Craig Williams discovered his love of learning languages early in life. He began studying French in elementary school and, intrigued by the BBC series "I, Claudius," he signed up for Latin at his high school in Albany, New York. Eventually he earned his PhD in classical languages and literatures at Yale, and after 20 years on the faculty of Brooklyn College CUNY, he became a professor of classics at Illinois in 2013.

Having published several books including “Roman Homosexuality" and "Reading Roman Friendship,” Williams began to seek ways to make a perhaps surprising connection between his passion for the languages and literatures of ancient Greece and Rome and his own ancestry (Williams is of Mohawk descent). Coming to Illinois was a turning point.

Inspired by a conversation with Robert Warrior, director of the American Indian Studies Program at the time, Williams learned that the 1650 charter of Harvard College described its mission as “the education of the English and Indian youth.” Latin was the language of instruction at the college, Williams noted, "so there were American Indian students at Harvard who could read and write Latin, and some of their texts have survived.”

The earliest of these is a letter thanking benefactors in elaborate Latin, written in 1663 by Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk of the Wampanoag people, whose homeland is present-day southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. His letter was sent to London, where it was presented to King Charles II in 1664. Cheeshahteaumauk graduated the following year, and he was recently honored by Harvard with a newly commissioned portrait. His letter is housed in an archive in London, and Williams has been able to view it as well as manuscripts of two other Latin texts written by Native American students in 17th and 18th century New England.

Studying these texts led Williams to research the little-known history of Indigenous North American writers' broader connections with ancient Greece and Rome. He has recently published three articles on aspects of this history and its implications. Currently, Williams is writing a book that will bring together, for the first time, over 80 Native writers who have engaged with Greco-Roman antiquity in various ways from the 17th century to today.

In support of his research, Williams was awarded a Short-Term Whitney J. Oates Fellowship in the Humanities Council and Department of Classics at Princeton University last year. He has also received fellowships from the U of I Center for Advanced Study, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Germany), the Morphomata Center for Advanced Study at the University of Cologne (Germany), and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

