This past May, Abbigail Bugenske became one of the country’s latest million-dollar winners. But she didn’t get it from a scratch-off; she got it for taking a gamble on hope. Bugenske was the first winner in Ohio’s “Vaxx-a-Million” sweepstakes, a five-week contest designed to get more state residents to take a COVID-19 vaccine shot. From cash lotteries to free beer and amusement park tickets, the unvaccinated have been offered an ever-growing raft of incentives in a national push to reach herd immunity. But the question still remains — will new incentives be enough to overcome resistance that’s as old as vaccines themselves?

When British physician Edward Jenner first pioneered a vaccine for smallpox in 1796, there were those who voiced concerns. In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, historian David Motadel said clerics argued that Jenner’s methods, which used exposure to the much milder cowpox virus to inoculate recipients against smallpox, contaminated the human body with animal matter and were therefore “unchristian.” There were also fears that children who received the treatment could develop distinctly bovine features.

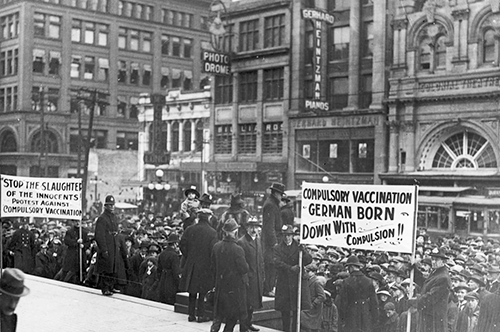

Fears aside, the vaccinations worked, leading countries like Great Britain to pass laws making them compulsory for children. That move, however, led to another fear that echoes in today’s battle over vaccine passports — that an obtrusive government was overstepping its bounds.

Those who opposed vaccines had reason to be concerned. Vaccinations were much cruder than they are today and could lead to secondary infections. Some vaccinated children even died of blood poisoning, causing many to argue that compulsory vaccinations were a violation of their basic autonomy.

Protestors marched in the streets, carrying children’s coffins and effigies of Jenner. They also organized—creating leagues such as the Anti-Vaccination Society of America that lasted clear into the 1910s. Gradually, however, vaccines gained more acceptance, aided by the success of the polio vaccine, which eliminated a major health threat in the United States.

Then came Andrew Wakefield.

In 1998, the British physician and 12 coauthors published a paper in the Lancet, linking the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine with autism and colitis in children. Eventually, the discredited paper was retracted, and its author stripped of his medical license — but the damage was already done. Faith in vaccines was shaken. And the fears surrounding them would eventually move from distinguished medical journals to social media.

With the COVID-19 vaccines, those old fears took on a whole new life. There were stories that Bill Gates was using the shots to microchip vaccine recipients and that the mRNA in the shots could alter human DNA — much like the bovine fears of the past. The fears have been addressed or debunked by experts, but they live on, adapting and mutating much like the virus itself.

In 2020, Dolores Albarracín, a former professor of psychology, business, and medicine at U of I, co-authored a study exploring social media’s influences on anti-vaccine sentiment during the 2018-2019 flu season. “When we began, there were hints that people who oppose vaccines hang out in certain online groups,” said Albarracín. “But the two phenomena of opposing vaccines and certain other activity were observed at the same time, so we didn’t know which came first. Do people who oppose vaccines seek groups that oppose vaccination, or do people who join these groups by accident later learn to oppose vaccines?”

The study, which observed the tweets of more than 3,000 Americans, included surveys that questioned participants about their opinion of vaccines, their vaccination history and whether they discussed vaccinations with others. More than 115,000 tweets were also linked to the counties they came from so that researchers could get a better sense of what vaccine conversations were prevalent in the communities where they originated.

The study found that when fraud, “Big Pharma,” and children were part of Twitter discussions in November-February, there were fewer vaccinations in February-March and April-May. However, this association was absent when participants discussed vaccines with their family, friends, and physicians, indicating that real-world conversation can offset misinformation disseminated online.

“Most COVID vaccination fears are related to misinformation and conspiracy beliefs,” said Albarracín. Of course, they’re not all based on urban legend. When six recipients of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine developed a blood clotting disorder in early 2021, the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention temporarily halted distribution to investigate. The drug was eventually cleared again for public use, however the mere fact that it had been investigated was enough to raise concerns.

“The companies and the authorities did exactly what they’re supposed to do, which is stop the trial and investigate the incidents,” said Jessica Brinkworth, former biologic drug policy analyst and current professor of anthropology, who studies the evolution of human immune function. But in showing caution, they sowed it, prompting some to consider the drug unsafe.

“Clotting is a really important anti-microbial mechanism, not just because it keeps stuff out, but because it captures stuff in circulation,” explained Brinkworth. “If you’re infected with anything, you’re clotting at some scale, more in severe infections. So severe COVID-19 is associated with widespread clotting. Systemic clotting can be triggered by many other non-infectious conditions. In terms of whether it’s associated with the vaccine, so far, all of those investigations have suggested that it’s not the vaccine that’s in play or has even necessarily triggered it.”

Some vaccine fears are rooted less in the shots and more in in the systems behind them, added Brinkworth. Women often report incomplete medical exams, and undocumented workers fear that a trip to the clinic could lead to deportation. Studies have shown that in emergency departments and intensive care units African-Americans often receive pain medication and other medical aid later than their white counterparts. “Work in this area suggests a lot of these failures probably stem from unintentional or implicit bias, or misunderstandings about human biology and race,” said Brinkworth, “but the interaction with medical institutions regardless is negative and it creates disparities in patient well-being and survival.”

Perhaps the lure of million-dollar jackpots will be enough to convince some to overcome their hesitancy. Ultimately, the real gamble for those yet to get vaccinated is that the virus could continue to mutate, becoming more virulent and developing mechanisms that allow it to escape the vaccine. It’s that type of scenario that has led the World Health Organization to declare vaccine hesitancy one of the ten threats to global health.

The best solution, however, could be far less expensive than lotteries and giveaways. “Honestly, my experience with people who question vaccines is that it’s a long, on-going conversation,” said Brinkworth. “If you’re kind and you’re understanding, then you stand a chance of helping that person better understand the biological reality, assess that against their own fears, and see if that’s the right decision for them.” And the biological reality, she added, is that the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh the known risk of a virus that’s killed millions around the globe.

Editor's note: This story first appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of LAS News magazine