Tamara Chaplin’s journey to uncover untold stories about French women’s lives began with a challenging tale of her own. She was a professional ballet dancer in New York and Canada until age 30 when she was injured and could no longer perform. Having focused her entire life on dancing, suddenly her options were few.

“Dance was the only thing that I ever wanted to do with my life, but then I got hurt and I could no longer perform,” said Chaplin, now a history professor at U of I. “I had left high school (to dance) when I was 16, so suddenly there I was with no job, no driver’s license, I had never used a computer, and I barely had a high school education.”

She went back to school and completed an undergraduate degree in history at Concordia University in Montreal before attending Rutgers University, where she earned a doctoral degree in French history.

In 2002 she joined the U of I as a professor of Modern European history. Her first book was a history of the televising of philosophy in France. Her new work is influenced by her background as a dancer, with much of her research focusing on media and performance. More broadly, she studies and teaches the history of gender and sexuality, contemporary France, World War I, and human rights.

Her second book, “Becoming Lesbian: A Queer History of Modern France,” will be published in 2023 by The University of Chicago Press.

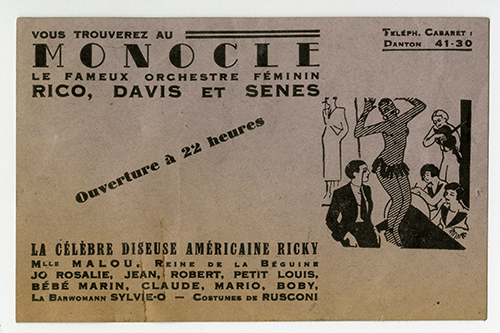

The book explores topics such as the 1930 Parisian Sapphic cabarets that featured the public performance of female same-sex desire; the relationship between sexual identity, sexual practices, and gender performance; how early TV brought queer female performances into living rooms throughout France and its empire in the 1950s and 1960s; and how an emergent feminist and lesbian rights movement used new technologies (from the Minitel—an early form of internet—to pirate radio, video, and film) to foster lesbian community and fight for social and political freedoms.

As her manuscript’s synopsis notes, the book “resists a widespread narrative of lesbian ‘invisibility, insignificance, unaccountability, and impossibility’ and attests to a French Sapphic presence that was observable, territorial, enduring, and often utopian in its collective expression.”

“One of the reasons I’m so fascinated by the parts of my work that focus on the cabarets and singers is because of my own history in the entertainment industry and television,” said Chaplin, in an interview with LAS. “It’s also a world where there are a lot of queer people—this has always been a part of my life and I’ve always been interested in non-normative forms of sexual and gender expression.”

The topic of women and gender performance in France was not easy for Chaplin to explore. The book is the result of 10 years of determined research that began in various French archives and, at first, led to dead ends. Of course, to Chaplin, as someone looking to write a new chapter of history, the lack of information wasn’t a deterrent.

“There are virtually no comprehensive histories of female homosexuality in modern France,” Chaplin said. “There are books about gay men and about women during specific decades, but there is as yet no history of lesbianism that covers the entire century. I thought ‘Great. Historians are always looking for things that nobody else has done.’”

It took Chaplin a long time, however, before she found information that gave her traction for her book. One feminist library said they had no information on lesbians, and the lesbian archive in the Women’s Center in Paris never seemed to be open.

Ultimately, she attended a conference held for the 40th anniversary of the feminist movement in 2010 in Angers, a small city in France. She hoped to meet women who could lead her in the right direction – and she did. She started interviewing people, learning more with each interaction and letting her findings lead to new ideas, archives, and primary sources. Several scholars told her that the police archives wouldn’t be helpful, but she went anyway.

“The things I found in the police archives blew me away. I totally didn’t anticipate finding them,” she said. The trail of discoveries led to more opportunities to meet people and learn more about this untold chapter in history.

“The opportunity to meet women, to talk to them about aspects of their lives that society has often rejected and to validate and legitimize what was so brave and important about their lives was a real gift for me and for those people,” Chaplin said. “It was often far more moving than you might anticipate.”

One woman shared graphic journals, which resembled comic books, describing her feelings toward other women. In a separate experience, Chaplin visited a 92-year-old woman, Liliane Robert, in a retirement home. Robert was a former cabaret performer, and at the end of the interview she sang and played the accordion for Chaplin, just as she had in the 1950s.

Now, more than a dozen years later, Chaplin has over 100 filmed interviews with women, thousands of photographed documents and journals on the history of lesbianism in France, and many photographs of collected memorabilia.

“One of the things that I want people who read the book to grasp is the knowledge that sexuality has a history, and that what we call ‘sexual orientation’ has always been far more fluid than we tend to think,” Chaplin explained. “People can be included in the public world regardless of any form of difference. I want people to see this part of the history of France as important not only to French history, but to the history of the West more broadly.”

Chaplin hopes to continue her research through a variety of projects. French producers have expressed interest in creating a television documentary using Chaplin’s filmed interviews and other research findings. She also hopes to create an archive of all the research material she has found so that it can be made accessible to other scholars and activists who may be interested in these sources. She is also considering publishing a collection of interviews, in order to produce a written record of these women’s voices.

In addition to her research, Chaplin teaches a variety of history classes and is active in the queer student community at the University of Illinois.

“I understand how important it is to have role models and to have people who are willing to come out publicly,” Chaplin said. “It doesn’t always feel safe. It’s a courageous thing to do.”