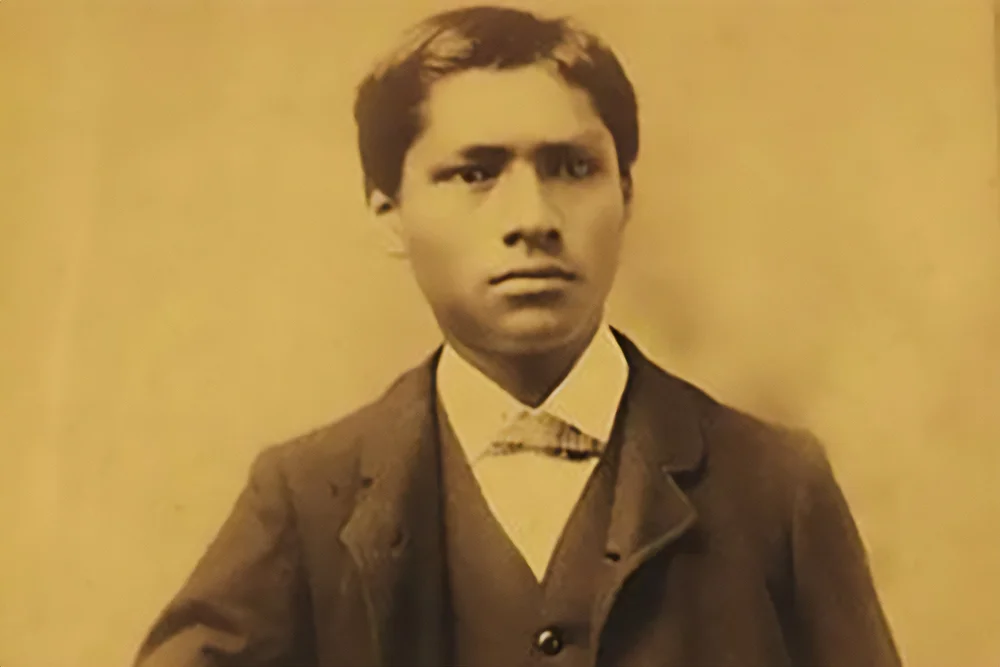

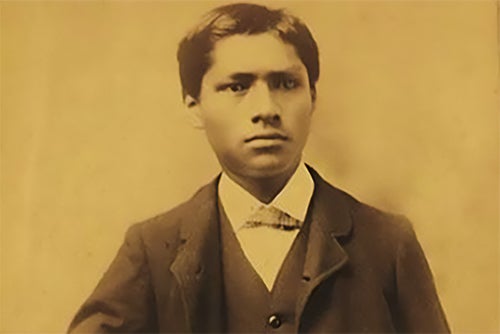

In the course of his research, Williams came across a U of I connection. Carlos Montezuma – also known by his Yavapai name, Wassaja – graduated from Illinois with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1884 and subsequently practiced medicine in Chicago; there is now a residence hall on campus named after him. Wassaja was a member of one of the university's literary societies, and at a speech contest in 1883 he spoke on the theme "the Indian's bravery." The text of his speech has not survived, but the Daily Illini newspaper reported on it the next day, calling it "the most vivid, pathetic, and beautiful picture ever painted in our Hall."

“The only other thing the article says about his speech is that he compared Indian people to the Greeks at Thermopylae,” said Williams, who noted that by referring to the famous battle of 480 BC at which a band of Greeks resisted an invasion by the Persians, Wassaja was implicitly commenting on the invasion of North America by Europeans.

In the history of Indigenous writers' engagements with Greco-Roman antiquity Williams sees a variety of responses to destructive narratives of Native people. Referring to the 2018 book “Why Indigenous Literatures Matter” by Cherokee citizen Daniel Heath Justice, he said: “One of the most destructive of stories that has been told over the past few centuries is that of Indigenous deficiency—what Native people lack, what their cultures lack in comparison to European and Euro-American cultures."

“There is this vague idea out there of the glory of Greece and the grandeur of Rome," Williams noted, "and there's still so much ignorance about Indigenous cultures, histories, and present-day realities.” Part of this ignorance has been a history of labeling Native people as “savage or primitive or barbarian,” he added.

“I hope my research will help correct the ignorance and push back against those damaging narratives,” Williams said.

Many of the Native authors who will feature in Williams' book do just that. Some 19th-century writers, for example, pointed out the irony in Americans of British or German descent describing American Indians as barbarian, since the Greeks and Romans, long portrayed in Euro-American culture as paragons of history, considered Britons and Germans to be barbarians.

More recently, in a 1987 essay Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (Dakota) quoted from one of her poems in which she compares her people to the ancient Etruscans, whose civilization flourished before Roman expansion across Italy: "Surrounded and absorbed, we tread like Etruscans / on the edge of useless law." Cook-Lynn used this image of the widely admired Roman legal system to comment on the experiences of Indigenous nations in the United States and its legal system.

Another text Williams has come across in his research is a 2013 essay by the Mohawk writer Doug George on the traditional governmental structures of his Iroquois people, which have long relied on the equally valued contributions of women and men. By contrast, George wrote, "the widely praised Greeks held two thirds of their people in a state of slavery and denied women the right to participate in the governmental process," and he provocatively added that "the Romans were simply barbarians with a higher command of technology."

Williams pointed out that as white settlers spread westward across North America over the 19th century, many came to believe that American Indians were a "vanishing race." The concept continues to have a negative impact today, he added: “I still hear students talk about Native people in the past, as if they don’t exist today.” Williams noted that this is changing, however, as more people become aware that the Indigenous peoples of this continent have not only played a crucial role in history but, despite the injustices and dispossessions of the past few centuries, they and their cultures continue to thrive.