in American politics. Former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders brought its tenets into mainstream discussion, and polls indicate that younger Americans are becoming more open to the concept, but polls also indicate that older Americans remain staunchly opposed. Socialism, said history professor Maria Todorova, has become an “ideological boogeyman.”

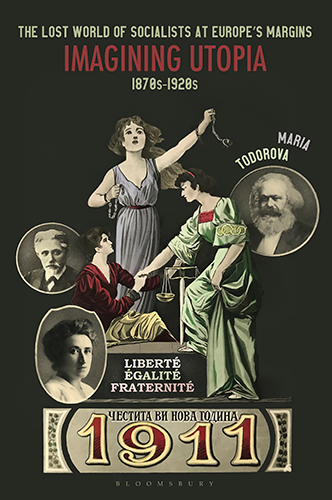

It’s also a topic with deep and revealing historical roots, and the professor explores the subject in her new book, “The Lost World of Socialists at Europe’s Margins: Imagining Utopia, 1870s-1920s,” where she examines the lives of early socialists.

The book idea came about while Todorova, Gutgsell Professor of History, was working on research about memories of communism in post-communist periods. She discovered an unused collection of around 4,000 documents at the Central State Archives in Sofia, Bulgaria, which were classified as the “memoir documents” of early socialists. They included memoirs produced between the 1930s and 1980s, handwritten diaries dating from the early 1900s, and personal correspondence from as early as the 1870s.

Todorova initially researched these records out of curiosity, but her findings grew until finally she decided to write a book about it. During her research, Todorova said she began to develop questions about the records: Who were these people? How were they educated? Why were they attracted to Marxist socialism, and what happened to them?

In an attempt to reconstruct the lives of these early socialists, she examined hundreds of sources, including biographical dictionaries, encyclopedias, biographies, published institutional and private sources, published and unpublished memoirs, historical monographs, museum card and photo-catalogues and archival materials. With her gathered information, she created a database of comparable data, leading to the digitization of close to 3,500 individuals.

“The history of the gathering of this archive is in itself a fascinating story, ranging from donations to purchased acquisitions to commissioned pieces,” she said. “It thus aptly highlights the intersection between official and personal memory. This enormously rich source had never been tapped and for all practical purposes neglected and underestimated.”

Todorova said her book is an emancipatory project about socialism at large, but focuses on the lives of early socialists. The term socialism generally applies to a belief in collective or democratically elected government, public ownership of certain items and services, and social justice but it’s considered a less rigid ideology than communism.

The socialists discussed in Todorova’s book include Marxists, anarchists, anarcho-liberals, populists, left-wing agrarians, left-wing members of different nationalist organizations, as well as the “invisible” women who supported socialist movement. She dedicates the book to her grandparents, who were a part of the generation and whose lives are also made apparent within its pages.

The book consists of are three parts. The first offers a “big picture” of socialism’s golden age, from the 1870s to the 1920s, when the social-democratic movement was at its peak. The second goes into depth about the “intersection or interplay of several generations of leftists.”

The third part focuses on individual experience, as it investigates the intersection between subjectivity and memory as reflected in written sources, such as published and unpublished memoirs, diaries, personal correspondence, biographies and autobiographies, and records of oral interviews. Todorova said these records allow for the reconstruction of the first socialist generations.

Todorova said that while many Americans are distrustful of socialism, it is no longer a bad word for an increasingly large population. She points out, however, that she didn’t write the book to make an impression or impact in the current American political landscape. Todorova said the book seeks to illustrate the lives of those who pursued the socialist ideology and the utopia implicit in it.

“It goes back to the experience of people who thought and dreamt of utopia and struggled to achieve it,” Todorova said. “It does not matter how they called their dreams – ‘liberty,’ ‘equality,’ ‘fraternity,’ ‘justice,’ ‘happiness,’ ‘hope,’ ‘revolution,’ ‘socialism,’ ‘communism,’ social democracy’– the important thing is that they were involved in a movement which worked toward their idea.”

For more stories about politics and politics-related issues, visit the Politics and LAS page.